National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013

The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPA RSD) was a commitment by the Australian, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australian, Western Australian and Northern Territory Governments to address local Indigenous disadvantage. The NPA RSD officially commenced on 27 January 2009 and expired on 30 June 2014.

The broad intent of the NPA RSD, together with other relevant Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreements, was to contribute to improved access, range and coordination of services, improved levels of governance and leadership, and increased economic and social participation in 29 priority locations.

The NPA RSD required that the agreement be reviewed prior to its completion. An evaluation of the NPA was undertaken in 2013 and comprised:

- in-depth research with 207 key stakeholders

- a survey and qualitative research with 726 community members

- a survey of 338 local service providers

- analysis of outcome data from administrative sources and Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Both the survey of local service providers and outcome data included an analysis of outcomes in other remote communities to establish whether any improvements were part of a broader trend.

The evaluation was guided by four key questions:

- Has access to and delivery of services improved?

- Has the capacity of communities and governments to engage with one another improved?

- Have there been changes in the RSD sites that contribute to the Closing the Gap objectives?

- What have we learned from the initiative that can inform remote service delivery, community capacity building, and place-based approaches?

The report's appendices can be accessed at National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013 Appendices.

© Commonwealth of Australia 2014

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication

Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to below as the Commonwealth).

Creative Commons licence

With the exception of the Coat of Arms, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence.

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode.

The Commonwealth’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording:

National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013

Source: Licensed from the Commonwealth of Australia under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence.

The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the content of this publication.

ISBN PDF 978-1-922098-26-9 Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013 (PDF)

Doc 978-1-922098-25-2 Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013 (Hardcopy)

Print 978-1-922098-27-6 Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013 (RTF)

Foreword

The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPA RSD) is a commitment by the Australian, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australian, Western Australian and Northern Territory Governments to address local Indigenous disadvantage. The NPA RSD officially commenced on 27 January 2009 and expires on 30 June 2014.

The broad intent of the NPA RSD, together with other relevant Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreements, is to contribute to improved access, range and coordination of services, improved levels of governance and leadership, and increased economic and social participation in 29 priority locations.

The NPA RSD requires that the agreement be reviewed prior to its completion. An Implementation Review was conducted in 2012 and an evaluation undertaken in 2013. This report provides the results of the evaluation. Given the diverse nature of the evaluation itself, the report has multiple elements and authors. Dr Michael Limerick was commissioned to write an overview that assesses and summarises all the various elements of the evaluation.

To capture a diversity of voices, the evaluation incorporated several qualitative and quantitative methods conducted by a number of specialists. Data collection was conducted in two stages, commencing with over 200 stakeholder interviews by O’Brien Rich Research Group, and a survey of 338 service providers overseen by Dr Judy Putt between March and May 2013, followed by a community research study by Colmar Brunton Social Research between September and November 2013. The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) collated crime data and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) collated and analysed health data.

Importantly, the community research study was designed to capture peoples’ lived experience of change and includes a survey of 726 residents in a sample of RSD communities. Local Indigenous people were employed and trained to assist in conducting this study which involved both a quantitative survey and qualitative data collection and analysis.

A range of data on social and economic outcomes were collated and analysed for the evaluation. In analysing these data an assessment was made as to whether any changes were unique to the RSD communities or whether they were part of a broader trend.

The evaluation was managed by the Evidence and Evaluation Branch, which was part of the former Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). Following recent machinery of government changes this branch is now part of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

To provide overall direction for the evaluation, an Evaluation Advisory Group (EAG) was formed. The EAG comprised representatives from the Australian Government, state/territory governments, an Indigenous organisation and the former Office of the Coordinator General for Remote Indigenous Services. An existing Inter-Department Committee also provided data, advice and information to inform the evaluation.

Four key evaluation questions guided the evaluation:

- Has access to and delivery of services improved?

- Has the capacity of communities and governments to engage with one another improved?

- Have there been changes in the RSD sites that contribute to the Closing the Gap objectives?

- What have we learned from the initiative that can inform remote service delivery, community capacity building, and place-based approaches?

The evidence and findings are presented under the following chapter structure:

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1 - Evaluation overview, Dr Michael Limerick

- Chapter 2 - Introduction, Evidence and Evaluation Branch

- Chapter 3 - Progress in implementing the NPA RSD, compiled by Evidence and Evaluation Branch

- Chapter 4 - Community research study, Colmar Brunton Social Research

- Chapter 5 - Stakeholder interviews, O’Brien Rich Research Group

- Chapter 6 - Survey of local service providers, Dr Judy Putt

- Chapter 7 - Outcomes was compiled by the Evidence and Evaluation Branch incorporating crime data analysis by AIC and health data analysis by AIHW.

The executive summary provides high-level findings specific to the key evaluation questions. The evaluation overview provides a more detailed summary of these findings and places them in context with the existing evidence base. Chapters 2 and 3 provide factual information about the NPA RSD.

To reflect the government arrangements during the period covered by the evaluation, this report refers to the agencies prior to the change of government in September 2013. The lead Australian Government agency for the NPA RSD during this period was the former Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). Along with the states and the Northern Territory, other Australian government agencies, particularly the former Departments of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and Health and Ageing (DoHA) provided support and services to the priority locations.

The Australian Government would like to thank the New South Wales, Queensland, South Australian, Western Australian and Northern Territory Governments for their advice and provision of data and information throughout the evaluation process. The Australian Government would also like to thank the numerous people who participated in the research, particularly community members who provided an insight into their lives and communities, and the people who participated as researchers in the community research study.

Evidence and Evaluation Branch

Contents

Dr Michael Limerick, Limerick & Associates

1.4.Introduction to the evaluation

1.6.National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery

Evidence and Evaluation Branch

2.2.Background to coordinated service delivery to overcome Indigenous disadvantage

2.3.Remote Service Delivery Approach

2.5.Funding of the NPA RSD and IRSD Special Account

2.6.Relationship between RSD and related initiatives

3 Progress in implementing the NPA RSD

Compiled by Evidence and Evaluation Branch

3.4.Key achievements in RSD locations

Colmar Brunton Social Research

4.1.Highlights of study findings

4.4.Community knowledge of the Remote Service Delivery model

4.5.Perceptions of community leadership and community behaviour

4.6.Research findings against the evaluation questions

4.7.Perceptions of change in the community and quality of life at the community and individual level

4.8.Relationship between personal circumstance and survey responses

5.1.Background to key stakeholder interviews

5.5.Improving service coordination

5.6.Enhancing infrastructure and services

5.8.Strengthening community governance and leadership

6 Survey of local service providers

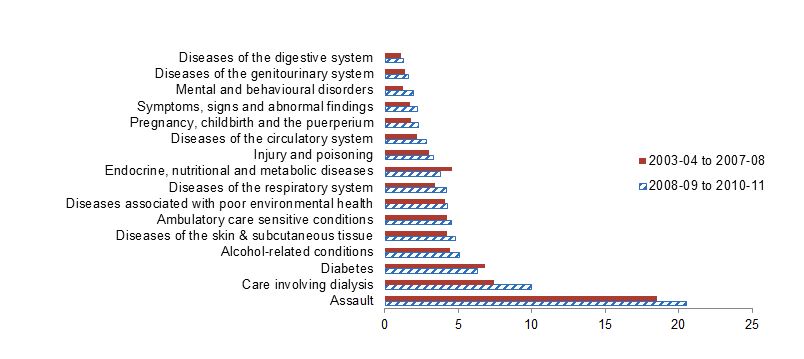

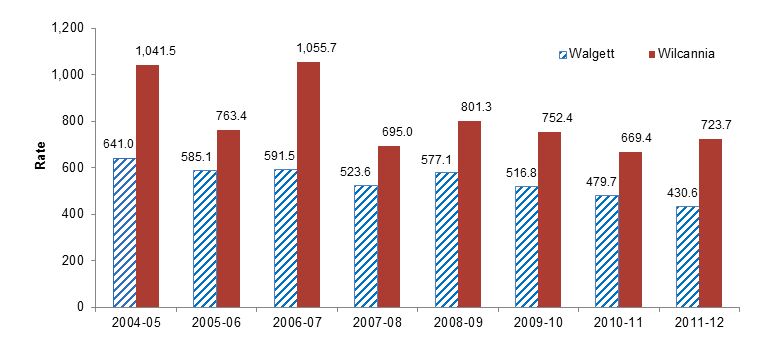

7.4.Health and community services

Abbreviations and acronyms

ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics

AACAP Army Aboriginal Community Assistance Program

APY Lands Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands

BER Building the Education Revolution

BOM Board of Management

CDEP Community Development Employment Projects

CGRIS Coordinator General for Remote Indigenous Services

CtG IHO NPA Closing the Gap in Indigenous Health Outcomes National Partnership Agreement

CtG NT NPA Closing the Gap in the Northern Territory National Partnership Agreement

COAG Council of Australian Governments

CYWR Cape York Welfare Reform

DEEWR Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

DoHA Department of Health and Ageing

EAG Evaluation Advisory Group

FaHCSIA Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

GBM Government Business Managers

GCO Government Coordinator Officers (Cape York Communities, Qld)

GEC Government Engagement Coordinators (NT)

GECO Government Engagement and Coordination Officers (Gulf Communities, Qld)

HOIL Home Ownership on Indigenous Land

ICC Indigenous Coordination Centre

IDC Inter-departmental Committee

IECD NPA Indigenous Early Childhood Development National Partnership Agreement

IEO Indigenous Engagement Officer

IRSD Indigenous Remote Service Delivery

IRSD SA Indigenous Remote Service Delivery (Special Account)

IPSS Indigenous Parenting Support Services

LAC Local Area Coordinator (WA)

LCAP Local Community Awareness Program

LIP Local Implementation Plan

LRG Local Reference Group

LSSSC NPA Low Socio-economic Status School Communities National Partnership Agreement

MES Municipal and Essential Services

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

NAPLAN National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy

NIRA National Indigenous Reform Agreement

NPA National Partnership Agreement

NPA DER National Partnership Agreement on the Digital Education Revolution

NPARIH National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing

NPA RSD National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery

NSW New South Wales

NT Northern Territory

NTER Northern Territory Emergency Response

ORIC Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations

PM&C Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Qld Queensland

RJCP Remote Jobs and Communities Program

ROC Regional Operations Centre

RPA Regional Partnership Agreement

RSD Remote Service Delivery

RSDC Remote Service Delivery Coordinator (NSW)

SA South Australia

SFNT Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory

SGI Single Government Interface

SLA Statistical Local Areas

SRA Shared Responsibility Agreement

TTC Trade Training Centre

WA Western Australia

Executive summary

Evidence and Evaluation Branch

The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPA RSD) evaluation involved a mixed-method approach with a focus on key components of the NPA RSD outcomes. Undertaken primarily in 2013, the evaluation comprised:

- in-depth research with 207 key stakeholders

- a survey and qualitative research with 726 community members

- a survey of 338 local service providers

- analysis of outcome data from administrative sources and Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

Both the survey of local service providers and outcome data included an analysis of outcomes in other remote communities to establish whether any improvements are part of a broader trend.

Findings

Service delivery

- There is strong evidence that the NPA RSD led to an increase in service provision in NPA RSD communities such as new houses, Children and Family Centres, youth services and social services particularly for families.

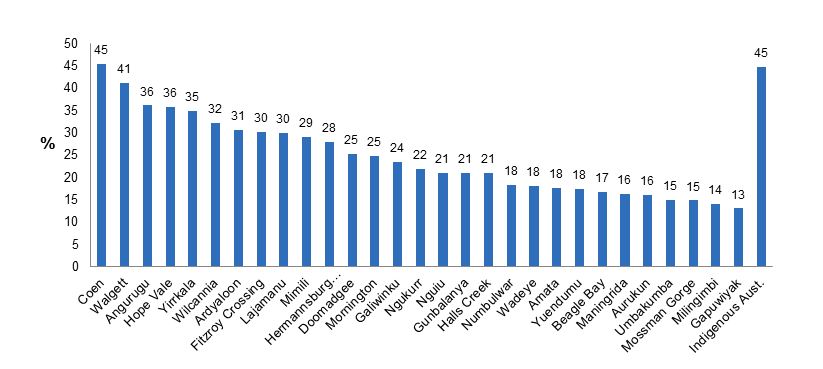

- The service provider survey showed that a statistically significantly higher proportion of local service providers in RSD communities (43%) reported that services had increased in the previous three years than service providers who worked in non-RSD communities (28%). However, there was less evidence of a significant and fundamental change in service practice and delivery.

- Community members recognised that there are more services available and considered key services to be more helpful. Community members identified that the challenge is now around encouraging people to take advantage of these opportunities and to use the new or improved services to help themselves and the community.

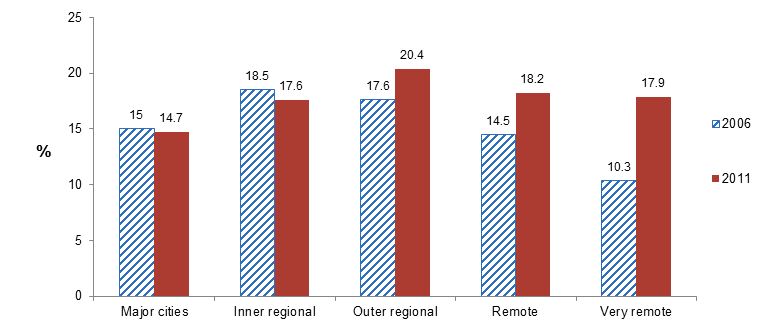

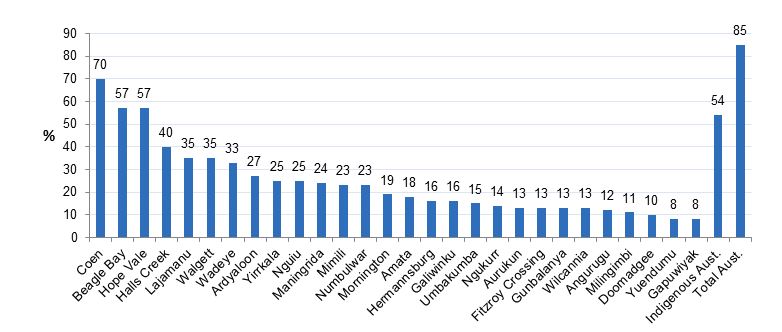

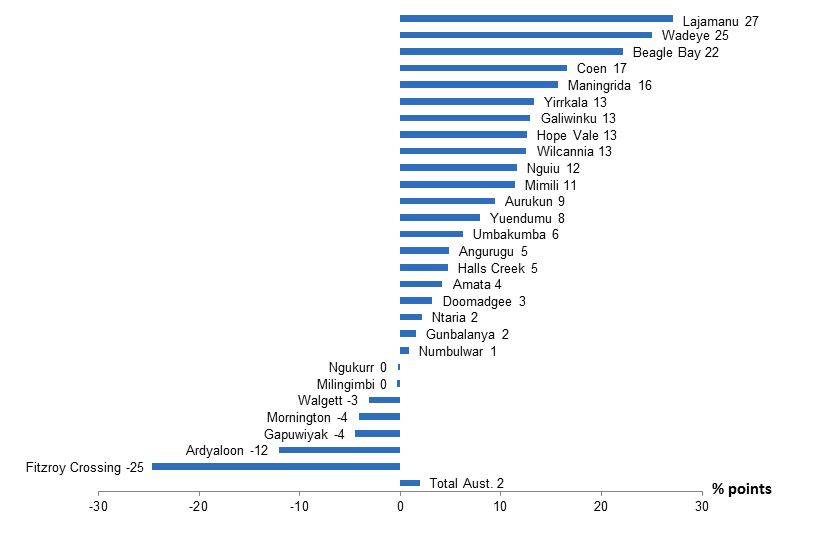

- Indigenous overcrowding rates in RSD communities fell at a considerably faster rate from 2006 to 2011 than for very remote areas in general. This reflects the fact that RSD communities were given priority under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH).

- There were mixed views on service coordination with some stakeholders and service providers suggesting that, in some instances, additional services had made the coordination task more challenging.

- Overall, 69 per cent of service providers reported that the NPA RSD was beneficial for the community.[1]

Coordination, engagement and capacity

- The majority of service providers were positive about the effectiveness of Government Business Managers (GBMs) – 66 per cent and Regional Operation Centres (ROCs) – 59 per cent in helping to coordinate service delivery.[2]

- There is strong support for – GBMs and Indigenous Engagement Officers (IEOs). Sixty-nine per cent of service providers believed that GBM positions were effective in helping community engagement while 68 per cent reported that IEOs were effective in assisting community engagement.[3]

- There were statistically significant differences in local service providers’ views of the NPA RSD, with those in Western Australia (78%) and Queensland (70%)[4] more likely than those in the Northern Territory (62%) and New South Wales (53%) to say the RSD was beneficial.

- The idea of Local Implementation Plans (LIPs) received good support; however in practice the experience was mixed. Around 70 per cent of service providers reported that LIPs were effective in identifying community priorities. However, lower proportions reported that LIPs were effective in generating change (34%) and increasing accountability (40%).[5]

- It was noted in previous reviews of the NPA RSD that LIPs were overly complex with a total of almost 4,000 actions initially identified.

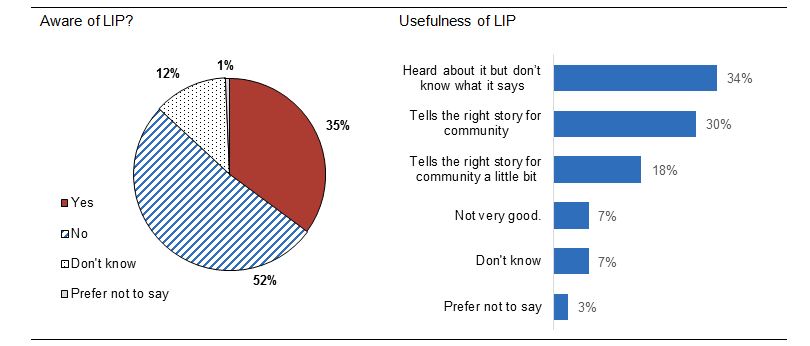

- Awareness of LIPs was limited among community members, and although there was support for having local plans among stakeholders and local service providers, the way in which the LIPs were developed and used fell short of expectations. Of the 35 per cent of community members surveyed in the community research study who knew of the LIP, 48 per cent thought that, to some extent, it told the right story for the community.

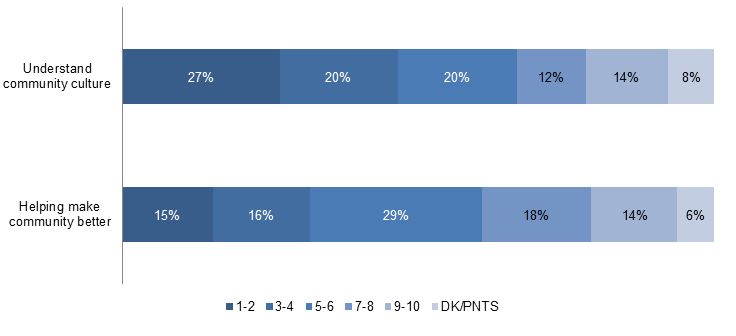

- In a survey of 726 community members, over half the respondents knew who the IEO was (54%) and 43 per cent knew about the GBM. In relation to government in its broader sense, when asked to rate the government out of ten, only a third gave a rating of ‘seven or higher’ in relation to the effectiveness of government in helping to make the community better. Just over a quarter rated the government ‘seven or more’ for understanding community culture.

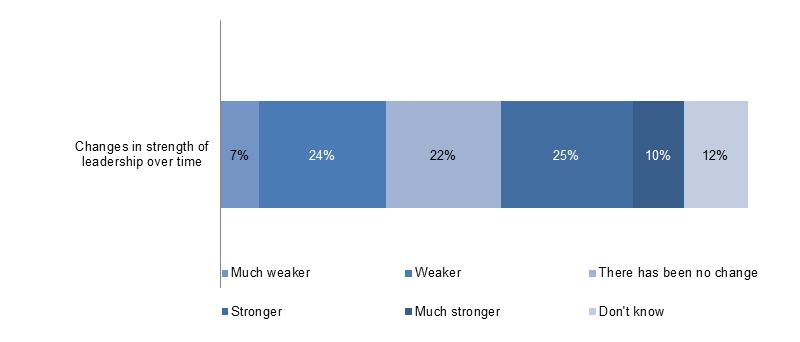

- The Local Reference Groups (LRGs) seemed to be well known with the majority of community members aware of its existence (61%). The community research survey shows relative positivity about the role of the LRG as a voice for the community and individuals (44% rated the LRG highly for talking up for the community and 37% rated them highly for talking up for the individual). However, the qualitative data indicates that this did not necessarily translate into community ownership or a feeling that the LRG was leading change or making services accountable. Critical factors that seemed to contribute to successful coordination and engagement included concerted support from the state/territory government, stable and strong leadership in government at a regional and local level and in local communities, and local commitment and resources to achieve the LIP goals.

- The objectives of the NPA RSD against which the least progress has been made are in building community capacity to engage with governments and building community governance and leadership capacity generally.

- There was a strong view amongst government stakeholders that the reporting requirements under the NPA RSD had been excessive and overly burdensome.

- Staff turnover within both government and community agencies was also reported as impacting on attempts to develop more locally-directed change or improvements. In the service provider survey, the majority of respondents (71%) said recruiting appropriately skilled or experienced staff was a ‘big’ issue for their service, while 58 per cent said staff retention was a ‘big’ issue.

Contribution to Closing the Gap

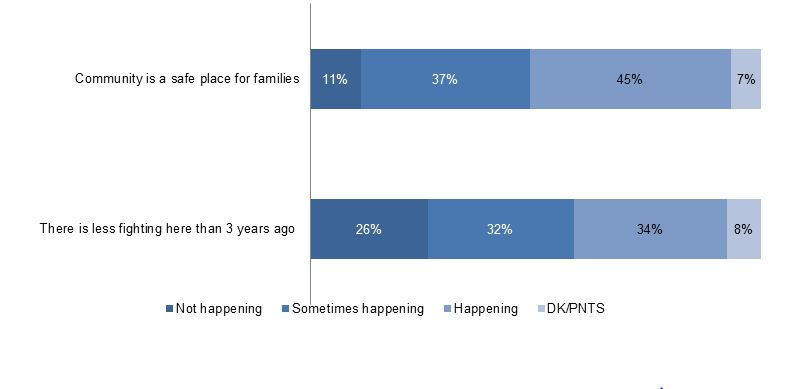

- Tangible gains did flow from the prioritisation of infrastructure and programme investment in the 29 RSD communities. Half of all community members surveyed considered that their community (50%) and their own lives (52%) were improving. Housing, infrastructure, early childhood education and employment were often cited as reasons why things were improving.

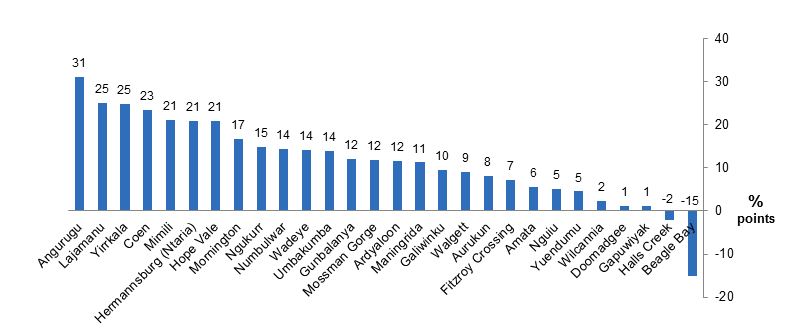

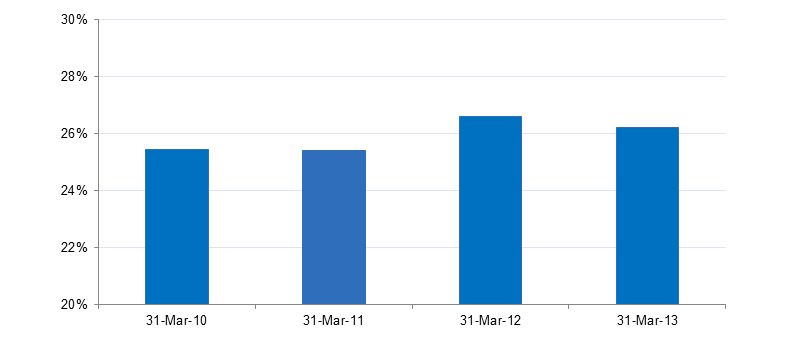

- While the outcome data showed some improvements in RSD communities this was generally part of a more general trend. For example, there were improvements in mainstream employment rates and year 12 attainment levels in almost all RSD communities from 2006 to 2011. However, with the exception of overcrowding, these improvements were part of a broader trend. In some instances, outcomes such as school attendance and National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) results have shown no statistically significant overall change across the RSD communities.

- Perceptions of local service providers indicated that to those on the ground there were limited achievements against Closing the Gap targets. This is not surprising as the NPA RSD has only had a limited amount of time to influence outcomes.

Lessons learned

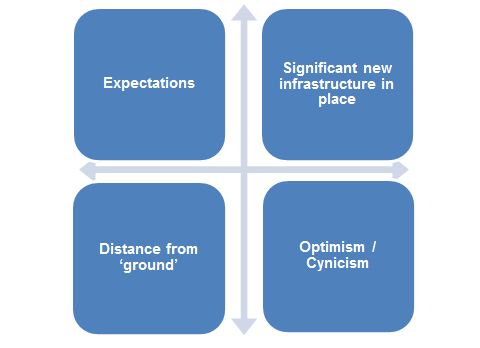

- There is a tension in the NPA RSD model between addressing service issues and community engagement. Future place-based initiatives should be mindful of this tension and be clear on where the balance lies. Pressure was brought to finalise LIPs quickly. This pressure may have affected community engagement. Partly reflecting the tension between these goals, stakeholders who thought that the NPA RSD was mostly about service equalisation were more positive about the NPA RSD than those that felt the NPA RSD was mostly about community development.

- The strong focus on getting the new government infrastructure and key NPA RSD coordination and engagement mechanisms in place seems to have overshadowed less concrete aspirations related to enhanced governance and leadership capacity within communities.

- The perception among some government stakeholders that the NPA RSD involved a heavy reporting burden may be related to the large number of LIP actions and the reports required by the NPA RSD. If a smaller number of action items were identified in local plans this may have reduced the reporting burden and allowed greater focus on key priorities.

- The NPA RSD has a focus on service coordination. While coordination can be beneficial, the evidence on the impact of improved service coordination is thin.[6] No credible evidence suggests that service coordination itself can bring about large improvements in outcomes. This does not mean that coordination should not be pursued but coordination alone may not bring about desired change.

- There was a view amongst many stakeholders that greater devolution of decision-making responsibility to regional and local levels would improve the ability of government to be responsive to community needs.

- The NPA RSD has clearly led to increased service provision in RSD communities over and above what would have happened in the absence of the NPA RSD. However, the impact of additional services depends on their effectiveness.

- Through the community research study, community members were asked in an open-ended question about the three most important changes needed to make their community a better place to live. The top responses were:

- a third (33%) of community members cited more jobs/relevant training

- just over a fifth (22%) mentioned more services and programmes with the same proportion (22%) specifying sport/recreation activities and services for youth

- just under a fifth (19%) mentioned more housing and housing repairs

- 17 per cent noted that kids need to be in school/education

- 17 per cent mentioned reducing the use of alcohol/drugs/kava with the same proportion mentioning improving roads/rubbish, sports facilities and infrastructure.

- The desire by community members for more employment comes out strongly. More generally, many of these responses go beyond service provision and relate to one of the objectives of the NPA RSD - ‘to increase economic and social participation wherever possible, and promote personal responsibility, engagement and behaviours consistent with positive social norms’.

- It is also worth noting that when it comes to service delivery the issues raised by community members in the community research study were similar to those raised in the baseline mapping reports, notably issues related to access roads and infrastructure.

1 Evaluation overview

Dr Michael Limerick, Limerick & Associates

1.1 Overview outline

This overview provides a summary and assessment of the evidence that was collected through the various elements of this evaluation. The overview also draws on the existing evidence base particularly in the section on lessons learned. More details on the individual elements of the evaluation are provided in other parts of the report.

The overview commences with an outline of the evaluation report, followed by a description of the evidence drawn on in this chapter to address the four evaluation questions. Section 1.4 provides an outline of the key questions and performance indicators that guided the evaluation. Section 1.5 provides contextual information that explains the origins and philosophy of the NPA RSD within the broader narrative of Indigenous policy. Section 1.6 provides a brief summary of the various elements of the NPA RSD and how they were intended to achieve objectives. Section 1.7, the findings, canvasses each of the key evaluation questions including the lessons learned and implications for future efforts to improve remote service delivery.

1.2 Report structure

The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery Evaluation 2013 report has been prepared by a number of authors, using a range of methodologies each focusing on one or more of the key evaluation questions.

- Chapter 1: Evaluation Overview, Dr Michael Limerick

- addresses the four evaluation questions drawing on a wide range of evidence

- Chapter 2: Introduction, Evidence and Evaluation Branch[7]

- provides a factual account of and background to the NPA RSD

- Chapter 3: Progress in Implementing the NPA RSD, Evidence and Evaluation Branch

- provides a factual account on the progress of implementing the outputs specified in the NPA RSD, as well as other key investments and achievements in the priority locations

- Chapter 4: Community Research Study, Colmar Brunton Social Research

- presents the results of a study designed to capture people’s lived experience of change and includes a survey of 726 residents and participatory qualitative research

- Chapter 5: Stakeholder Interviews, O’Brien Rich Research Group

- provides findings from over 200 interviews conducted with a range of stakeholders including Australian, State and Northern Territory government policy officers, Government Business Managers (GBMs) and Indigenous Engagement Officers (IEOs), local service providers and representatives of Indigenous peak bodies

- Chapter 6: Survey of Local Service Providers, Dr Judy Putt

- presents the results from an online survey of 338 service providers

- Chapter 7: Outcomes, Evidence and Evaluation Branch incorporating crime data analysis by AIC and health data analysis by AIHW.

1.3 Overview method

This chapter provides an overview of the Evaluation of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPA RSD). It summarises and synthesises the central themes and evidence to inform the key evaluation questions.

The chapter draws on evidence collected as part of the evaluation particularly:

- the community research study conducted by Colmar Brunton Social Research (Chapter 4)

- stakeholder interviews conducted by O’Brien Rich Research Group (Chapter 5)

- the service provider survey conducted by Dr Judy Putt (Chapter 6)

- analysis of outcome data (Chapter 7).

Additional material to inform this chapter is also drawn from:

- the six-monthly reports of the Coordinator General for Remote Indigenous Services (CGRIS)

- information on the CGRIS website, such as jurisdictional governance assessments

- Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) Audit Report No.43 2011–12 on the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery

- reports of the Northern Territory Coordinator General for Remote Services

- Implementing Remote Service Delivery- progress towards a new way of working with remote Indigenous communities to Close the Gap, 2013, FaHCSIA’s Implementation Review

- various reports produced as part of the NPA RSD initiative, including NPA RSD Annual Reports to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG)

- evaluations and reports into other initiatives that have touched on aspects of the NPA RSD implementation, including the review of coordination and engagement conducted for the Northern Territory Emergency Response evaluation and the Cape York Welfare Reform (CYWR) Evaluation 2012

- relevant program information about the implementation and outcomes of the NPA RSD initiative.

Academic and policy literature has also been used to position the evaluation findings in the broader context of current thinking about leading practices in service delivery to remote Indigenous communities.

1.4 Introduction to the evaluation

1.4.1 Key questions

This evaluation was conducted as a requirement of Paragraph 41 of the NPA RSD which stated that, ‘the Agreement will be reviewed prior to its completion in 2013-14, the final year of the Agreement, with regard to progress made by the Parties in respect of achieving the agreed outcomes’.

To measure progress in achieving the agreed outcomes, the evaluation is guided by four key questions:

- Has access to and delivery of services improved?

- Has the capacity of communities and governments to engage with one another improved?

- Have there been changes in the RSD sites that contribute to the Closing the Gap objectives?

- What have we learned from the initiative that can inform remote service delivery, community capacity building, and place-based approaches?

The questions were derived from the outcomes listed under Paragraph 16 of the NPA RSD that the Agreement will contribute to:

- standards of services and infrastructure to be comparable with non-Indigenous communities of similar size, location and need elsewhere in Australia;

- clear roles and responsibilities identified with all levels of government working together;

- community organisations deliver government services that meet relevant legislative requirements and are accountable to their constituents and funding bodies;

- improved access to services for Indigenous people in remote locations to support achievement of the COAG Targets. Ensuring:

- it is simpler to negotiate government services for Indigenous Australians;

- it is easier for Indigenous Australians to engage government services; and

- user-friendly services are provided to Indigenous Australians by government;

- better coordinated, consistent and connected government services and more highly developed capacity in Indigenous communities; and

- enhanced workforce planning including the development of local skills and a stable local workforce.

1.4.2 Performance indicators

Evaluating any place-based initiative is difficult as many factors can affect what happens in a particular place. Care is also required to measure the counterfactual – that is what would have happened in the absence of the specific policy or programme.

Evaluating the agreement was particularly difficult as it was not always clear what happened as a result of the NPA RSD itself. In a place-based initiative it is often possible to identify the additional services or programmes introduced as a result of the policy. To take the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), as an example, it was possible to identify additional police and night patrol services to each location.[8]

Identifying additional services provided under the NPA RSD[9] is difficult as many services were provided through other NPAs and some of these investments would probably have occurred in any case. Making this assessment is not straightforward. While the NPA RSD locations were meant to be given priority, it is not easy to establish that these locations would have received these additional services anyway. The Local Implementation Plans (LIPs) do not fully inform this assessment as they do not always articulate the additional investments. On the other hand it is clear that some additional services such as those provided through the Indigenous RSD Special Account[10] would not have occurred in the absence of the NPA RSD.

At one level it does not matter whether the additional services were provided as a result of the NPA RSD itself as the services were provided. An evaluation, however, needs to look beyond what was provided to attribute benefits to the policy itself. If the investments would have happened anyway then these investments cannot be claimed as a benefit of the NPA RSD.

Some complex implementation issues around things such as staff housing and land tenure also impacted on the extent to which broader RSD NPA outcomes were attained.[11]

Another challenge in evaluating the NPA RSD was the selection of performance indicators. Paragraph 23 of the NPA RSD states:

Under this proposal, performance benchmarks and indicators will differ from location to location. Performance indicators and benchmarks will be developed as part of the process of developing Local Implementation Plans.

While performance indicators were not developed as part of the LIP development process, the RSD Implementation Review[12] states ‘performance indicators for Local Implementation Plans in Northern Territory (NT) and Western Australia (WA) have been finalised and indicators for South Australia (SA), New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland (Qld) were due to be finalised’. As the indicators for SA, NSW and Qld had not been agreed at the time of the Implementation Review and the indicators for the NT and WA are high level indicators similar to those agreed by all jurisdictions through the performance management framework[13]; the outcome indicators used in this evaluation are consistent with those specified in the performance management framework.

If indicators had been developed as part of the LIP development process it would have been possible to measure each LIP against the key priorities in those LIPs. As this was not done, high level outcome indicators, aligned where possible, to the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Closing the Gap targets have been chosen. It is important to have realistic expectations about what changes might be discernable or attributable to the NPA RSD within the timeframe of the evaluation. Many of the high level indicators used for this evaluation change slowly. Health outcomes, for example, tend to change gradually. Also worth noting is that most of the LIPs were agreed in 2010 with some agreed in 2011. Given that much of the evaluation data refer to 2012 or earlier, if LIPs are taken as the starting point, the NPA RSD has only had a limited amount of time to influence outcomes. Despite this limitation, care has been taken to not only look at trends in outcomes in the RSD communities but to also make comparisons with other communities to assess whether changes are part of a broader trend.

The evaluation, therefore, did not just focus on outcome indicators as the impacts of the NPA RSD relate to measuring changes in the way government services are delivered and coordinated and the way in which governments and communities work together. Information on changes of this nature is best collected from service providers, government officials and community members themselves.

It is also important to have realistic expectations about what changes might be discernable or attributable to any service delivery initiative. As Stewart, Lohoar and Higgins[14] have noted there is only limited evidence to understand whether service delivery coordination leads to better outcomes either in Australia or internationally. There is no real evidence to suggest that service coordination itself will provide large benefits. The NPA RSD was not just about better coordination it also entailed the provision of additional services and involved a type of community planning which does not occur in all communities.

1.5 Historical context

To understand the scope and intent of the NPA RSD, it is important to consider governments’ evolving approaches to service delivery in remote Indigenous communities in recent decades. For much of the twentieth century, the majority of remote community services – municipal, essential and social – had been delivered by missionary or government administrations. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, the advent of self-determination policy led to the proliferation of Indigenous community organisations and representative councils, which assumed the funding and decision-making authority for the delivery of many local services.[15] [16] By the late 1990s, in most remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, local councils or community organisations delivered the majority of municipal and essential services, public housing, employment programs (e.g. Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP)), social programs (e.g. crime prevention, suicide prevention, alcohol rehabilitation, family support), sport and recreation, social security advice, banking and postal services (through agency arrangements), childcare, broadcasting, and land management. The only services primarily delivered by external agencies were schooling, health, and statutory services such as child protection and justice services. Even in these areas, many local councils and community organisations were involved in delivering primary health services, child protection, community corrections and even community policing and community courts.

By the early 2000s, it was clear that despite the reforms in remote Indigenous service delivery, limited progress was being made in overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. In fact, there were concerns that conditions in many communities were deteriorating.[17] There was an increasing focus on the governance and financial management deficiencies of many Indigenous councils and organisations as well as concerns about whether mainstream service standards were being achieved. There were concerns that Indigenous councils in remote areas were burdened with too wide an array of services, which was beyond their capacity to deliver.

At the same time, the administrative reforms associated with ‘New Public Management’[18] were filtering through to Indigenous affairs, with a shift to competitive tendering of service delivery, along with a focus on systematic measurement of outputs and outcomes. The dominant view was that the imperative for achieving mainstream standards of service delivery in remote Indigenous communities should be placed ahead of considerations of self-determination and community capacity-building. The pathway to overcoming Indigenous disadvantage was envisioned through services targeted at the gaps in Indigenous living standards and delivered to a higher standard under a strict framework of measurement and accountability for outcomes. Services and programs delivered by the original flagship for Indigenous self-determination, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Council (ATSIC), were progressively transferred to mainstream government agencies until the Commission was abolished in 2004. Delivery of services was put out to competitive tendering and contracts were increasingly entered into with larger non-Indigenous non-government organisations (NGOs) or private providers. This trend extended to programs with community development objectives, such as CDEP.

The new directions in Indigenous service delivery can be discerned in the various strategic reforms initiated by COAG through the past decade. In 2002, COAG commissioned the Productivity Commission’s Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage reports, published every two years containing key indicators intended to measure the impact of reforms to policy settings and service delivery. In 2004, COAG agreed to a National Framework of Principles for Delivering Services to Indigenous Australians, which emphasised sharing responsibility, harnessing the mainstream (including corporate, non-government and philanthropic sectors), streamlining service delivery, establishing transparency and accountability, developing a learning framework, and focusing on priority areas. By 2008, COAG had cemented the new outcomes-focused approach to Indigenous service delivery in the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, committing governments to six high level Closing the Gap targets across seven ‘building blocks’.[19] At the same time, COAG finalised National Partnership Agreements committing to significant new investments in services and infrastructure designed to close the gap on Indigenous disadvantage. New service delivery principles in the Agreement emphasised priority against the Closing the Gap targets, Indigenous engagement, sustainability, accessibility, integration between and within governments, and accountability. Specific principles for investment in remote locations emphasised achieving standards of services and infrastructure equivalent to comparable mainstream communities.

While the language of self-determination faded from government pronouncements in Indigenous policy,[20] the new language emphasised the engagement and participation of Indigenous communities, service delivery responsiveness to Indigenous needs, and partnerships and shared responsibility between governments and communities. The vacuum in Indigenous governance left by the abolition of ATSIC and other representative structures and the diminished role of Indigenous community organisations necessitated new approaches by government in seeking to engage with Indigenous communities. The Australian state and territory governments’ concept of Shared Responsibility Agreements represented an effort to enter agreements about services directly with Indigenous groups at the community level, or sometimes even the family level. Regional Partnership Agreements applied the same engagement principles at a regional level.[21] At the state and territory level, government policy frameworks emphasised ‘partnerships’ directly with Indigenous communities, through engagement mechanisms such as ‘negotiation tables’ in Qld and ‘Community Working Parties’ in NSW.[22]

Running parallel to governments’ core focus on mainstream service standards and its ancillary focus on better engagement with Indigenous communities has been the perennial challenge of how to improve coordination of service delivery across and within governments. The COAG trials agreed by COAG in 2002 were intended as a ‘whole-of-government cooperative approach’ in selected sites across Australia to ‘improve the way governments interact with each other and with communities to deliver more effective responses to the needs of Indigenous Australians’.[23] State and territory governments were also grappling to identify structural solutions to government coordination. For example, the Qld Government appointed Government Coordinators in remote communities and nominated agency CEOs as ‘Government Champions’ to lead engagement and coordinated government responses in specific Indigenous communities. These new approaches to coordination are underpinned by a belief that whole-of-government effort can best be coordinated, as well as aligned with community needs, by adopting a place-based approach focusing on an Indigenous community or region.

The NTER launched in 2007 reflected many of the principles in the new Indigenous policy orthodoxy. It represented a significant injection of funds for a suite of new services designed to close the gap in priority areas, with these services to be delivered by a combination of government agency staff and service providers contracted through competitive tenders. Coordination was to be achieved through GBMs in each community and new IEO positions were subsequently created to facilitate better engagement with communities.

1.6 National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery

The antecedents for the NPA RSD can be clearly identified in the preceding discussion of the evolving policy framework for remote Indigenous service delivery. In particular, the NPA RSD enshrines the three core themes of improving services, engagement and coordination.

The predominant focus continues to be on improving services as a means to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous life outcomes. The imperative for performance measurement can be seen in the commitment to baseline mapping and benchmarking against the range and standard of services in comparable non-Indigenous communities. LIPs were devised as a place-based mechanism to focus efforts on the priority actions and to reinforce the concept of accountability of governments and service providers for delivery of agreed outcomes. The elaborate reporting framework surrounding the implementation of the NPA RSD, including tracking every action in the LIPs as well as independent six-monthly reports by the Coordinator General for Remote Indigenous Services, give further effect to the principles of measurement and accountability for outcomes that have come to the fore in Indigenous policy in the past decade.

Complementary to the core focus on enhancing services, RSD continues the theme of improving coordination. Coordination was to be achieved by creating a ‘Single Government Interface’ co-locating Australian and State/Territory officers in Regional Operations Centres (ROCs) and employing GBMs or equivalents to lead coordination within each community. The GBM positions had direct precursors in the NTER, and similar positions also existed in Qld, employed by the State Government. Although not explicit in the NPA RSD, LIPs are also recognised as a tool to facilitate greater coordination by ensuring clarity and complementarity of the respective roles of various agencies and service providers.[24] This is especially important in areas where there are no defined statutory roles and a greater risk of duplication and overlap, such as delivery of programs for early childhood, parenting, family support and other areas of social and community development. Under the NPA RSD, like previous initiatives, coordination is an activity intended to be place-based, with a particular focus on the community level.

The principle of engagement is reflected in the RSD model through the elements of Local Reference Groups (LRG) and the IEOs, with the latter also drawn from the NTER model. The LRG was developed as the vehicle for the Single Government Interface (SGI) and participating agencies to engage with the community around the negotiation of the LIPs and then to progress the LIP actions.[25] The IEO is intended as a conduit for engagement between government and the local community. However, the RSD model envisages that engagement with the Indigenous community should not just be an activity led by ROC staff and the GBM in the negotiation and implementation of the LIP; it should also be part of the core business of service providers in their ongoing service delivery.[26] Thus, the model aims to change the way government and non-government service providers work in remote Indigenous communities.

A further objective of the RSD, closely linked to the theme of engagement, is to improve the level of governance and leadership within Indigenous communities and Indigenous community organisations (NPA RSD, Paragraph 15(c)). Inclusion of this objective appears to acknowledge one of the key lessons of the COAG trials, that stronger leadership and governance capacity is a prerequisite for Indigenous communities to be able to effectively engage or partner with governments and service providers.[27] In other words, governments cannot expect Indigenous communities to actively engage in planning and negotiation about service delivery priorities if they are not first supported to build functional governance and leadership structures that can represent and give voice to the community’s needs and aspirations. In the context of the RSD, building the governance and leadership capacity of the LRGs is important to continuing to negotiate and implement a LIP that reflects community priorities and engenders a sense of partnership. To support the governance and leadership objective, the agreement committed $67.7 million[28] over five and a half years for ‘Building community governance capacity’.

1.7 Findings

This section discusses each of the four key evaluation questions.

1.7.1 Service delivery improvements

Evaluation Question 1: Has access to and delivery of services improved?

This question is discussed under two sub-topics, quantum of services and quality and use of services.

Quantum of services

The evaluation found that the NPA RSD has had an impact in expanding the quantum of services and infrastructure.[29] The extent to which the prioritisation of RSD communities has had a net effect in closing the overall gap in levels of services across remote Indigenous Australia is more difficult to gauge. However, there are indications that the RSD planning and service improvement model, if used effectively by staff leading whole-of-government responses, can effectively leverage and optimise government investments to address service gaps and community priorities.

Examples of additional investments to RSD communities, arising from a suite of other NPAs[30] include the construction of new houses,[31] [32] Children and Family Centres; new or enhanced training; well‑being centres and health services; infrastructure to schools; expanded services and infrastructure related to men’s groups, women’s safe houses, youth sport and recreation programs; additional job opportunities through expanded services; housing construction; and new enterprises in areas such as arts and visitor accommodation.

While some of these service enhancements would have occurred regardless of the NPA RSD, stakeholders generally expressed the view that NPA RSD had contributed to these outcomes by bringing greater focus to drive change in these communities.[33] This perception is also mirrored in the online survey of local service providers. There was clear evidence of more services being provided to the communities, with a statistically significantly higher proportion of local service providers in RSD communities (43%) reporting that services had increased in the previous three years than those who worked in non-RSD communities (28%).[34]

The view that NPA RSD had contributed to expanding services and infrastructure was not uniform across the jurisdictions.[35] It seems that this outcome has depended on how effectively the NPA RSD has been used to leverage additional attention or funding for particular communities.[36] As the NPA RSD did not include significant new funding[37] for direct service delivery or infrastructure, the ability to expand services relied on using structures and processes (notably the ROC, community-based officers and the LIP process) to generate new focus and effort on addressing service gaps. This included leverage funding or enhanced services from mainstream sources that would not otherwise have been directed to remote Indigenous communities.[38]

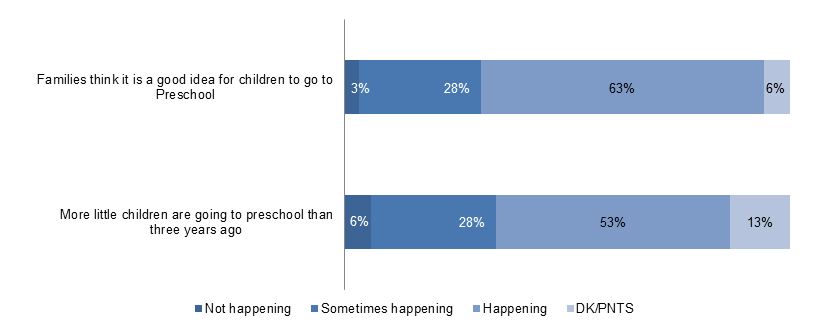

The qualitative data in the community research study showed that generally people feel there are more services ‘on the ground’ in their community. In particular, more services for young children and parents like Save the Children, Family Support Program, KidsMatter, new crèches and preschool centres were often mentioned.

The biggest changes nominated by community members included more houses or houses were fixed up (39%), improvements in infrastructure such as buildings, water, roads and sport facilities (15%), more jobs (10%) and more services for the people (10%).

One of the outputs of the NPA RSD was the detailed baseline mapping of social and economic indicators, government investments, services and service gaps in each of the 29 priority locations. The development of the LIPs was intended to be informed by the results of the baseline mapping reports. There are clear links between the baseline reports and the LIPs, with some LIPs explicitly mentioning the baseline reports. In addition some of the issues and service gaps identified in the baseline reports were included in the LIPs. However, there are not consistent links between the baseline reports and the LIPs. This is understandable as it would not have been appropriate for the LIP actions to simply reflect service gaps identified through baseline mapping, not least because the LIPs were also to be informed by community priorities.

While the mapping process identified a number of systemic service and infrastructure deficits, in many instances the findings reveal that service levels in RSD communities were the same if not better than their non-Indigenous comparative communities.[39] The mapping exercise revealed that service levels in the areas of education, employment, policing and social services (including welfare, youth, sport and recreation), were broadly consistent with those provided to non-Indigenous communities of a similar size and location. For example, all NPA RSD and comparative communities had a preschool and a primary school and all the NPA RSD schools were funded in accordance to broader state and NT Government funding formulas and approaches that give more resources to remote schools. This overall finding is not surprising as Australian Governments collectively spend more on Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians reflecting the relative need across the two groups for services. According to the Indigenous Expenditure Report (IER), estimated expenditure per head of population was $44,128 for Indigenous Australians, compared with $19,589 for other Australians (a ratio of 2.25:1) in 2010‑11. While the IER data are not available by remoteness area, unpublished data from the Commonwealth Grants Commission show that in 2010-11, state and territory spending on Indigenous Australians in very remote areas was $46,490 per person compared to $15,160 for non-Indigenous Australians: a ratio of over three to one.[40]

There were however notable gaps in the areas of municipal and essential services, primary access roads and emergency services. For example, the National Audit of Municipal and Essential Services found that there was a significant gap in infrastructure, and municipal and essential service delivery in RSD communities when assessed against the agreed base level standards[41] and compared to the non-Indigenous comparison communities.[42] Services and infrastructure in a number of RSD communities did not meet these base level standards, particularly in relation to water, waste, animal management and environmental health provision.[43]

Another notable gap was primary access roads, with access roads in a number of RSD communities partly unsealed. In contrast, all of the comparison communities in the baseline mapping exercise, with the exception of Nhulunbuy had all-weather sealed access roads. [44] Another notable issue was the level of private sector activity. The baseline reports showed that most RSD communities had considerably less private sector activity and services than comparable non-Indigenous communities. The RSD communities that are towns such as Walgett and Fitzroy Crossing had better access to private sector services than other RSD communities.

Providing standards of services comparable to those of non-Indigenous communities of similar size and location does not necessarily guarantee service equity[45] and the baseline mapping exercise highlighted that where gaps in services exist, the reasons are complex. They arise from a mix of historical, social and economic causes that will not be remedied by matching the range and class of service levels to those of non-Indigenous communities of similar size and location. In addition the needs of remote Indigenous communities are considerably different from those of the comparison communities.

The availability of services and other factors are considered in decisions people make about where they are going to live. Biddle and Markham conducted a regression analysis of population mobility using 2011 Census data.[46] Controlling for a number of factors, the regression analysis shows that RSD communities and Territory Growth Towns (TGT)[47] had, other things being equal, a lower level of outward migration than other areas. The authors also found that those Indigenous people who left a remote dispersed settlement, were significantly and substantially more likely to move to a RSD community or a TGT than another location type. While it is not possible to establish causality, this analysis suggests that the additional services provided to RSD communities may have affected migration patterns.

Quality and use of services

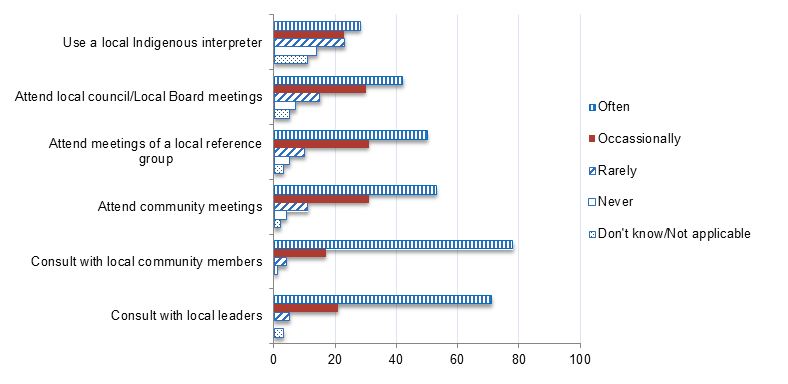

The NPA RSD included a number of measures intended to improve the quality, availability, accessibility and cultural appropriateness of services. Staff delivering government services were given cultural awareness training and interpreter services were made more widely available, which contributed to services being more culturally appropriate and accessible. GBMs and IEOs assisted community members and organisations to navigate, negotiate with and access services.

The available evidence, however, does not permit a robust assessment of whether quality[48] and usage of services has improved in RSD communities to date.

In practice, service quality benchmarks framed in terms of suitability, cultural inclusiveness or comparability with other communities are difficult to precisely define. There are few existing national standards that can be referenced for remote Indigenous community service delivery. The concept of uniform standards across all Indigenous communities also runs counter to the NPA RSD’s philosophy of negotiating place-based service priorities through dialogue with local communities. Nevertheless, the Australian Government has been working to develop suitable service standards during the implementation of the NPA RSD. The ANAO notes that agreed standards for municipal and essential services were able to be negotiated with jurisdictions at the time of the baseline mapping but this was not possible for other areas such as education.[49] The agreed standards for municipal and essential services were based on pre-existing service guidelines and in some cases they were based on existing service standards. Similar pre-existing guidelines and standards did not exist for most services as was noted in the development of the baseline mapping reports.[50] The RSD Implementation Review reports that development of further service standards is in progress and was expected to be completed in 2013.[51]

In the absence of defined standards and the challenges of performance measurement, the evaluation is unable to assess whether the ‘quality’ of services has improved in this strict technical sense. In the broader sense of ‘higher quality’, some information is available from the community research study, service provider survey, and the stakeholder interviews.

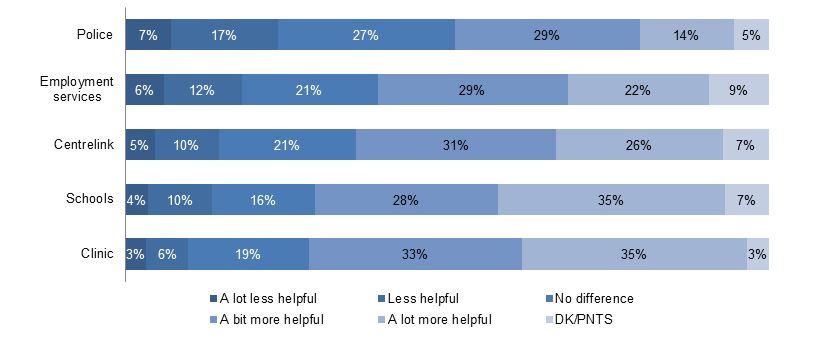

The community research study asked community members if they thought five key services (police, health clinic, and Centrelink, school and employment services) had become more or less helpful since the start of the NPA RSD. The data show that most people think the health clinic (68%), school (63%), Centrelink (57%), employment services (51%) and to a lesser extent, the police (43%), have become more helpful over the past three years.

The community research study shows that more services are being utilised by community members. However, there was recognition by community members that behavioural change by individuals is still needed within communities to more fully utilise the services available. Examples given by respondents included sending kids to school, reducing violence and substance abuse, looking for employment and training and people taking full advantage of services. When asked who they would talk to about community needs and change, ‘people working in services’ were nominated by 25 per cent of respondents.

Half of all community members felt their community was on the way up or improving and ‘more services’ was one of the main four reasons given for this perception of life in community.

However, the qualitative data also revealed the following concerns: coordination in service delivery, duplication of effort, people ‘falling through the cracks’, and a lack of follow up. Generally it was felt that if services coordinated their efforts more effectively these problems would be mitigated. The qualitative data also show a strong desire for more local people to be employed in local services, particularly management positions. This would provide more sense of community involvement and control.

The survey of service providers suggests that while the focus on service delivery may have had some positive impact, there is an anecdotal view in some locations that rapid expansion of services has meant a trade-off in the short-term quality of services and the ability to engage the community to ensure high service usage levels. This view was substantiated in the stakeholder interviews[52] with some stakeholders concerned that the increase in services actually had a detrimental effect, by exacerbating competition between providers and confusing the community. On the other hand, an acknowledgment by some government stakeholders that the establishment of new services had been expedited to address urgent shortfalls, the focus now needed to switch to improving service quality and coordination.

The survey of service providers[53] found that providers were slightly more positive about improvements in accessibility of services in the RSD communities than the non-RSD communities. However, the most common response was that accessibility had remained about the same in both RSD and non-RSD communities.

In the qualitative interviews, stakeholders raised various issues about the accessibility of both existing services and the newly introduced services.[54] A key issue was the ability of residents to access visiting services that are funded to occasionally visit remote communities. In some locations, the accelerated roll-out of services and perceptions about poor engagement (see Engagement, coordination and capacity below) led to confusion amongst community members about the roles of different services.

1.7.2 Coordination, engagement and capacity

Evaluation Question 2: Has the capacity of communities and governments to engage with one another improved?

Due to the complexity of this question, the section has been divided into three sub-topics: coordination of government services, government capacity to engage communities, and community capacity to engage with government. Each topic starts with a brief description of the context followed by a summary of the evaluation findings. Further discussion is provided in Appendix A.

Coordination of government services

A broad aim of the NPA RSD is to improve the coordination efforts of government agencies.[55] Government coordination effort has been commonly cited as an impediment to overcoming Indigenous disadvantage[56], with the historically complex demarcations between different levels of government and the increasing number of NGO service providers[57] exacerbating the problem. The past decade has seen considerable focus on more coordinated approaches, often described in terms of ‘whole-of-government’ or ‘joined-up government’.[58]

In remote Indigenous communities, the goal of service delivery coordination involves improving the connections between service entities to improve the service delivery outcomes. Coordination in this sense can be seen as a continuum that extends from creating simple linkages between discrete entities; to increased coordination in a structured and planned manner; to full integration where discrete services cease to exist, replaced by a new service, unit or program.[59]

The RSD model follows a succession of Australian government strategies to improve coordination at both the strategic policy and operational service delivery levels. These include the COAG trials starting in 2002, the creation of Indigenous Coordination Centres (ICCs) in 2004,[60] and the introduction of GBMs as part of the NTER in 2007. At the strategic policy level, the bilateral plans and Boards of Management (BoMs) within each jurisdiction are intended to drive high-level coordination between and across governments.[61] At the service delivery level, the key element intended to contribute to better coordination between governments is the creation of a ‘Single Government Interface’ for each NPA RSD site, comprising the ROC and the community-based GBM and IEO positions. The LIP is intended as a further tool to facilitate a joint effort by governments and community to identify local priorities, actions for future investment and respective accountability roles.

The service delivery principles[62] espoused in the NPA RSD extend governments’ coordination role to include coordination with the myriad NGOs delivering services funded by governments.[63] Thus, the LIP priority planning process, in keeping with a philosophy of shared responsibility has also sought to capture the roles, responsibilities and contributions of NGOs and Indigenous communities themselves. In these regards, the RSD model is more ambitious than strategies focused purely on coordination between government agencies. This approach is consistent with trends in public policy literature emphasising the importance of ‘networked governance’ and ‘governance partnerships’.[64]

The evaluation found that components of the RSD model intended to improve coordination between governments had varying degrees of success in practice:

- some early gains in strategic coordination between levels of government, diminished over time[65]

- ROCs were considered to be effective in some jurisdictions but not others[66]

- local service provider meetings were viewed as having only limited impact in improving service coordination.

In the service provider survey the most common response from local service providers was that the key components of the SGI (ROCs, GBMs and IEOs) were ‘quite effective’, although more respondents were positive about the effectiveness of the locally based GBMs than they were about the ROCs.[67]

GBMs were widely considered by stakeholders as the most effective element of the model for improving coordination.[68] [69] [70] [71]

While most stakeholders considered the concept of the LIP to have merit as a means of strategically planning and coordinating service delivery at a place-based level,[72] the actual implementation of the LIP concept has tended to fall short of this objective.[73] [74]

The utility of LIPs as a tool to assist in coordinating government service delivery was perceived by many stakeholders to be constrained by the format of the plans. Most observers commented on the size and ambitious scope of the LIPs. The NPA RSD Implementation Review reported that the LIPs contain over 4000 action items, suggesting they ‘could be streamlined and better targeted toward high priority activities, such as addressing service gaps’.[75] Two-thirds of the respondents to the service provider survey who were able to answer the relevant question said that the LIPs have not been effective in ‘generating change in local communities’.[76]

This last point highlights the tension between instituting whole-of-government planning and coordination of services at the same time as trying to provide the vehicle to engage and partner the community.[77] It has proven a difficult exercise for the LIP process to perform both functions. Shorter plans containing priority actions achievable in the short to medium term would be more effective as the catalyst for proactive partnerships. However, such a plan may not be comprehensive enough as a tool for whole-of-government service delivery planning that locks in the accountability of a wide range of agencies for their service delivery commitments in a community.

What, then, has been the net effect of all of these measures on the perceived overall level of coordination of government service delivery in remote Indigenous communities? There were differing views expressed by stakeholders on this question. Some stakeholders were able to identify positive changes, some reported no improvement and others believed that the situation was, paradoxically, worse under the NPA RSD due to an increase in the number of services in communities.[78]

Stakeholders who suggested that coordination had worsened since additional services had been introduced in RSD communities often cited examples of increased duplication of services and in some cases higher levels of community confusion as a result of new organisations being funded to work with similar client groups.[79]

Key barriers to improved coordination identified in the evaluation included:

- the need for better engagement with the NGO sector

- the reliance on larger NGOs with less-developed local networks in preference to Indigenous community organisations that are better linked into local networks[80]

- the competitive funding environment for NGO service delivery[81]

- the tendency for some government and NGO service providers to operate in ‘silos’ rather than valuing linkages to coordinate and integrate their efforts[82] [83]

- the need to develop capacity or skills of service provider staff to work collaboratively or to adopt a more holistic, community development framework

- the lack of authority for local staff to go beyond existing structures in order to innovate and collaborate[84]

- a deeper capacity issue for government.[85] [86]

Local service providers were more positive than negative in the online survey on the question of whether coordination had improved in RSD communities in the past three years. On this measure, 35 per cent said coordination of services was better and 16 per cent said it was worse, however 37 per cent said it was about the same (and 12% did not know).

The above evaluation findings are consistent with research on the ICC model for whole-of-government coordination.[87] That research found that mechanisms such as co-locating staff from multiple agencies within a single office were insufficient to improve coordination in the face of unsupportive system architecture for joined up government, a programmatic focus and centralised decision-making. Many of these barriers were also identified in the evaluations of the COAG trials.[88] While the NPA RSD coordination mechanisms have gone some way, more fundamental reforms are needed to achieve fully integrated, seamless service delivery systems in remote Indigenous communities.[89]

Governments capacity to engage communities

Effective processes of engagement are critical for achieving a conversation not just to improve coordination and align services with priorities, but also to improve responsiveness to community needs and aspirations.

In this context, engagement refers to how governments and service providers (including NGOs and funded services) interact with members of remote Indigenous communities. Engagement by governments with the ‘community’ takes place at several levels, including: individual service recipients, families, leaders, Indigenous organisations and representative bodies.

Key elements in the NPA RSD to improve engagement by governments with communities include:

- the SGI (comprising the ROC and the community-based GBMs and IEOs) is intended to lead government’s processes of engagement with communities

- the LIPs are intended to be the vehicle for governments to engage and partner with the community to identify priorities and plan collaborative responses

- the LRG is intended to be the focal point for government’s engagement with community around LIP planning and implementation, and for discussing service delivery issues more generally.

By late 2011, the Coordinator General concluded that the SGI is working and showing positive results, noting that ‘one of the strengths of the Remote Service Delivery approach is the provision of a strong and permanent presence in Indigenous communities that allows the building of long-term relationships with community members’.[90]

The evaluation, through the stakeholder interviews and service provider survey has also confirmed that the community-based GBM and IEO staff[91] had a significant and positive impact on government’s engagement with remote Indigenous communities. The majority of stakeholders considered the IEO role to be critical. Government stakeholders in particular felt that the IEO provided valuable information about the community that they would not otherwise be able to access.

Excluding not stated responses, 69 per cent of respondents to the service provider survey reported that GBMs were effective in helping community engagement while 68 per cent of respondents noted that IEOs were effective.[92]

Despite some general criticisms around the LIP processes, there have clearly been jurisdictional and regional differences, with better engagement processes adopted in some locations. Although the aggregated service provider survey varied in relation to the effectiveness of the LIPs in helping community engagement, there was a very positive response in WA, compared to a largely negative response in NSW and SA; while the response in the other two jurisdictions was more or less split.[93] The stakeholder interviews[94] contained several positive endorsements of the engagement approaches used by some ROCs and some of these good practice case studies such as governance and cultural mapping are highlighted in the Coordinator General’s reports.[95] A different view was the lack of feedback to some communities around the LIP implementation and that the LIP review process has been slow in most locations.[96]

There is a tension between the LIP’s dual functions as a tool for service delivery coordination and community engagement. Over time, stakeholders have reported that the model has become inwardly focused on government service provision and coordination issues, with increasingly limited involvement of the community in discussions about the progress of the LIP, ongoing planning and priority-setting.[97]

The community research study tried to measure the engagement of local people in the communities by investigating the knowledge level of the SGI components. The LRG was the most well-known component with 61 per cent of respondents being aware of their LRG. Over half of the people knew about the IEO in their community (54%) while less than half knew about the GBM in their community (43%). Knowledge of the RSD model appears to be higher for older respondents.

In relation to the LIP, over half (52%) answered ‘no’ when asked if they knew about the LIP, with one third (35%) of respondents answering ‘yes’.

Of the people who had heard of the LIP, thirty per cent thought that it told the ‘right story’ about their community and a further 18 per cent thought it told the right story ‘a little bit’. Quite a number knew about the LIP but had not seen it (34%). Older community members (45 plus) and the employed were more likely than others to be aware of the plan.

While the development of LIPs led to a short burst of positive community engagement during 2010, this largely fell short of a genuine negotiation about service delivery priorities to institute an ongoing partnership between governments and Indigenous communities. Reasons identified by stakeholders included:

- the short timeframes for LIP completion

- in some locations, top-down engagement approaches

- the design of LIPs needing to address multiple areas simultaneously rather than strategically focused plans on place-based enablers for change

- governments’ evolving capacity to engage communities in the way the NPA RSD intended

- in practice, the aspect of the LIP concept focused on service delivery coordination and accountability has taken precedence over its other intended function as a partnership and engagement mechanism

- while the LIP has been a useful coordination tool, in most places it has not fulfilled the NPA RSD goal of serving as a focal point for an ongoing conversation about service delivery improvement

- the variable effectiveness of the LRG concept as a mechanism for governments’ engagement with communities around the LIPs in many places

- insufficient governance capacity-building assistance to these LRGs.

In respect of service providers, there is limited clear evidence to date that service providers have improved the quality of their engagement with Indigenous communities. Some providers have benefited from using the IEOs and have participated in the ROC-led engagement processes around the LIPs, but there are concerns about the sustainability of engagement if the NPA RSD mechanisms do not continue. The increase in external organisations delivering new services in RSD communities heightens the need for community engagement, and the difficulty in achieving it.

Ultimately, the evaluation found that the LRG concept has worked as an effective community engagement channel where it was built on strong, functional community governance structures already in place. The concept has not been effective in locations where community governance and leadership capacity was underdeveloped. The RSD model has generally had limited impact in building this capacity where it was lacking and is further discussed under the subsection Community capacity to engage with government.

The variable quality of the government’s engagement with Indigenous communities underscores a frequently raised question about the capacity of government staff for effective community engagement. A 2004 parliamentary committee inquiry into capacity-building and service delivery in Indigenous communities concluded that the capacity of governments itself was ‘the area in which the most significant effort was needed in order to facilitate capacity-building in Indigenous organisations and communities’.[98] The report emphasised that ‘the capacity of agency staff is particularly important for the establishment and maintenance of partnerships with Indigenous communities’.[99] The evaluation of the COAG trials in 2006 also noted that ‘government staff need training in how to engage with respect for the protocols and processes in Indigenous communities’.[100]