Being employed improves the health, living standards and the social and emotional well being of individuals, families and communities. Employment not only brings financial independence and choice, it also contributes to self-esteem. Growing up in a household where one or both parents are employed gives children strong role models to shape their own aspirations.

target

Halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within a decade (by 2018). (No new data)21- This target is not on track. However, although no progress has been made against the target since 2008, Indigenous employment rates are considerably higher now than they were in the early 1990s. Historically, cyclical softening of the labour market, where employment levels have fluctuated, has impacted adversely on employment prospects.

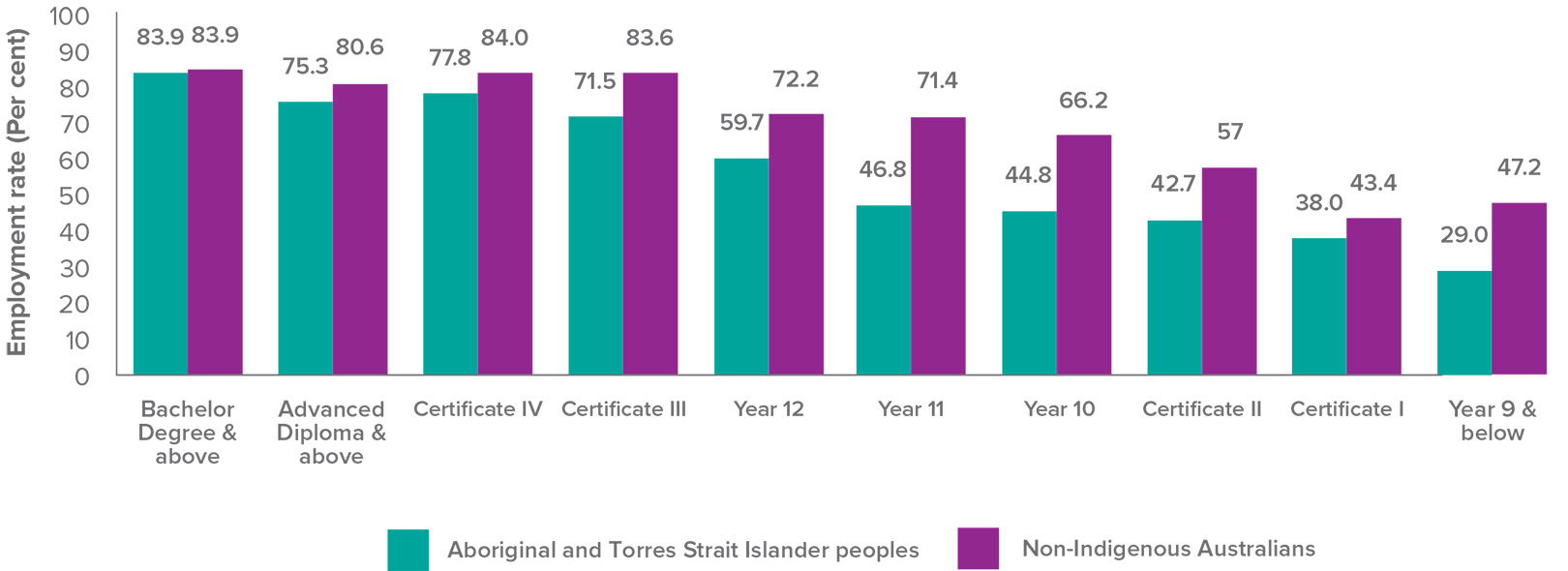

- There is a strong link between education and employment – at high levels of education there is virtually no employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

- Employment opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are being generated through setting targets for government procurement, public service employment and through the efforts of corporate Australia.

- Indigenous employment rates are considerably higher in the major cities than in remote areas.

Border Monitoring on Saibai Island, left to right; Harry David, Margaret Dau, Jerry Babia and Peter Levi. Border Monitoring Officers are recruited directly from Torres Strait Islander communities to monitor and report the arrival and departure of traditional visitors from Papua New Guinea.

What progress is being made?

There has been no new national Indigenous employment data released since last year’s report. New data on Indigenous employment will be available in April 2016 from the ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS). Progress against this target is measured using data on the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of workforce age (15-64 years) who are employed (the employment rate).

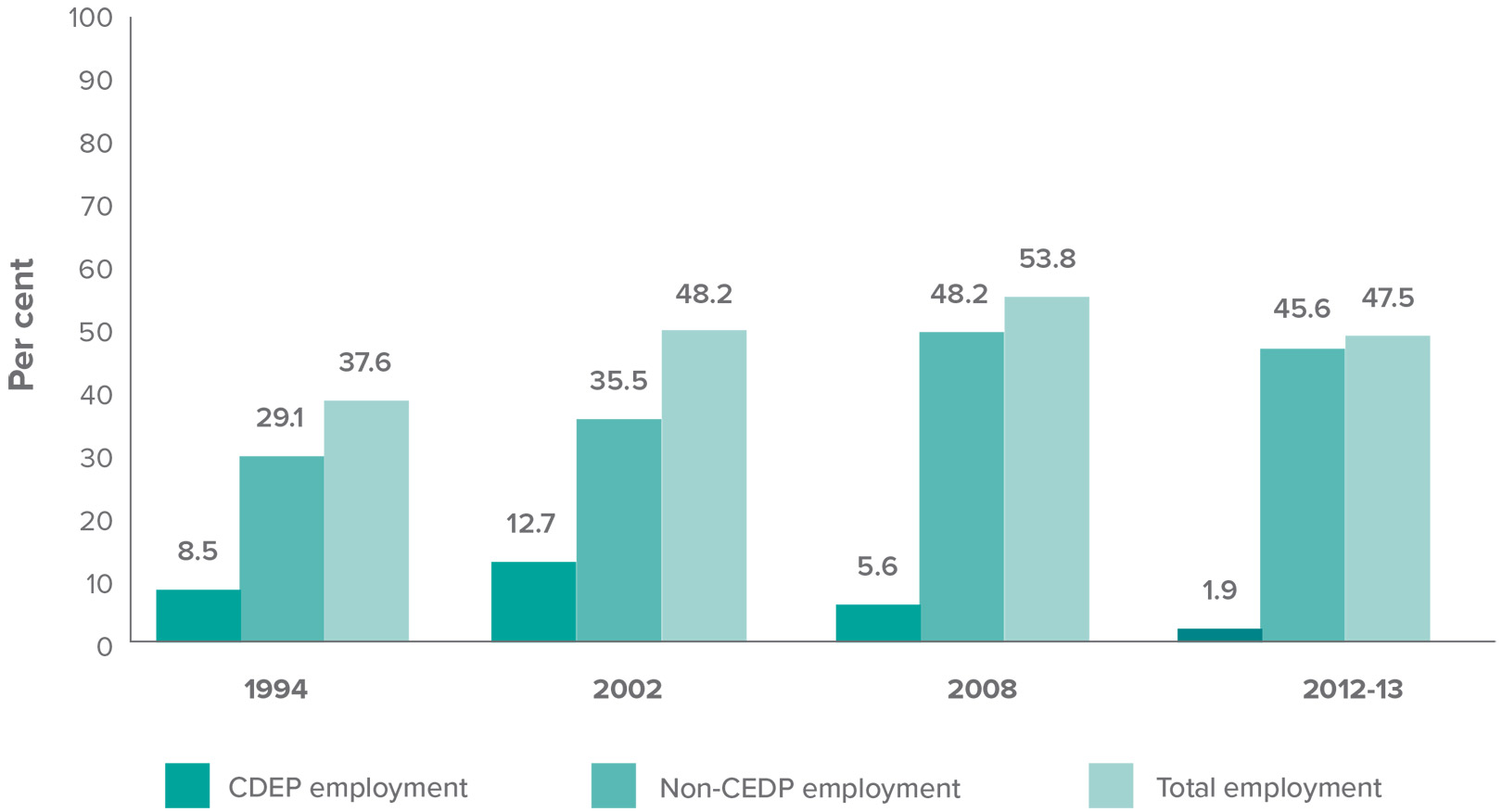

This target is not on track. The Indigenous employment rate fell from 53.8 per cent in 2008 to 47.5 per cent in 2012-13. This occurred in the context of a general softening in the labour market over this period. The overall employment rate for all Australians fell from 73.4 per cent in June 2008 to 72.1 per cent in June 2013, with sharper falls evident for men with relatively low levels of education. The employment rate for men with a Year 10 or below level of education fell from 67.4 per cent in 2008 to 63.3 per cent in 2013 22. It is therefore not surprising the employment rate for Indigenous men fell sharply from 2008 to 2012-13 as nearly half of all Indigenous men of workforce age have a Year 10 or below level of education23.

In its independent report on progress against the employment target, the Productivity Commission acknowledged “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians have almost certainly been more adversely affected by recent cyclical softness in the labour market” (PC 2015, p. 11).

Another important factor in this decline is the gradual cessation of Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP), which ceased operations on 30 June 2015. The CDEP scheme was an Australian Government initiative that enabled job seekers (usually members of Indigenous communities) to undertake various work and training activities, managed by local Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community organisations. During the life of the programme, the ABS classified CDEP participants as being employed24. The decline in CDEP participants between 2008 and 2012-13 accounted for 60 per cent of the decline in the Indigenous employment rate over this period.

To get a more accurate sense of the employment gap, it is better to focus on the non-CDEP employment rate and how this has changed over time. While this rate fell between 2008 and 2012-13, the decline was not statistically significant.

It is also worth noting while there has been no progress against this target there have been some longer-term improvements. The Indigenous employment rate was considerably higher in 2012-13 (47.5 per cent) than 1994 (37.6 per cent) (Figure 7).

Source: ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002 & 2008, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2004-05, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (core component) 2012-13

Source: ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002 & 2008, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2004-05, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (core component) 2012-13

Indigenous employment rates vary sharply by geography. In 2012-13, only 30.4 per cent of all Indigenous people of workforce age (15-64 years) in very remote areas were employed in a non-CDEP job compared with 49.8 per cent of those living in the major cities. Most Indigenous men of workforce age in the major cities (55.8 per cent) and inner regional areas (54.3 per cent) were employed in 2012-13.

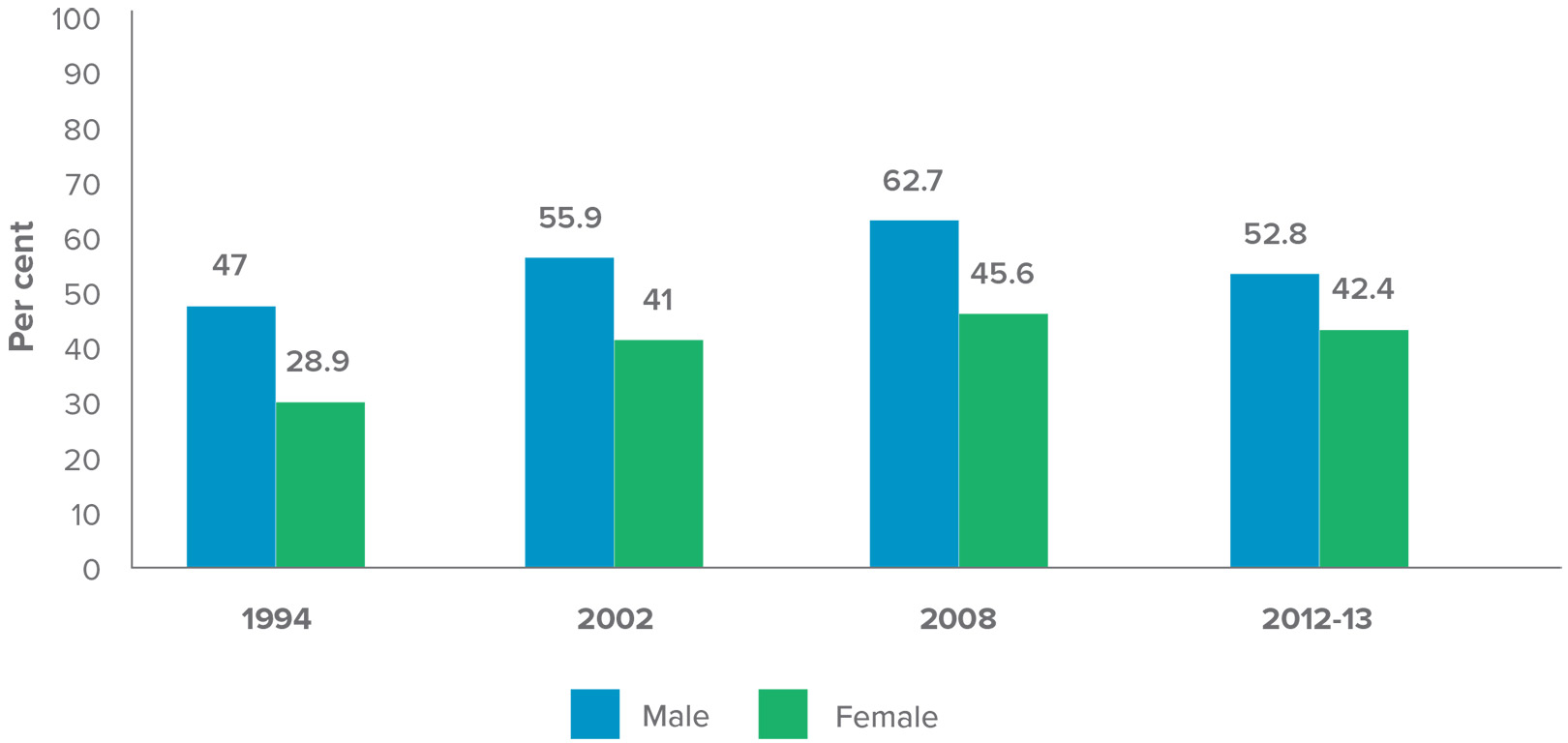

The longer-term data tells an important story by gender. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have made substantial progress in employment over the longer term. Despite a small fall after 2008, the employment rate for working aged women in 2012-13 (42.4 per cent) is still higher than the mid-1990s (28.9 per cent). Also, while Indigenous female employment rates are considerably lower than Indigenous male employment rates, the gap has narrowed considerably since 199425.

Source: ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002 & 2008, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Core Component) 2012-13

Source: ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002 & 2008, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Core Component) 2012-13

There is a strong link between education and employment. As noted in Chapter Two there is no significant difference between the subsequent educational outcomes of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students once we control for academic achievement at age 15. This, allied with the fact the employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people declines as the level of education increases, highlights just how important education is for closing the employment gap (see Figure 9). While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are considerably less likely to have a Certificate III or higher levels of qualification there have been some longer-term improvements.

For example, in 1971 only 4.9 per cent of all Indigenous men aged 20-64 years had a post school qualification – by 2011 this proportion had risen to 31 per cent.

While closing the employment gap is very challenging we know improving education levels can make an important difference. In each year cohort the number of Indigenous people is not large. For example, in 2015 there were 16,500 Indigenous eight-year-olds. If we focus on improving educational outcomes for each cohort of school age children, this will in turn have a positive impact on the employment gap in years to come.

Source: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2011

Source: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2011

Accelerating progress

Between 1 September 2013 and 31 December 2015, Government employment programmes under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, including the Employment Parity Initiative, the Community Development Programme and Vocational Training and Employment Centres, have facilitated more than 36,000 jobs for Indigenous Australians.

In addition, in its first six months (to 31 December 2015), the Government’s employment service for urban and regional centres jobactive has achieved 13,617 job placements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Strong economic growth and sustainable development are precursors for increasing employment opportunities in the labour market. Cyclical softening of the labour market and changes to the composition of labour demand – employers requiring higher skilled workers – have significantly impacted the labour market opportunities for Indigenous Australians, particularly for those with lower education and skills.

Transitioning from school to further education, training and employment

The transition from school to work or further education can be a make or break point in a young person’s life. Australian Government programmes to support this transition include:

- Transition to Work initiative which will help around 29,000 15 to 21-year-olds each year. It is anticipated that 16 to 20 per cent of participants will be young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- Empowering YOUth Initiatives encourage not-for-profit and non-government organisations to run innovative initiatives for young people to prevent long-term unemployment, remove barriers to employment and help sustain employment. Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, aged between 15 and 24 years who are long-term unemployed or at risk of long-term welfare dependency, are one of the priority groups for round one funding.

- A number of projects which focus on school leavers and training linked to employment (funded under the demand-driven employment stream of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy: Jobs, Land and Economy Programme).

Participants in the Indigenous Australian Government Development Programme (IAGDP) pictured with the Minister for Indigenous Affairs, Senator Nigel Scullion in Canberra. The IAGDP is a 15 month programme that combines ongoing employment with structured learning to increase the representation of Indigenous Australians working in the Australian Government.

Creating opportunities for employment

Leading by example, the Government has set a new target of three per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation in the Australian Government public sector by 2018. The Commonwealth Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employment Strategy aims to increase the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian Government public sector to 9,270. For the first time, the Government has set robust agency-level targets for Indigenous representation. State and territory governments have also set targets for Indigenous employment.

Under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, support is provided to connect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of working age with real and sustainable employment. Community by community, business by business, jobs are tailored to address employer demand and local circumstances and needs. Between 1 July 2014, when the Indigenous Advancement Strategy was introduced, and 31 December 2015 demand-driven projects supported more than 5,300 employment opportunities for Indigenous job seekers.

Murray Riley moved to Melbourne with his wife and their young son to join Crown’s Indigenous employment programme under the Employment Parity Initiative. Now working as a Training Administrator, Murray is an enthusiastic and highly respected employee. He says he’s come a long way – both geographically and professionally – since moving from Perth and is proud that he had the courage and determination to make the move when he didn’t know anyone in Melbourne.

The Government is partnering with some of Australia’s largest employers to support an additional 20,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into real jobs by 2020. Ten companies – Compass Group, Accor Pacific, ISS Facility Services, Crown Resorts, Sodexo Australia, Spotless Facility Services, Hutchinson Builders, Woolworths Limited, MSS Security and St Vincent’s Health Australia – are now signed up to the Employment Parity Initiative, securing 6,815 new jobs. There are plans for another three contracts in early 2016. These agreements combined will ensure 8,658 unemployed Indigenous Australians will have access to sustainable jobs.

The Government is also supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to move into jobs through Vocational Training and Employment Centres (VTECs) with almost 3,500 Indigenous Australians starting employment since the pilot started in 2014. VTECs connect Indigenous job seekers with jobs and bring together the support services necessary to prepare them for long‑term employment.

case study Charting a new career pathway

Denise Sampi from East Kimberley learning new skills.

Born and raised in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, Denise Sampi had worked as a tour guide and an aged care worker but wanted a different career pathway. She started with the Vocational Training and Employment Centres programme at the beginning of 2015, undertaking a work-readiness course. A highlight was being part of a team working alongside celebrity chef Matt Moran in the acclaimed ‘Kimberley Kitchen’ event.

Her enhanced skills – such as literacy and numeracy plus her strong work ethic – helped her land a job as an activity supervisor with local organisation East Kimberley Job Pathways. As a result of her determination and commitment, she was recently nominated for the Kimberley Encouragement Award as part of the 2015 Kimberley Group Training Excellence Awards.

Remote employment services

In very remote areas, almost one in five adults of workforce age receives income support payments. People in remote Australia tend to move onto welfare at a younger age and stay on it for longer than people in urban areas. The difficulties in accessing training and the absence of strong labour markets make it difficult to secure continuous, paid employment. These unique circumstances require a different approach to employment and participation than urban Australia.

In 2015 the Government reformed remote employment services to tackle the challenges created by high levels of welfare dependency. The newly-established Community Development Programme (CDP) provides:

- Opportunities for job seekers (18 to 49 years) to contribute to their communities, gain experience and skills and build self-esteem while looking for paid employment.

- Culturally appropriate, tailored activities in a range of areas including construction and maintenance, administration, the arts, fisheries, agriculture and horticulture, caring for country, food preparation and nutrition, elder care and childcare.

- Opportunities for formal study in a range of fields including business, housing maintenance, early childhood education, hospitality, agriculture and conservation and land management.

- Access to driver training and basic car maintenance, recognising that the lack of a driver’s licence can be a significant barrier to employment.

- Placements with local employers, including local councils, energy organisations and childcare and aged care facilities, for up to six months of work experience.

- Support to overcome non-vocational barriers to employment such as poor literacy and numeracy, homelessness, domestic violence or substance misuse.

In the first six months of implementation, CDP has supported Indigenous Australians into 2,778 jobs. There was also a significant increase in the number of remote Indigenous job seekers contributing to their communities and developing skills while they look for work – from 46.7 per cent at 30 June 2015 (under the former Remote Jobs and Communities Programme) to 68.5 per cent (17,138 job seekers) at 31 December 2015. As of 14 December 2015, 620 Indigenous job seekers had been placed in hosted placements in industries including childcare, fisheries, landscaping and conservation, hospitality and construction.

case study Community Development Programme job seekers promoting food security in the desert

Jason Marriott (CDP Supervisor) and Kristopher Stuart growing fresh food in the desert.

In the South Australian communities of Colebrook, Beltana and Marree providers have been working with job seekers to pilot an aquaponics project to provide an innovative solution to the challenges of growing, cultivating and distributing fresh food in the desert. Aquaponics combines both aquaculture and hydroponics where waste from the fish provides nutrients for the plants.

Around 30 job seekers are participating and gaining valuable skills through building tanks, fitting out the enclosed environments and growing fresh fruit and vegetables. Their training and experience will result in long-term economic and environmental benefits for their communities, including producing food in a region that would otherwise be considered arid and unsuitable for farming.

case study Furniture making boosts Milingimbi economy

Brendan Marrilama being instructed by Jimmy Burpur at the Milingimbi Bukmak workshop

In the small island community of Milingimbi in the Northern Territory, a furniture-making enterprise called Bukmak is giving job seekers new skills and stimulating the local economy.

Community Development Programme provider Arnhem Land Progress Association Aboriginal Corporation (ALPA) has set up the new venture in partnership with commercial fit-out company Ramvec and Swinburne University of Technology.

The completed products are sold locally in the community through ALPA’s Milingimbi store with plans to provide a separate line of high-end products for sale in major cities around Australia.

Caring for the environment

Australian Government programmes to protect the environment are also creating jobs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

- Indigenous Rangers Programme – 775 full-time equivalent Indigenous ranger positions are funded providing 1,600 people with employment in full-time, part-time and casual ranger jobs. Junior ranger programmes are also being developed to support school attendance and ensure the passing down of traditional ecological knowledge.

- Specialised Indigenous Ranger Programme – supports the skill diversification of current Indigenous Rangers to ensure the sustainable harvest of marine turtles and dugongs.

- Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) programme – complements the work of ranger groups. There are over 550 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in full-time, part-time and casual jobs under the IPA programme.

- National Landcare Programme – focuses on partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities so they can fully participate in land and sea management resulting in the employment of around 50 people and a number of Indigenous traineeships in regional areas.

- Green Army Programme – young people work on local environmental and heritage conservation programmes, developing on the job skills and the potential for vocational training leading to further qualifications. With a target of engaging 1,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants in its first five years, 725 were engaged by November 2015.

- Emissions Reduction Fund projects – Indigenous land managers participate in domestic carbon markets, particularly savanna fire management activities. This is creating employment, economic, social and cultural opportunities in remote northern Australian communities. Savanna fire management projects combine Indigenous land management practices with modern science, and have already generated more than 1.5 million tonnes of emissions reduction.

- National Environmental Research Programme – 279 local Indigenous Australians, including Indigenous rangers and Traditional Owners, were employed on 16 research projects which aimed to improve biodiversity conservation in northern Australia between 2011 and 2015.

Jesse Williams tracking Tasmanian Devils during the save the Tasmanian Devil Program, Bronte Park Tasmania.

case study Karmel Milson – working on country

Riverland Ranger Karmel Milson and her sons Jack and Kallum from South Australia.

You only have to talk to the people involved in the Riverland Rangers Working on Country programme to realise the positive effect of employment.

“I’ve been saying to my kids for years, ‘can’t afford that, can’t afford that’. Now, I can pay my bills, I can give my kids everything,” says Karmel Milson a ranger working at Calperum Station, north of Renmark in South Australia. “My youngest – he’s eight – wants to be a Calperum Ranger, and my kids are proud of me.”

The Riverland Rangers project is designed to support the Aboriginal community’s desires for greater involvement in natural and cultural resources management and to address community problems such as high unemployment, low school attendance and health and wellbeing issues. The team of six Aboriginal rangers and a coordinator, work primarily on Calperum and Taylorville Stations in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Urban and regional employment services – jobactive

With almost 80 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in cities and regional centres, mainstream employment services have a vital role in boosting Indigenous employment. The Government has introduced reforms and invested $6.8 billion over four years in jobactive – its new employment service for urban and regional centres. With a more outcomes-focused approach, it has stronger participation requirements to effectively engage job seekers and align their obligations with community expectations.

For the first time, jobactive employment services providers have specific Indigenous employment targets which are part of a provider’s ongoing assessment, creating a stronger incentive for providers to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander job seekers to find and keep a job. Over the first six months of operations (to 31 December 2015), jobactive has achieved 13,617 job placements for Indigenous Australians.

In Sydney, jobactive job seekers are gaining entry level technical skills to work on the Sydney Metro Northwest project. As well as helping to meet the workforce needs of the rail link project, this collaborative effort with the New South Wales State Government has resulted in more than 40 job seekers gaining employment, including seven Indigenous job seekers. This successful model can be adapted to other industries.