Transforming lives through jobs

"Engaging the unique skills and knowledge of Indigenous people can have a positive impact in all organisations. It plays a key role in assisting organisations to develop mutually beneficial Indigenous employment strategies. Indigenous employees bring different perspectives, experiences and knowledge, which can create long-term value for organisations and individuals. These positive economic and social outcomes provide a workplace of choice for Indigenous people and the wider community." - Senior HR Aboriginal Employment Consultant – Chevron Australia, Rishelle Hume

The Centre for Appropriate Technology has a core commitment to providing employment for Aboriginal employees with high quality design and fabrication skills. Here, Project Manager Elliat Rich and Upholster James Young are seen measuring the panels for the Designer Dome. This project was completed at the centre's Alice Springs workshop, employing exclusively Aboriginal workers.

Transforming lives through employment

The power of a job can be transformational through the provision of not only greater financial independence, but also skills and training that can open up future opportunities.

Employment also contributes significantly to people’s health, wellbeing and social outcomes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders thrive in workplaces across the country – from Arnhem Land in the north, to Australia’s biggest city, Sydney, on the east coast and over to the Kimberley in the west.

The Australian Government is implementing a range of Indigenous-specific and mainstream initiatives that are supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into work. The emphasis is on achieving 26-week employment outcomes because this is a key to ensuring people remain in the workforce.

- The Government’s remote employment services initiative, the Community Development Programme (CDP), is successfully supporting job seekers to transition from welfare into work.

- The Indigenous Procurement Policy is ensuring Indigenous businesses win a bigger slice of the Commonwealth’s procurement spend. This, in turn, supports Indigenous employment as we know Indigenous businesses are much more likely to employ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than non-Indigenous businesses.

- The Vocational Training and Employment Centre (VTEC) initiative has broken the cycle of training for training’s sake and has secured more than 7,600 jobs for Indigenous job seekers (as at 31 December 2017).

- The Government announced a $55.7 million Closing the Gap - Employment Services package in the 2017-18 Budget. As part of this package, jobactive is being boosted to deliver upfront intensive employment services to Indigenous job seekers.

The Australian Government is drawing on its regional network to strengthen its partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and stakeholders to develop and implement tailored and innovative solutions to the employment challenges facing Indigenous Australians.

Target

Halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within a decade (by 2018)

- Progress for this target is being masked by a change in remote employment programs. If this effect is removed, the employment rate rose by 4.2 percentage points over the past decade. Nonetheless, this target is not on track.

- The evolution of the Indigenous employment rate was in part driven by broader economic factors across the states and territories, with the employment rate falling in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory but stable or rising in the other states.

- Female Indigenous employment rates continue to improve, up from 39.0 per cent in 2006 (excluding CDEP) to 44.8 per cent in 2016. Participation rates have also risen, although this has been offset by Indigenous men increasingly dropping out of the labour market.

What the data tells us

National

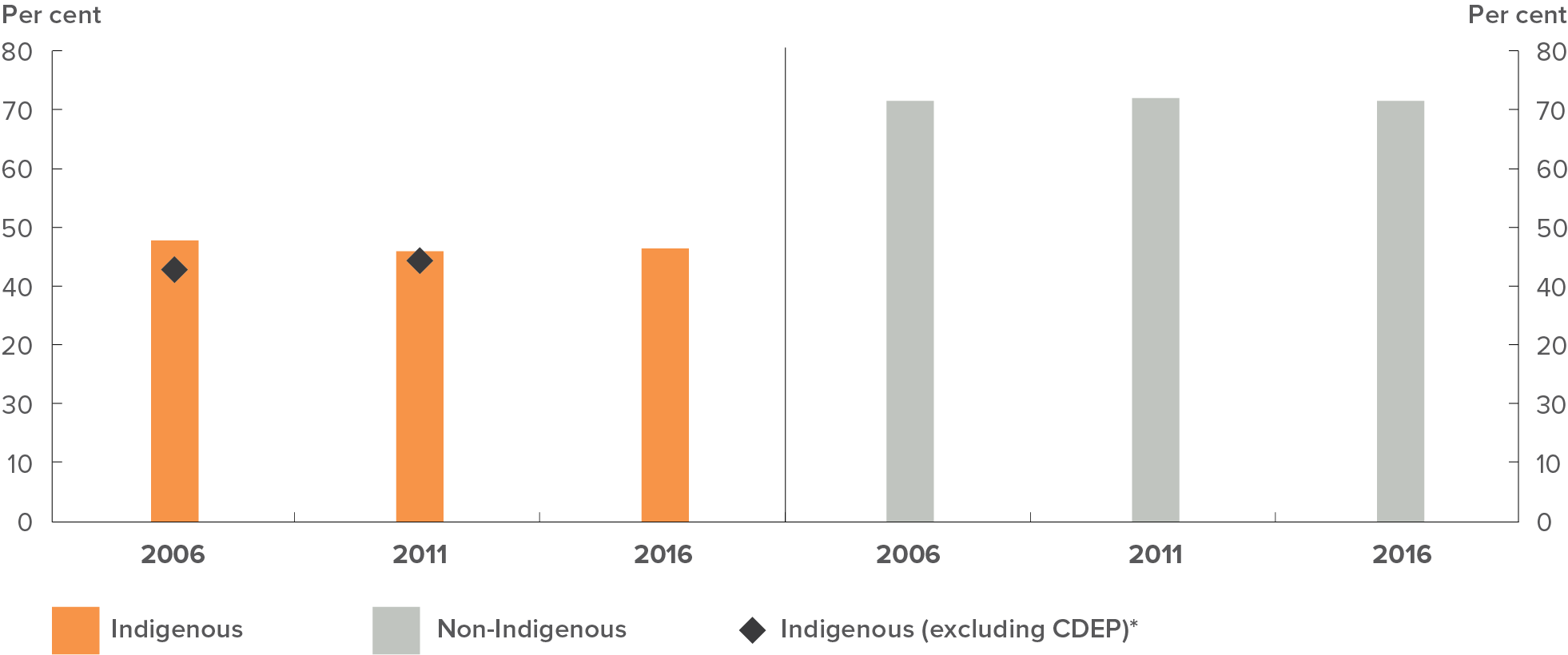

Progress against this target is measured using data on the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders of workforce age (15-64 years) who are employed (the employment-to-population ratio, or referred to here as the employment rate.[24]

The Indigenous employment rate fell over the past decade, from 48.0 per cent in 2006 to 46.6 per cent in 2016 (Figure 23). Over the same period, the non-Indigenous employment rate was broadly stable, around 72 per cent. As a result, the gap has widened by 1.5 percentage points to 25.2 percentage points over the past decade. Over the same period, the Indigenous unemployment rate rose slightly and the Indigenous participation rate was broadly steady (Box 1: Unemployment and participation rates).

The target to halve the gap in employment by 2018 is not on track.

Figure 23: Employment rates, 15–64 year-olds

Estimate of employment rate by removing CDEP participants from employment data. As the Census only asks Australians in remote areas about their CDEP status, it is likely to overestimate the excluding-CDEP employment rate. The CDEP program did not exist in 2016 so no estimate is shown.

Sources: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2006, 2011 and 2016

View the text alternative for Figure 23.

Nationally, the employment rate fell for Indigenous men between 2006 and 2016, but improved for women over the same period (Box 2: Employment by gender). At the same time, the employment rate has fallen for younger Indigenous people over the past decade, with 15-19 year-olds increasingly not in employment, education or training (Box 3: Youth not in employment, education or training).

The employment target is complicated by the cessation of the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP).[25] CDEP participants were previously classified as being employed, overstating employment outcomes. Job seekers who were eligible for CDEP are now supported into work-like activities through jobactive and Disability Employment Services (in urban and regional areas) and the Community Development Programme (in remote areas) and are no longer classified as being employed.[26]

Focusing on changes in the non-CDEP employment rate over time can provide a more accurate sense of labour market developments. If CDEP participants are excluded from those employed in 2006, the Indigenous employment rate falls by 5.6 percentage points to 42.4 per cent. Given that the 2016 employment rate was 46.6 per cent, this represents a 4.2 percentage point improvement over the past decade. However, this increase is likely to be an underestimate of the actual improvement in the non-CDEP employment rate, because the Census underestimates the number of CDEP participants.[27]

States and Territories

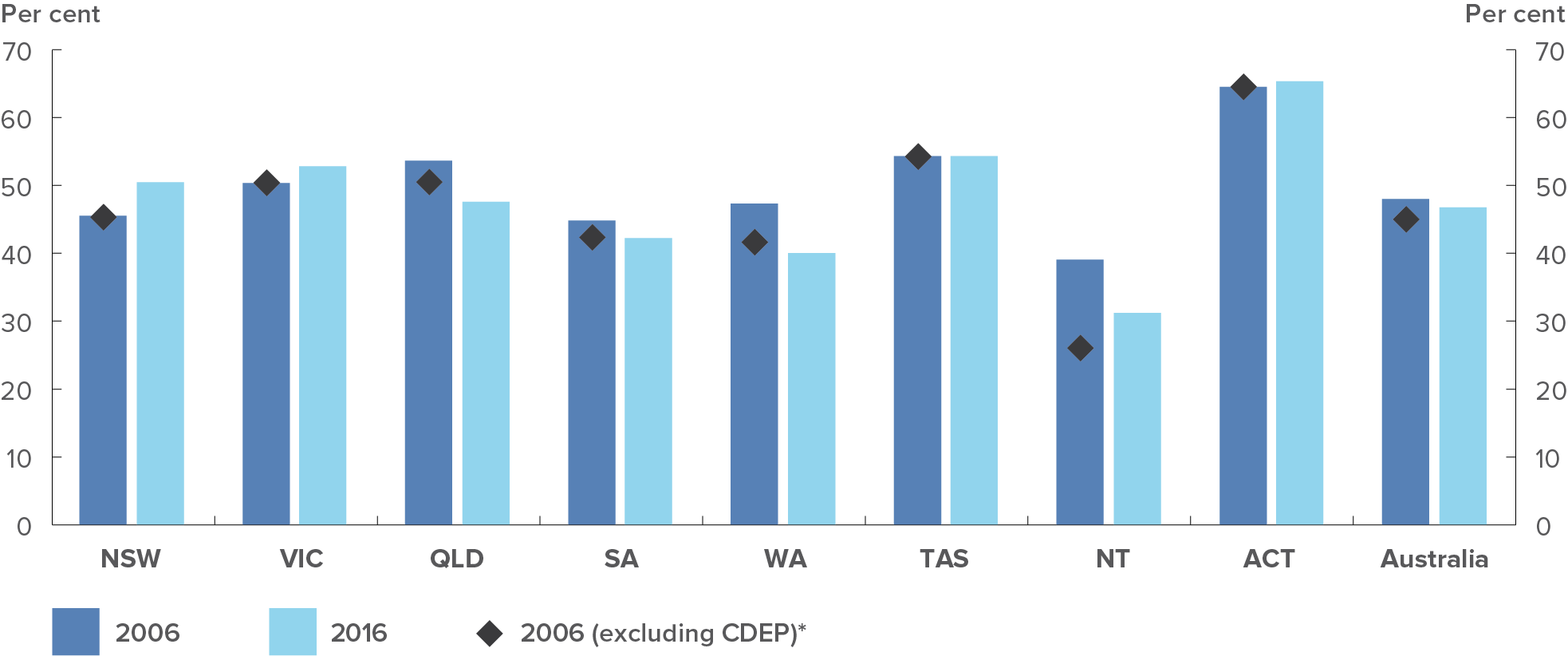

As was reported in the 2017 Closing the Gap report, New South Wales is the only jurisdiction currently on track to meet the employment target (based on the 2014-15 NATSISS). Using the more recent 2016 Census as a secondary source, the employment rate has improved somewhat in New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory between 2006 and 2016 (Figure 24).

The build-up of (and transition following) the mining investment boom has driven some significant disparity in economic conditions across the states over the past decade. This has flowed through to differences in employment growth, including for Indigenous Australians. For example, the Indigenous employment rate fell in the prominent mining states of Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory between 2006 and 2016.

Figure 24: Indigenous employment rates by jurisdiction, 15–64 year-olds

Estimate of employment rate by removing CDEP participants from employment data. As the Census only asks Australians in remote areas about their CDEP status, it is likely to overestimate the excluding-CDEP employment rate. The CDEP program did not exist in 2016 so no estimate is shown.

Sources: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2006 and 2016

View the text alternative for Figure 24.

Yet in spite of the broader decline in Indigenous employment rates in the mining states, the mining industry itself is employing significantly more Indigenous Australians than previously. These mining jobs are providing crucial opportunities for employment in regional areas.

For example, the mining industry currently employs 6,599 Indigenous Australians in 2016 (or 3.9 per cent of Indigenous employees), two-and-a-half times the number employed in 2006 (when it comprised 2.2 per cent of Indigenous employment). For comparison, non‑Indigenous mining employment grew by one-and-a-half times over the past decade.

The decline in Indigenous employment rates in mining states also partly reflects the transition from CDEP to CDP: the majority of the CDEP participants in 2006 were in Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland. For example, Census data shows that the Northern Territory’s Indigenous employment rate fell by 7.7 percentage points to 31.2 per cent in the ten years to 2016. However, excluding CDEP participants from the 2006 employment data indicates that the employment rate actually improved by at least 9.9 percentage points over the same period. This result is not surprising, especially as 21 per cent of the Northern Territory Indigenous working age population were CDEP participants in August 2006.

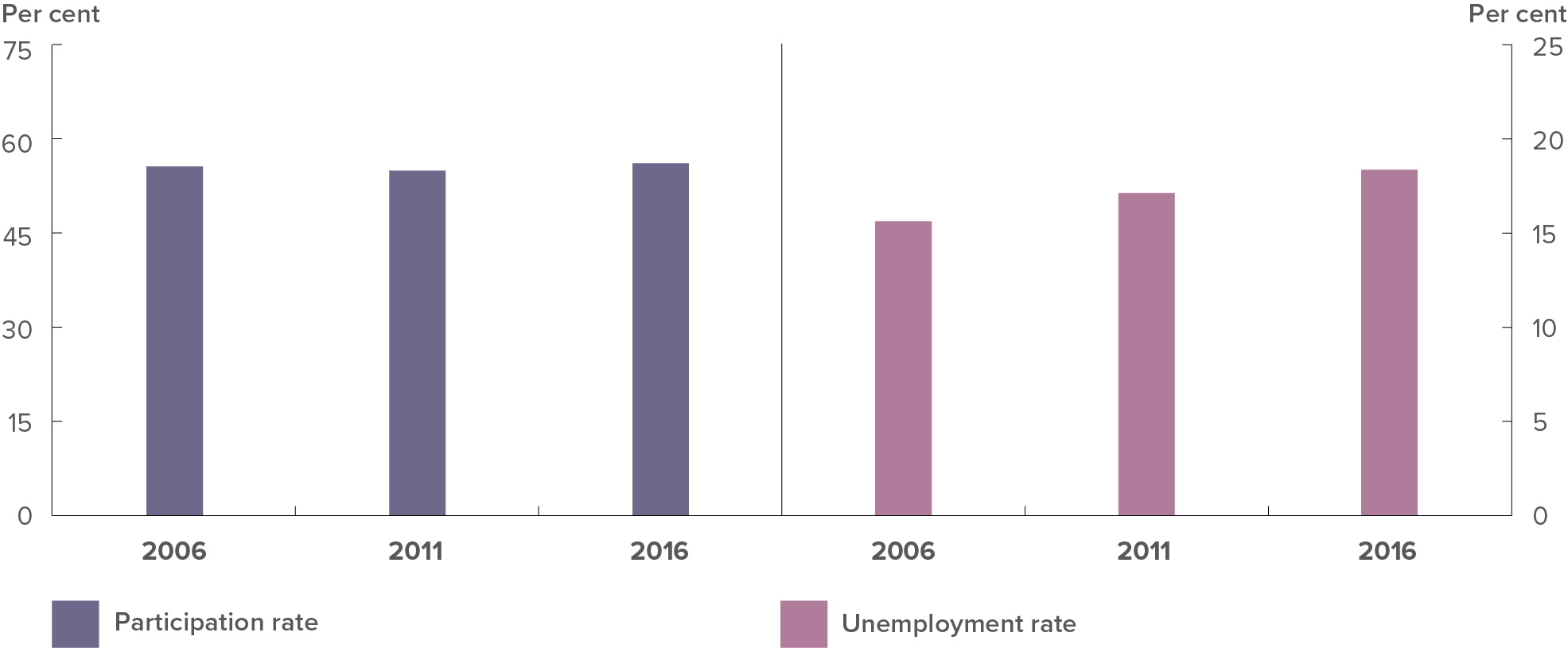

An alternative way to measure labour market outcomes is the unemployment rate, which measures the number of unemployed people as a proportion of the number of people who are in the labour force (that is, who are either employed or unemployed).[28]

In 2016, the unemployment rate for Indigenous people of working age was 18.4 per cent, 2.7 times the non-Indigenous unemployment rate (6.8 per cent). This is an increase from 15.6 per cent in 2006 and 17.2 per cent in 2011 (Figure 25).

It is also important to consider the participation rate, which compares the labour force to the total working age population. Often people may give up looking for work, perhaps because there are no jobs in their local area, and therefore drop out of the labour force. Others may drop out of the labour force due to caring responsibilities.

In 2016, the national Indigenous participation rate was 57.1 per cent, compared with 77 per cent for the non-Indigenous population and broadly steady relative to 2006 (56.8 per cent).

Figure 25: Indigenous participation rates and unemployment rates, 15–64 year-olds

Sources: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2006, 2011 and 2016

View the text alternative for Figure 25.

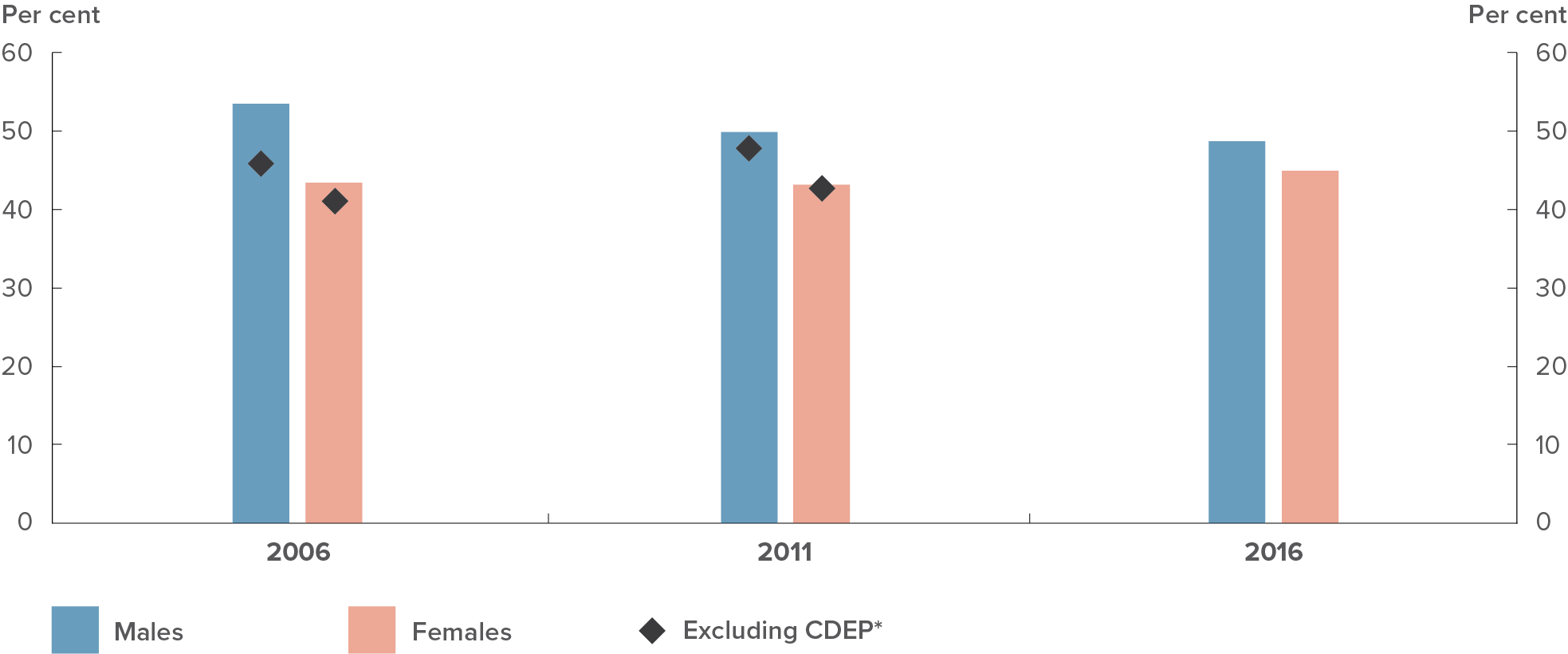

Differences in employment rates between Indigenous men and women have narrowed over the past decade (Figure 26), continuing a longer-term trend since the 1970s. Employment rates for Indigenous women have increased from 43.2 per cent in 2006 (39.0 per cent if excluding CDEP) to 44.8 per cent in 2016. On the other hand, the male Indigenous employment rate declined by 4.5 percentage points (but rose by 2.4 percentage points if excluding CDEP) between 2006 and 2016 (to 48.5 per cent).

In addition, Indigenous women are increasingly participating in the labour market, with their participation rate rising from 51.1 per cent in 2006 to 53.9 per cent in 2016. Indigenous men are instead dropping out of the labour market, with their participation rate falling by 2.6 percentage points (from 63.0 per cent to 60.4 per cent).

Figure 26: Indigenous employment rates by gender, 15–64 year-olds

Estimate of employment rate by removing CDEP participants from employment data. As the Census only asks Australians in remote areas about their CDEP status, it is likely to overestimate the excluding-CDEP employment rate. The CDEP program did not exist in 2016 so no estimate is shown.

Sources: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2006, 2011 and 2016

View the text alternative for Figure 26.

There are three important transitions that many young people will make as they approach adulthood. The first is transitioning through secondary school and completing Year 12 (or its equivalent). The second involves beginning post-school education and obtaining a qualification. The third transition is employment following education and embarking on a career path.

These are not necessarily easy transitions to make. During this period, the majority of young people spend at least one short spell not engaged in either the labour force or in education (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2016). However, ongoing disengagement has been linked to future unemployment, lower income and insecurity, placing these young people at risk of social and economic disadvantage and exclusion (Pech et al. 2009).

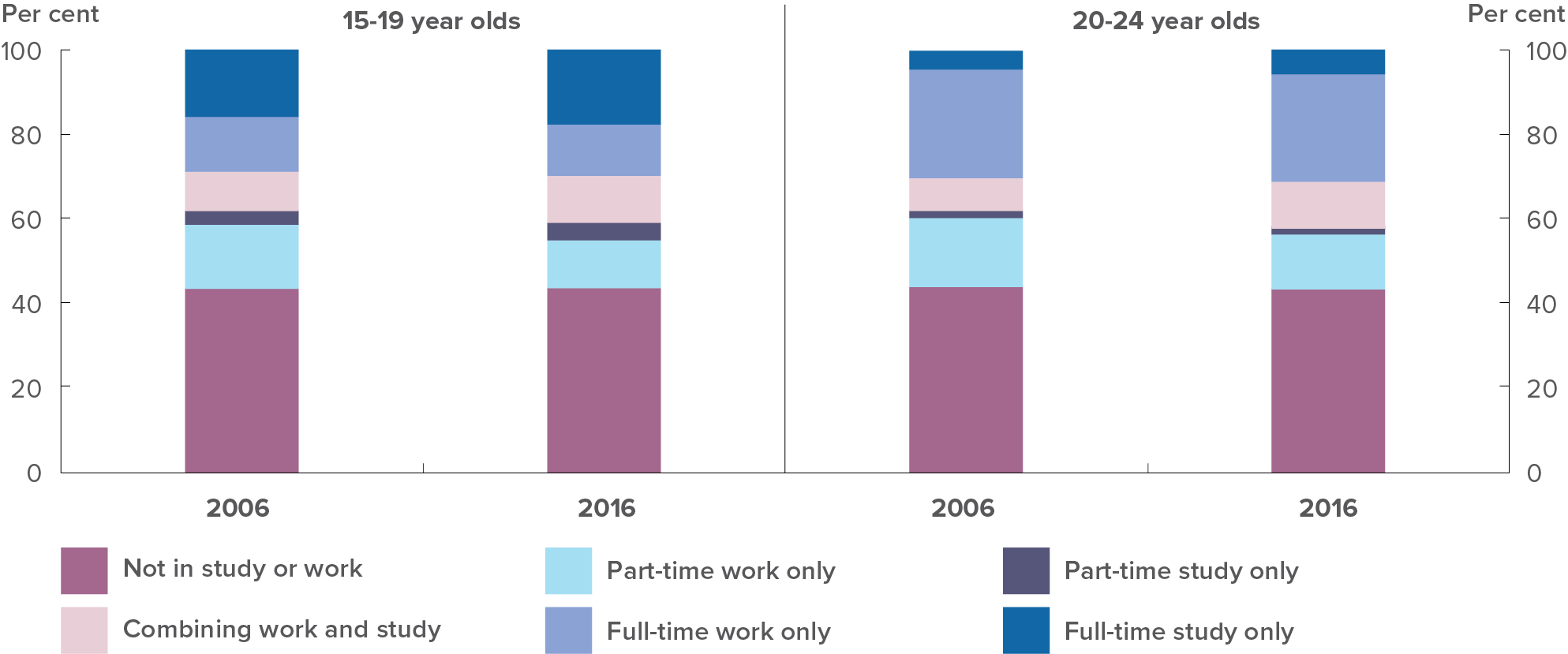

A significant proportion of young Indigenous people are not in employment, education or training (NEET). In 2016, 42.0 per cent of Indigenous 15-24 year-olds were NEET, with only one-third of these actively looking for work at the time (Figure 27).[29] These rates have deteriorated somewhat over the past decade: 41.1 per cent of Indigenous 15-24 year-olds were NEET in 2006. Most of this change is a result of an increase in Indigenous 15-19 year-olds who were NEET.

Figure 27: Indigenous participation rates in education and employment*

Chart excludes those away from work but not studying, as well as those where either education or work status could not be determined. No adjustment is made for CDEP status in 2006.

Sources: ABS Census of Population and Housing 2006 and 2016

View the text alternative for Figure 27.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) research indicates that the most important driver of NEET status in Australia is low educational attainment. Indeed, young Australians with Year 10 or below education are over three times more likely to be NEET as those with tertiary education (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2016).

However, there are other drivers of disengagement from the labour force and education. Slightly more young Indigenous women (43.3 per cent) were NEET in 2016 than their male peers (40.8 per cent). This gap is largely a result of childcare responsibilities – only 29.4 per cent of young Indigenous women who have never had a child were NEET in 2016.

Disability is another important reason for youth disengagement. According to the 2016 Census, 6.3 per cent of Indigenous 15-24 year-olds that were NEET had a profound or severe disability.[30] By contrast, only 2.4 per cent of their peers that were engaged in employment or education had a profound or severe disability.

Finally, young Indigenous people in remote communities often have greater barriers to starting a qualification or obtaining a job, due to scarce labour market opportunities. The OECD (2016) notes that only 28 per cent of Indigenous youths in Major Cities were NEET in 2011 (when data were last available), compared with 55 per cent in Very Remote areas.

Translating policy into action

Strengthening and growing the workforce

jobactive

jobactive is the Australian Government’s employment service for urban and regional centres. Around two-thirds of all Indigenous job seekers receiving Commonwealth employment assistance are supported through jobactive. Since the commencement of jobactive in July 2015, around 81,000 job placements have been achieved for Indigenous Australians.[31]

Community Development Programme

The Community Development Programme (CDP) is the Government’s remote employment and community development service, delivered across 60 regions to more than 1,000 communities. The CDP is a community-based program focused on helping job seekers to develop work-related skills and experience, address barriers, gain employment and make positive contributions to their communities.

Activities are community designed and delivered, and include a broad variety of projects such as work to renovate community buildings, landscaping, furniture production, helping in aged care facilities, training in hospitality, and preserving culture through traditional arts.

Since July 2015,[32] the program has supported remote jobseekers into around 21,600 jobs (including more than 15,700 jobs for Indigenous Australians). In the same period, the CDP supported jobseekers to stay in more than 7,000 jobs for at least 26 weeks (including more than 4,700 jobs for Indigenous Australians).

The 2017-18 Budget included an announcement that the Government was considering whether a new remote employment model should be designed and introduced. This was in recognition that more needs to be done to break the cycle of welfare dependency in remote Australia.

The Government’s vision is to design a new model that reflects ongoing feedback from stakeholders and communities on what they want. The Minister for Indigenous Affairs has stated his intention to bring back a ‘wage-based’ model for remote Australia, with greater local control, that provides local jobs for local people and is delivered by more Indigenous organisations. The vision is for a future program that combines the best parts from the CDP and past models such as the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP), with a new way of thinking to ensure the program not only maintains momentum but further improves outcomes for remote jobseekers and communities.

The Government commenced formal consultation on a new employment and participation model for remote communities with the release of a public discussion paper on 14 December 2017. This discussion paper explored how to grow the remote labour market, provide more incentives to jobseekers, give communities more control and greater decision-making, and improve the support available to jobseekers so they can move from welfare and into work. The paper outlined three potential options for discussion. These included an improved version of the current CDP model to provide more tailored support, a model based on the CDP Reform Bill introduced in 2015 and a new wage-based model, underpinned by three tiers of participation.

Vocational Training and Employment Centres

Vocational Training and Employment Centres (VTECs) are employment service providers that source guaranteed jobs, then assist jobseekers into these jobs and provide ‘wrap around’ support to achieve sustainable employment. As at 31 December 2017, with VTEC support, 7,617 Indigenous Australians had started in jobs and 4,320 jobseekers had achieved 26-week employment outcomes.

Employment Parity Initiative

The Employment Parity Initiative (EPI) works with large employers to increase Indigenous employment within their companies. As at 31 December 2017, the EPI had signed 12 large employers as parity partners, collectively committing to 7,465 jobs and placing 3,745 Indigenous Australians into jobs. Of those 1,881 had achieved 26-week employment outcomes.

Tailored Assistance Employment Grants

These grants can support either employers or third-party providers and generally target small to medium sized employers and employment opportunities not covered by other initiatives.

Grants include school-based apprenticeship and traineeship projects, and Indigenous cadetship projects that link undergraduates to employers who offer ongoing employment following completion of university.

Between 1 July 2014 and 31 December 2017, 311 agreements under the Tailored Assistance Employment Grants (including school-based traineeships and cadetships) were executed with a contracted value of more than $197 million (GST inclusive). During the same period, 13,249 employment places occurred for Indigenous Australians.

Prison to Work

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) released the Prison to Work report in December 2016 and noted jurisdictional Prison to Work Action Plans in June 2017.

The Australian Government is working with state and territory governments to address actions identified in the report to better support Indigenous prisoners moving from prison and into employment. States and territories are being regularly consulted and involved in joint actions to achieve these objectives. Jurisdictions will update COAG on progress every two years.

In the 2017-18 Budget the Government announced a $17.6 million initiative to assist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners access the support they need to better prepare them to find employment and reintegrate into the community upon their release from prison. The Time to Work Employment Service will commence in all states and territories in 2018.

Jobs for Indigenous rangers

The Government is investing $70 million a year to support Indigenous rangers. Together, the Indigenous rangers and Indigenous Protected Areas programs have created more than 2,500 jobs for First Australians (as at 30 June 2015). The majority of these jobs are located in regional and remote parts of the country.

The Indigenous ranger program supports Indigenous people to combine traditional knowledge with conservation training to protect and manage their land, sea and culture.

Building an Indigenous workforce in the public sector

In a commitment to increase Indigenous employment across the Commonwealth public sector, the Government announced a target of 3 per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation by 2018. At 30 June 2015, Indigenous representation across the Commonwealth public sector was 2.2 per cent. By 30 June 2017, Indigenous representation had increased to 2.7 per cent. A sustained effort will be required for the 3 per cent target to be met.

Disability Employment Services

This is a specialised employment support program for people whose disability is their main barrier to gaining employment. Around 10,800 Indigenous Australians participate in the program. Since it started in March 2010, the proportion of Indigenous jobseekers in the program has steadily increased from 4.5 per cent to 5.7 per cent (as of 31 August 2017). The number of employment outcomes has increased at a similar rate. Around 6.2 per cent of all participants that maintain employment for 13 weeks are Indigenous Australians (from 3.5 per cent in 2010), and for 26 weeks of employment the number has risen from 3.5 per cent in 2010 to almost 6 per cent.

ParentsNext

This program helps parents receiving a Parenting Payment in 10 locations identify their education and employment goals, develop a pathway to achieve those goals, and link into activities and services in the local community.

From 1 July 2018, there will be a $263 million national expansion of this program including a second stream delivering more intensive ParentsNext in the existing 10 locations and a further 20 locations, where there is a high proportion of Parenting Payment recipients who are Indigenous.

Transition to Work

The Transition to Work service has been expanded (from 1 January 2018) to include all Indigenous Australians aged 15‑21 who are not in work or study, including those with a Year 12 Certificate. The service provides intensive, pre-employment support to improve the work-readiness of young people and help them into work (including apprenticeships and traineeships) or education. It is expected that around 4,600 extra Indigenous young people per year will benefit from the service.

Local solutions

Leading by example in Ntaria

Bronwyn Lankin and Freddy Peipei, successfully transitioned from participating in the CDP to being employed as Assistant Supervisors at Indigenous CDP provider, Tjuwanpa Outstation Resource Centre Aboriginal Corporation.

Find out more about Leading by example in Ntaria.

More local solutions are available on the resources page.

[24] The main data source used to assess progress against this target is the ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) and Social Survey (NATSISS). Data from the 2014-15 NATSISS published in last year’s report showed that this target was not on track. While not directly comparable with the survey data, the ABS Census provides a secondary source of data for this target. New data for 2016 were released in October 2017, and the target is still not on track.

[25] CDEP was a Commonwealth employment program in which participants were paid CDEP wages (derived from income support) to participate in activity or training.

[26] As CDEP was wound down and participation declined, many of these individuals transferred across to other employment services, where they received income support and were then counted as unemployed.

[27] The ABS Census only asks people who were counted using an Interviewer Household Form about their participation in CDEP. In particular, this form is primarily used for discrete Indigenous communities. To compare, 32,782 Indigenous people were registered as CDEP participants as at 8 August 2006 (the date of the 2006 Census); however, only 14,497 people were counted as CDEP participants in the Census itself.

[28] Note that there are differences between the Census and the ABS Labour Force Survey. For more information, see Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017b).

[29] It is important to note that the Census only captures NEET status at a point in time, and so does not indicate the length of time an individual is disengaged from the labour force or education.

[30] The ABS defines a person with a profound or severe disability as requiring assistance with one or more of three core activity areas (self-care, mobility and communication) because of a disability, long-term health condition (lasting six months or more) or old age

[31] As at 31 December 2017.

[32] Data is as at 31 December 2017.