Taking a holistic approach

"Without good nutrition infants cannot thrive, children cannot succeed at school and employment opportunities are diminished. Remote community members want their children to grow up healthy but face barriers to accessing nutritious, affordable food. Communities are driving solutions and are active partners in our practical, community-based program. They recognise the importance of programs that are long-term and build capacity and confidence." - Chair EON Foundation, Caroline de Mori

Jason Bartlett decided to share his story to help other men take responsibility for their health. 'Passing on Wisdom: Jason's Diabetes Story' documents his final days before he died in June 2017. Here, Jason's widow, Jamiee Bartlett, holds a photograph of her husband, left to right, with Dr Sandra Thompson, from the WA Centre for Rural Health, Minister for Indigenous Health, and Aged Care Ken Wyatt AM, and Adrian Bartlett (both cousins of Jason), his brother Phil Bartlett and WACRH's Lenny Papertalk.

A holistic approach to improving health outcomes

Access to health services is fundamental to the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The provision of primary health care and specialist services for First Australians is playing an increasing role in the prevention and management of chronic disease.

True and lasting gains are made when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and individuals are front and centre of decision making and driving outcomes in their choices in respect to health care.

We must also continue to focus on addressing the social and cultural determinants of health in order to further improve health and wellbeing.

The Government is investing broadly and carefully to lift outcomes in these areas, which in turn will help enhance the health of our First Nations people.

As part of this, the Government is investing in programs that increase food security and boost nutrition levels in remote Indigenous communities. Ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are able to access heathy, affordable food is a key to better health.

Target

Close the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within a generation (by 2031)

- Between the periods 2005-2007 and 2010-2012 there was a small reduction in the life expectancy gap of 0.8 years for males and 0.1 years for females.

- Over the longer term, Indigenous mortality rates have declined significantly by 14 per cent since 1998. However, there has been no improvement since the 2006 baseline and the target is not on track to be met.

- There have been significant improvements in the Indigenous mortality rate from chronic diseases, particularly from circulatory diseases (the leading cause of death) since 1998. However, Indigenous mortality rates from cancer (second leading cause of death) are rising and the gap is widening.

- There have been improvements in early detection and management of chronic disease and reductions in smoking which should contribute to long-term improvements in the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

What the data tells us

National

While the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is gradually improving, the target to close the gap in life expectancy by 2031 is not on track. Progress will have to gather pace if the target is to be met in 2031. The target is measured by estimates of life expectancy at birth, which are available every five years.[33]

The most recent Indigenous life expectancy estimates were published in 2013 and showed Indigenous males born between 2010 and 2012 have a life expectancy of 69.1 years (10.6 years less than non-Indigenous males) while females have an estimated life expectancy of 73.7 years (9.5 years less than non-Indigenous females) (Table 4 and Box 1: Life expectancy by age).

Between the periods 2005-2007 and 2010-2012, the estimated life expectancy at birth for Indigenous males increased by around 0.3 years per year, and by around 0.1 years per year for Indigenous females – this led to a small reduction in the gap of 0.8 years for males and 0.1 years for females. To meet the target of closing the gap by 2031, Indigenous life expectancy needs to increase by around 0.6 to 0.8 years per year.

Table 4: Life expectancy at birth

| Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Gap (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| 2005-2007 | 67.5 | 73.1 | 78.9 | 82.6 | 11.4 | 9.6 |

| 2010-2012 | 69.1 | 73.7 | 79.7 | 83.1 | 10.6 | 9.5 |

Source: ABS, 2013, Life tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2010–2012. ABS Cat. No. 3302.0.55.003.

View the text alternative for Table 4.

Mortality

While official Indigenous life expectancy estimates are only available every five years, progress for this target is tracked using annual mortality rates.[34]

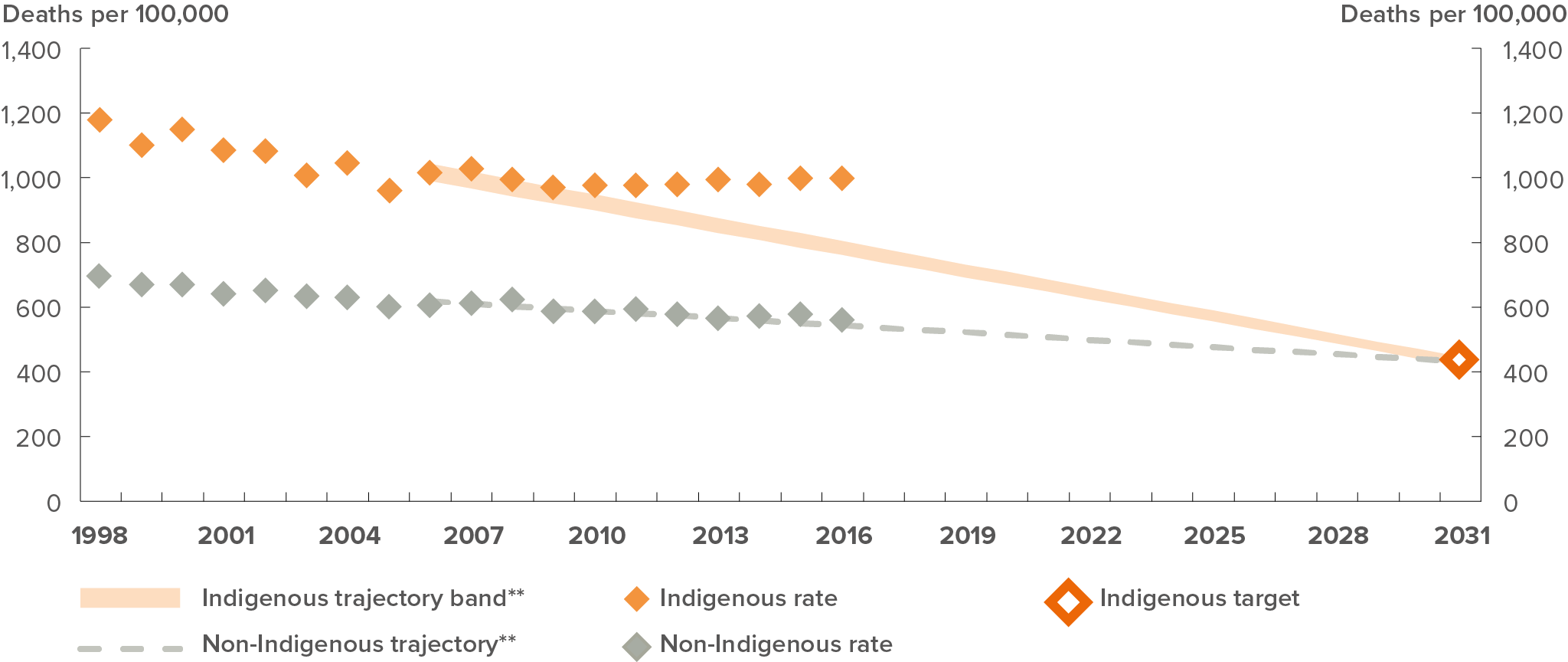

Between 1998 and 2016, the overall Indigenous mortality rate declined significantly, by 14 per cent.[35] Non-Indigenous death rates also declined over this period, and the gap has narrowed by around nine per cent (not statistically significant). Despite these long-term improvements, there has been no significant change in the Indigenous mortality rate between 2006 (baseline) and 2016 and the current Indigenous mortality rate is not on track to meet the target (Figure 28).[36] Mortality rates are also continuing to decline for non-Indigenous Australians, which explains why the gap has not narrowed since 2006.

* Indigenous mortality data for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory only and is age standardised.

** The non-Indigenous trajectory is based on the non-Indigenous trend between 1998 and 2012, from which the Indigenous trajectory was derived.

Sources: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

View the text alternative for Figure 28.

Leading causes of Indigenous mortality

In 2016, nearly three in four (71 per cent) Indigenous deaths were from chronic diseases (including circulatory disease, cancer, diabetes and respiratory disease). These diseases accounted for 79 per cent of the gap in mortality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

While it is undeniable that progress needs to be faster, there have been consistent, gradual improvements in health outcomes impacting on life expectancy.

There have been reductions in smoking (Box 2: Falling smoking rates among Indigenous Australians and impact on mortality), improved early detection and management of chronic disease, and improvements in social determinants of health such as educational attainment.

Between 1998 and 2016, the decline in Indigenous mortality rates was the strongest for circulatory disease. Indigenous mortality rates from circulatory diseases reduced by about 45 per cent, and the gap narrowed by 43 per cent. Since 2006, there has been a significant decrease of 23 per cent in Indigenous circulatory disease mortality rates.

However, cancer mortality rates are rising for Indigenous Australians and the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians’ cancer mortality rates is widening. Between 1998 and 2016, there was a significant increase by 23 per cent in the cancer mortality rate for Indigenous Australians while the rate has declined significantly by 14 per cent for non-Indigenous Australians.

Some health interventions under Closing the Gap, especially population health interventions, have a long lead time before measurable impacts are seen. For instance, smoking rates may take five years to impact on heart disease and up to 30 years to impact on cancer deaths. Improvements in educational attainment will take 20 to 30 years to impact on early deaths from chronic disease in the middle years when most deaths for Indigenous Australians occur (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2017).

States and territories

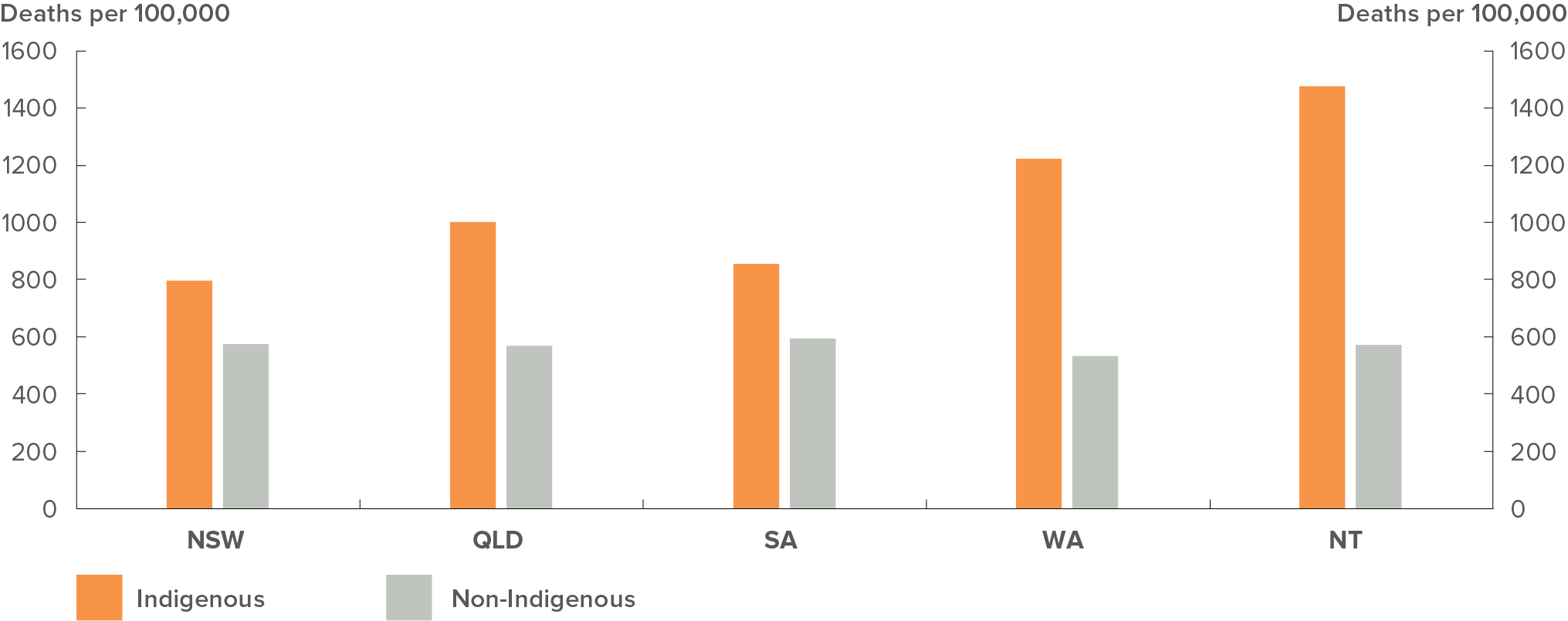

Over the period 2012 to 2016,[37] Indigenous mortality rates varied across the jurisdictions (Figure 29). The Northern Territory had the highest Indigenous mortality rate (1,478 per 100,000 population) as well as the largest gap with non-Indigenous Australians, followed by Western Australia (1,225 per 100,000).

Only Western Australia has seen a significant decline in Indigenous mortality rates rate since 2006 – a decline of 20.4 per cent, leading to a narrowing of the gap by 27.2 per cent.

Of the four jurisdictions (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory) that have agreed trajectories for this target, none were on track in 2016 to meet the target.

Figure 29: Mortality rates by jurisdiction, 2012-2016

Sources: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

View the text alternative for Figure 29.

Life expectancy at birth provides an estimate of the average number of years a group of newborns (in the period 2010-2012) could live if current death rates remain unchanged. The ABS also published estimates of life expectancies at other age groups for the period 2010-2012. (Table 5).

Table 5: Life expectancies at selected ages: 2010-2012

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Gap (years) | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Gap (years) |

| 0 | 69.1 | 79.7 | -10.6 | 73.7 | 83.1 | -9.5 |

| 1 | 68.7 | 79.0 | -10.3 | 73.2 | 82.4 | -9.2 |

| 5 | 64.9 | 75.1 | -10.2 | 69.3 | 78.5 | -9.2 |

| 25 | 45.7 | 55.5 | -9.8 | 49.8 | 58.7 | -8.9 |

| 50 | 24.5 | 31.7 | -7.2 | 27.2 | 34.4 | -7.1 |

| 65 | 13.9 | 18.6 | -4.7 | 15.8 | 20.6 | -4.8 |

| 85 | 4.2 | 4.6 | -0.4 | 4.4 | 4.8 | -0.3 |

Source: ABS, 2013 Life tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2010–2012. ABS Cat. No. 3302.0.55.003.

View the text alternative for Table 5.

Indigenous life expectancy for those aged 65 years during 2010-2012 is 13.9 years for males and 15.8 years for females, a gap of less than five years.

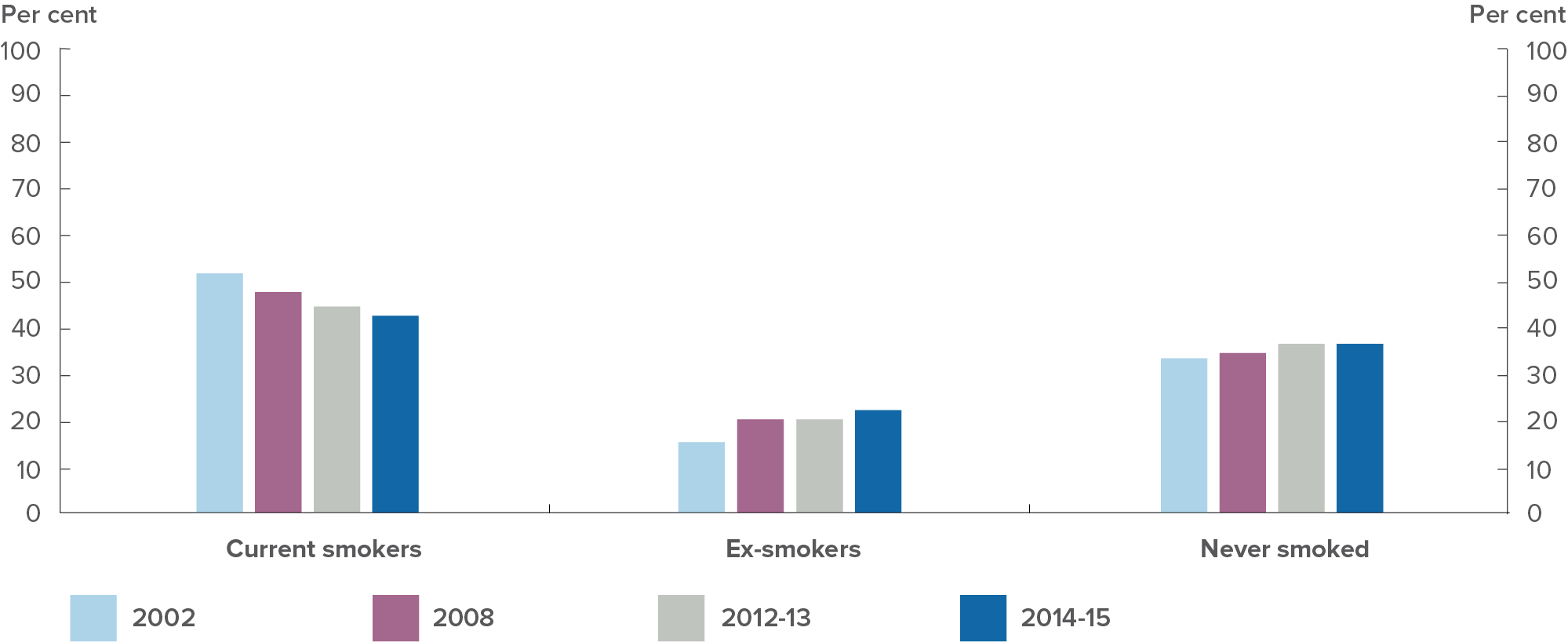

Smoking, and tobacco use, is the leading contributor to the burden of disease among Indigenous Australians, accounting for 12 per cent of the total burden in 2011 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016). Smoking prevalence for Indigenous Australians (aged 15 years and over) has declined significantly (a reduction of 9 percentage points) between 2002 and 2014-15, from 51 to 42 per cent (Figure 30). While some health effects from smoking are immediate, there is a long lag, up to three decades, between changes in smoking rates and impacts upon many smoking-related diseases. As such, many of the health benefits and improvements in mortality will not be seen for some time.

This decline in smoking prevalence means an increase in the number of Indigenous Australians who have quit smoking (ex-smokers) and in the number who have chosen to never take up smoking (never smoked). From 2002 to 2014-15, the proportion of Indigenous ex-smokers (15 years and over) increased from 15 per cent to 22 per cent (around 99,500 people), and the proportion who never smoked increased from 33 per cent to 36 per cent (around 158,200 people) (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2017).

Figure 30: Smoking trends for Indigenous Australians

Source: AHMAC, 2017

View the text alternative for Figure 30.

Most of the decline in Indigenous smoking prevalence has been in non-remote areas (from 50 per cent in 2002 to 39 per cent in 2014-15) while smoking rates in remote areas have remained relatively stable (55 per cent in 2002 and 52 per cent in 2014-15) (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2017).

Quitting smoking earlier in life (or not smoking) provides the greatest expected health benefits. Encouragingly the largest decreases in smoking rates have been in the younger age groups: from 58 per cent in 2002 to 41 per cent in 2014-15 for 18-24 year-olds; and from 33 per cent to 17 per cent for 15-17 year-olds (Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council 2017). Given the younger age profile of the Indigenous population, the decline in smoking prevalence among younger adults has significant potential for further population level decline in smoking and related health benefits.

Decreases in Indigenous smoking prevalence and smoking initiation (smoking rates for 15‑17 year‑olds) have been faster for the period 2008 to 2014-15 than for the period 1994 to 2004‑05.This suggests that smoking cessation measures targeting Indigenous Australians, implemented since 2008, are having an impact (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017c).

The significant decline in smoking prevalence among Indigenous Australians will provide health benefits over time. For example, the burden of tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is likely to continue to decline in the short term. However, because of the long lag time between smoking behaviour and the onset of tobacco-related cancer mortality, smoking related deaths are likely to continue to rise over the next decade, before peaking, due to the legacy from when smoking prevalence was at its peak (Lovett et al. 2017).

These findings emphasize the need to sustain effective and culturally appropriate smoking prevention/cessation programs to keep downward pressure on smoking rates – especially among subgroups of Indigenous Australians with relatively stable smoking rates (remote and older age groups). This will assist in accelerating decline in smoking prevalence, which, in turn, will lead to greater health gains over the short and the long term.

Translating policy into action

Primary health care

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-23 sets out the Australian Government’s vision, principles, priorities and strategies to deliver better health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. It provides the policy framework.

An implementation plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-23 outlines the actions to be taken by the Australian Government, the Aboriginal community controlled health sector, and other key stakeholders to give effect to the vision, principles, priorities and strategies set out in the health plan.

Significant gains have been achieved by reforming the health system, addressing behavioural factors that influence health outcomes and improving investment across the life course by targeting the leading causes of death.

Funding of $3.6 billion over four years (from 2017-18) is being provided through the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme to implement Indigenous-specific measures outlined in the health implementation plan. Initiatives under the implementation plan are also delivered through mainstream programs such as the Medicare Benefits Schedule, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, public hospital and aged care facilities. Progress under the plan is measured against 20 goals that were developed to complement the existing COAG Closing the Gap targets, and focus on prevention and early intervention across the life course.

Primary Health Networks are working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations to identify, design and commission culturally-appropriate services to meet the needs of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Under the 2008 National Partnership Agreement (NPA) on Closing the Gap in Indigenous Health Outcomes, the Australian Government delivered the Indigenous Chronic Disease Package (ICDP), worth $805.5 million over four years (2009-2013) to tackle chronic disease among Indigenous Australians. The ICDP focused on tackling the risk factors of chronic disease, providing primary health care services that deliver, and improving patient journeys by fixing gaps in the health system. A 2012-13 evaluation of the ICDP found that it produced substantial increases in access to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The Closing the Gap PBS co-payment measure, implemented 1 July 2010, subsidises medication for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with existing chronic disease, or who are at risk of chronic disease. This measure is aimed at improving access and use of medications. In 2015-16, 4.8 million scripts were issued under the Closing the Gap co-payment measure, assisting more than 277,000 patients.

Partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

From July 2017, the Government has been supporting the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health (ACCH) sector through a new Network Funding Agreement (NFA) with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). The NFA was developed in consultation with the ACCH sector and takes a streamlined, outcomes-focused approach to funding a national network of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sector Support Organisations under the Indigenous Australians Health Programme.

Supporting Indigenous Australians with disabilities

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience disability at approximately twice the rate of other Australians. Given this, it is vital that the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) continues to work with Indigenous communities in metropolitan, regional and remote communities to ensure they have appropriate access to the scheme.

More than 5,500 people who identify as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander are currently being assisted by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). It is expected the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being supported by the NDIS will grow as the scheme continues to be rolled out.

The NDIA is engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through a dedicated Indigenous engagement strategy, a rural and remote strategy and the agency’s Reconciliation Action Plan.

School nutrition projects in the Northern Territory

The Australian Government allocated $24 million for school nutrition projects in the Northern Territory over three years until mid-2018 for school nutrition activities. These activities are providing nutritious meals aimed at increasing Indigenous attendance and engagement. School nutrition projects operate in 72 sites in 63 communities and provide meals to around 5,400 children per school day. In addition, school nutrition projects aim to increase local Indigenous employment, employing around 230 staff of which around 168 are local Aboriginal people.

Social and emotional wellbeing

Following the National Apology Australia’s Indigenous Peoples, and as part of the Council of Australian Governments’ Closing the Gap strategy, funding is provided to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation to address the harmful legacy of colonisation, in particular the history of child removal that has affected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The work of the Healing Foundation and other key stakeholders has been significant in focusing attention on the need for trauma-informed practice and services.

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-23 published in October 2017 provides a dedicated focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing and mental health. It sets out a comprehensive and culturally appropriate stepped care model that is equally applicable to both Indigenous specific and mainstream health services. It will guide and support Indigenous mental health policy and practice over the next five years and is an important resource for policy makers, advocates, service providers, clients, consumers and researchers.

It is designed to complement the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan and contribute to the vision of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2012-2023. It therefore forms an essential component of the national response to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health.

Social and Emotional Wellbeing support services are funded to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with priority given to members of the Stolen Generations and their families. Activities include counselling, family tracing and reunions, and a range of healing activities.

National Indigenous Critical Response Service

The Australian Government is investing $10 million in the National Indigenous Critical Response Service (NICRS) to provide support to individuals, families and communities in response to suicides or other critical incidents involving deaths. This service commenced in 2017 and is being progressively rolled out across Australia over three years.

The NICRS helps affected individuals and families by assessing their needs and providing practical and social support, including by facilitating connections with support services as needed and monitoring through-care over time, referring on to social, health or other services where appropriate.

The service helps to coordinate services in a culturally appropriate way and is also strengthening community capacity and resilience in some high-risk communities.

Aged care

An Aged Care Diversity Framework has been developed for all older people and is intended to assist providers, and enhance the aged care sector’s capacity to better meet the diverse characteristics and life experiences of older people, thereby ensuring inclusive aged care services. Under the framework, an action plan is being developed to address the specific barriers and challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Encouraging healthy lifestyle choices

Indigenous sports

Through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, the Australian Government has committed more than $135 million to support 151 activities that use sport as a tool to achieve Closing the Gap outcomes. This investment includes activities that increase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s participation in sport and recreation, use sport and recreation to improve wellbeing and resilience, improve educational attendance and attainment, engage youth, develop or upgrade infrastructure facilities and help to provide employment and training opportunities.

Outback stores

Outback Stores, a Commonwealth-owned company, was established in 2006 in recognition of the hardship faced by many residents in remote areas in accessing regular, quality, affordable and healthy food. It has a mandate to improve access to affordable healthy food and provide employment for remote Indigenous communities through the provision of quality retail management services for community stores.

Outback Stores manages 36 community stores throughout the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia to ensure food security in these communities. In 2016-17, health and employment strategies implemented by Outback Stores resulted in:

- a reduction of full sugar drink sales which resulted in a reduction of 11.5 tonnes less sugar consumed;

- 406 tonnes of fresh fruit and vegetables sold in communities in which Outback Stores operates; and

- 298 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being employed in the stores that Outback Stores manages, which is almost 80 per cent of all team members employed in stores.

Support for Northern Territory stores

The Australian Government is helping to improve the health of people living in remote Northern Territory communities through the Northern Territory Community Stores Licensing Scheme that is making healthy food and drinks more accessible for local residents. There are currently more than 100 licensed stores operating in the Northern Territory. The Government is also supporting community stores through the Aboriginals Benefit Account, which has provided $55.8 million to support 18 stores over the last five years in the NT.

Strategy to reduce sugar consumption through remote community stores

The Australian Government has developed a strategy to reduce the sales of highly sugared products sold in stores in remote Indigenous communities. The store is often the main - or only - source of food and drinks in remote communities, so a reduction the amount of sugared products sold in the store is an effective way of reducing the amount sugar products consumed. The strategy is being implemented in stages through until June 2020, focusing on sugary drinks and expanding to other high-sugar products such as confectionary.

Reducing substance misuse and harm

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Drug Strategy 2014-2019 provides a framework for action to minimise the harms to individuals, families and communities from alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. The strategy guides governments, communities, service providers and individuals to identify key issues and priority areas for action.

Through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, the Australian Government funds more than 80 organisations across the country to deliver Indigenous‑specific alcohol and other drug treatment services. Providers aim to reduce substance misuse by providing a range of services that can include early intervention, treatment and prevention, residential rehabilitation, transitional aftercare and outreach support. Elements can include access to sobering up shelters, advocacy and referral, counselling, case management, youth-specific support, education and health promotion, cultural and capacity building, and life skills support.

Overall funding for alcohol and other drug treatment services under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy in 2017-18 is around $70 million. This is in addition to alcohol and other drug services, including Indigenous-specific services, funded through the Health portfolio.

Approximately 32,700 clients received at least one type of substance-use service funded under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, with around 170,400 instances of care provided, based data from the 2015-16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Organisations Online Services Report.

In recognition of the acute need in the Northern Territory, the Australian Government is investing around $91.5 million over seven years (from 2015-16) to tackle alcohol misuse through the National Partnership on Northern Territory Remote Aboriginal Investment (NP NTRAI). This includes around $13 million for Alcohol Action Initiatives (AAIs), which are community-developed activities to tackle alcohol misuse and harm. Around $14 million is also provided under the NP NTRAI for an AAI workforce to engage directly with communities to ensure activities are evidence-based and to strengthen community capacity and governance to help communities proactively manage alcohol concerns. In addition, around $31 million has been provided under the NP NTRAI to support a Remote Alcohol and Other Drug Workforce to provide alcohol and drug support and education, interventions, and referrals for community members.

Reducing petrol sniffing

In some remote communities, petrol sniffing was having a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. This led to communities and governments working together to develop a solution. Low aromatic fuel was first made available in communities in Central Australia and Western Australia in 2005 and has been highly successful in reducing rates of petrol sniffing. The fuel is now available in more than 175 fuel outlets in Queensland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia.

Immunisation

Immunisation has been a specific focus globally over the past decade, particularly for organisations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organisation. Ensuring high immunisation coverage rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is an important contribution to Closing the Gap in Indigenous health outcomes.

Australia’s National Immunisation Programme, a collaborative program involving the Australian Government and the state and territory governments, was established in 1997 to reduce the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases by improving national immunisation coverage rates. Since 2013, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander five year-old cohort coverage rate has exceeded the immunisation coverage rate of all children in the same age cohort.

The NIP provides free vaccines against 17 vaccine-preventable diseases to eligible groups including children, the elderly, pregnant women and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Since the introduction of the NIP in 1997, Australia has lifted its national childhood immunisation rates to more than 90 per cent from a reported low of 53 per cent in the late 1980s.

To support and increase vaccination rates, the NIP was expanded on 1 July 2017 to provide ongoing free catch-up vaccines equivalent to those received in childhood for all young people up to the age of 19 years, and refugee and humanitarian entrants of any age.

To further support vaccination uptake, a three-year childhood immunisation education campaign was launched by the Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, on 13 August 2017.

Better identifying Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Action Plan

The Australian Government provided funding of $9.2 million over four years (2013-14 to 2016-17) towards the FASD Action Plan. To build on this early investment, the Government announced in the 2016 Budget a $10.5 million investment in initiatives to reduce the impact of FASD in the Australian community.

A national FASD Strategic Action Plan is currently being developed. This will provide an approach for all levels of government, organisations and individuals regarding strategies that target the reduction of alcohol-related harms relating to FASD. The strategy will aims to reduce the prevalence of FASD in Australia and provide advice and coordination on the support available to those affected by the disorder.

Reducing smoking

Further reducing the smoking prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can be expected to provide a meaningful contribution to the Government’s efforts to halving the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five. In particular, successful efforts to reduce smoking prevalence among pregnant Indigenous women and their families, and their exposure to tobacco smoke are likely to be particularly important. In this regard, there is strong evidence that tobacco smoking and smoke exposure during pregnancy and childhood cause considerable childhood morbidity and mortality (Mund et al. 2013).

Progress in this area will continue to require a combination of population-level strategies and approaches in tobacco control (such as measures to further reduce the affordability of tobacco products and comprehensive smoke-free legislation and policies), as well as initiatives targeted towards Indigenous Australians such as the Government’s Tackling Indigenous Smoking program.

Improving the quality of remote housing

Good quality housing underpins all of the Closing the Gap targets in health, education and employment, as well as community safety.

The Australian Government has invested $5.5 billion over the past 10 years to improve the quality of housing in remote communities. This has seen percentage of houses that are overcrowded drop from 52 per cent to 37 per cent. Tenants now have rights and responsibilities they didn’t previously have and the system of housing operates as a genuine public housing system.

Local solutions

EON thriving communities leading to healthier lives

Students from the Ngalangangpum School tending to the school garden with EON Foundation staff at Warmun in the East Kimberley.

Find out more about EON thriving communities leading to healthier lives.

More local solutions are available on the resources page.

[33] The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publishes life tables and calculates life expectancy for the Australian population and for some groups of the population. These measures are based on three years of data to reduce the effect of variations in death rates from year to year. Updated estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectancy are due to be published by the ABS in 2018.

[34] Indigenous mortality data includes New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory only, which are the jurisdictions considered to have adequate levels of Indigenous identification suitable to publish.

[35] As the Indigenous population is much younger, comparisons of mortality rates with non-Indigenous Australians are made after adjusting for the different age structures of the two populations.

[36] From 2015, deaths data provided by the Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages includes Medical Certificate of Cause of Death information, resulting in an increase in the number of deaths identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander in Queensland.

[37] Due to the small numbers involved, five years of data is combined so that differences between the jurisdictions can be shown