1.01 Low birthweight

Page content

Why is it important?

Low birthweight (newborns weighing less than 2,500 grams) is associated with premature birth or restricted fetal growth. Low birthweight infants are at a greater risk of dying during their first year of life (see measure 1.21), and are prone to ill-health in childhood and the development of chronic disease as adults, including cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, kidney disease and Type 2 diabetes (OECD, 2011; Scott, 2014; Arnold, L et al, 2016; Luyckx et al, 2013; Zhang, Z et al, 2014; Hoy, W & Nicol, 2010; White, A et al, 2010).

Risk factors for low birthweight include maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy (see measure 2.21); poor antenatal care (see measure 3.01); the weight, age and nutritional status of the mother; the number of babies previously born to the mother; illness during pregnancy; pre-existing high blood pressure and diabetes; multiple births; socio-economic disadvantage; and experiencing three or more social health issues during pregnancy (AIHW, 2011a; Eades, S et al, 2008; ABS & AIHW, 2008; Sayers & Powers, 1997; Brown, SJ et al, 2016b; Khalidi et al, 2012).

Findings

National perinatal data for 2014 shows that low birthweight was almost twice as common among live born babies born to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers as among those born to a non-Indigenous mother (11.8% compared with 6.2%). After excluding multiple births, the proportions were 10.5% and 4.7% respectively. The low birthweight rate for Indigenous babies (i.e. based on the Indigenous status of the baby) was 9.6% (and 4.6% for non-Indigenous babies).

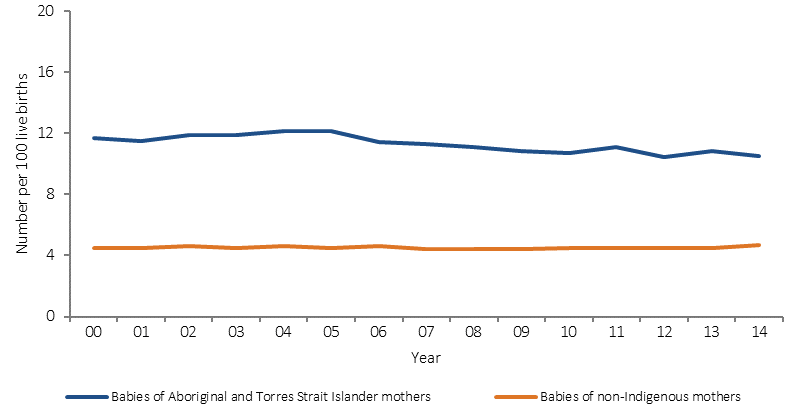

The following analysis is based on the Indigenous status of the mother and live born babies excluding multiple births. NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and the NT had adequate data quality for long-term trends. The low birthweight rate for babies born to Indigenous mothers declined by 13% between 2000 and 2014 (11.7% and 10.5% respectively) in these jurisdictions and there has been a narrowing of the gap.

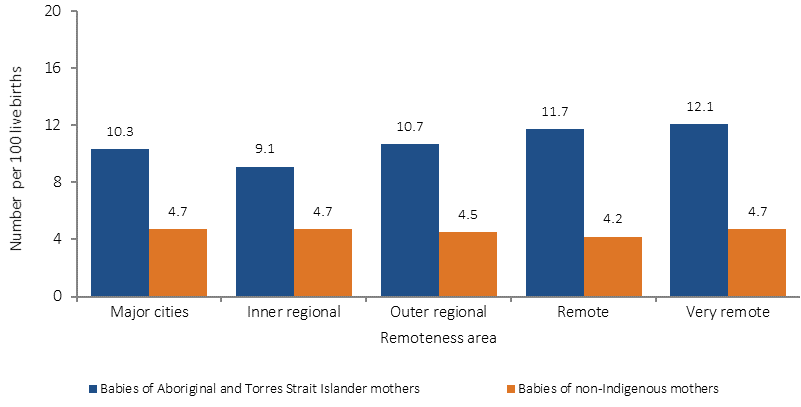

In 2014, nationally, low birthweight rates for babies born to Indigenous mothers were highest in very remote areas (12.1%), followed by remote areas (11.7%), outer regional areas (10.7%), major cities (10.3%) and inner regional areas (9.1%). However, for non-Indigenous mothers the rates were lowest in remote areas (4.2%) followed by outer regional (4.5%) and 4.7% elsewhere.

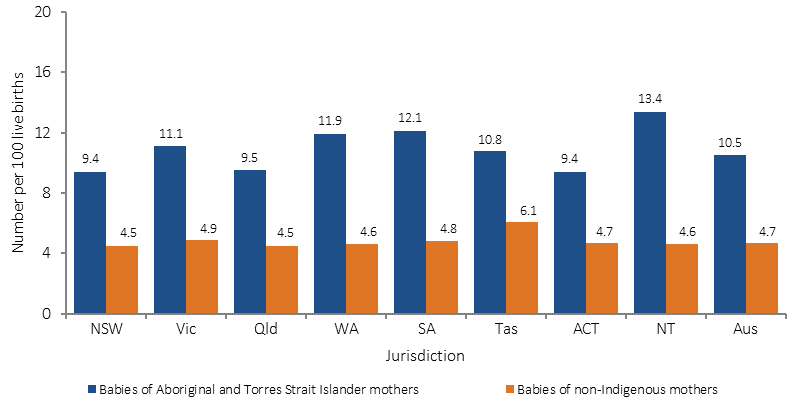

The low birthweight rate for babies born to Indigenous mothers was highest in the NT (13.4%) and lowest in NSW and ACT (both 9.4%).

Most low birthweight babies were born pre-term (68% for babies born to Indigenous mothers and 71% for non-Indigenous mothers). The rate of low birthweight births that were full-term was higher for Indigenous mothers compared with non-Indigenous mothers (32% and 29% respectively).

In 2014, 12% of babies born to Indigenous mothers were born pre-term (compared with 8% of babies of non-Indigenous mothers). Babies of Indigenous mothers who smoked were 1.5 times as likely to be born pre-term as babies born to non-Indigenous mothers who smoked.

The mean birthweight for infants born to Indigenous mothers in 2014 was less than babies of non-Indigenous mothers (3,217 grams compared with 3,356 grams respectively).

A multivariate analysis of perinatal data for the period 2012–14 indicates that, excluding pre-term and multiple births, 51% of low birthweight births to Indigenous mothers were attributable to smoking, compared with 16% for other Australian mothers (see AIHW Detailed Analyses). After adjusting for age differences and other factors, it was estimated that if the smoking rate among Indigenous pregnant women was the same as it was for other Australian mothers, the proportion of low birthweight babies could be reduced by 40%. A study in Qld found that, after excluding pre-term and multiple births, 76% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers who gave birth to a low birthweight baby reported smoking during pregnancy (Khalidi et al, 2012).

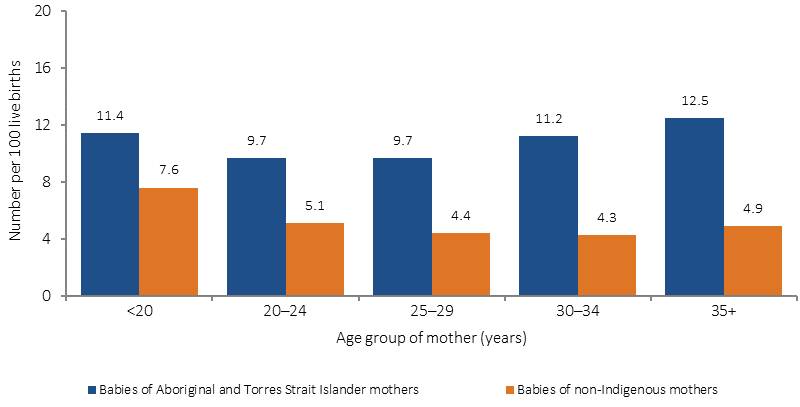

For Indigenous mothers, the percentage of low birthweight births was highest for those in the 35 years and over age group (12.5%), while for non-Indigenous mothers rates were highest for those aged less than 20 years (7.6%).

Compared with Indigenous women who received antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy, those who received no antenatal care were about 4 times as likely to have a pre-term or low-weight baby. The 2014–15 Social Survey showed that women with low birthweight babies were less likely to have had regular check-ups during pregnancy that those who had babies not of low birthweight (84% and 98% respectively).

International rate comparisons should be treated with caution because of differences in methods used to classify and collect data, and the quality and reliability of data in each country. In New Zealand, 2012 data indicates the proportion of babies born with low birthweight was higher for Maori mothers than other mothers (6.8% compared with 5.8%). Similarly, in Canada, 7% of mothers of Inuit inhabited regions had babies of low birthweight compared with 6% of all mothers (2004–08). In 2012, the proportion of low birthweight babies among American Indian and Alaska Native mothers was 7.6% compared with 8.0% for other American mothers. In Canada, high birthweight was the bigger issue among Aboriginal peoples, linked with maternal diabetes (Smylie et al, 2010). Perinatal data show that in 2014, 1.5% of babies born to Indigenous Australian mothers were of high birthweight (4,500 grams and over), as were 1.5% of babies born to non-Indigenous mothers.

Figures

Figure 1.01-1

Low birthweight per 100 live born singleton babies, by Indigenous status of mother, (NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT), 2000 to 2014

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 1.01-2

Low birthweight per 100 live born singleton births, by Indigenous status of the mother and jurisdiction, 2014

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 1.01-3

Low birthweight per 100 live born singleton births, by maternal age and Indigenous status, 2014

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 1.01-4

Low birthweight per 100 live born singleton births, by Indigenous status of the mother and remoteness, 2014

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection

Implications

While there has been a long-term decline in low birthweight trends there needs to be intensified focus on reducing smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy and increasing early and regular access to antenatal care. Maternal nutrition is also an area where more work is needed (Lucas et al, 2014).

Multivariate analysis of perinatal data suggests that large improvements will result from lowering rates of smoking during pregnancy. National data on alcohol consumption would be a useful addition to this collection and analysis.

Perinatal data also indicates that the earlier a woman first accesses antenatal care, the lower the likelihood of having a baby with low birthweight (see measure 3.01). Research confirms that appropriate antenatal care (including improved management of high-risk pregnancies) and a healthy environment for the mother can improve the chances that the baby will have a healthy birthweight (Herceg, 2005; Taylor, LK et al, 2013).

Australian governments are investing in a range of initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. Detailed descriptions are included in the Policies and Strategies section and briefly include the following.

National Evidence-Based Antenatal Care Guidelines have been developed and include information to provide culturally appropriate information for the health needs of Indigenous pregnant women and their families.

The 2014–15 Budget provided funding of $94 million for the Better Start to Life approach to expand New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services, and the Australian Nurse–Family Partnership Program.

The Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme has allocated $12 million for Connected Beginnings, a programme which implements an approach to integrated childcare recommended in Creating Parity—the Forrest Review. The Department of Education has also allocated $30 million over three years to support the programme.

In SA, the Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (a partnership model between Aboriginal Maternal Infant Care Workers and midwives) supports Aboriginal women and their families through pregnancy, childbirth and up to 6 weeks postnatally. For women in the programme, there has been a decrease in low birthweight rates, infant mortality and the proportion of Aboriginal mothers smoking during pregnancy.

See also measures 3.01 (antenatal care) and 2.21 (health behaviours during pregnancy), particularly smoking.