2.14 Indigenous people with access to their traditional lands

Page content

Why is it important?

Connection to family and community, land and sea, culture and identity has been identified as integral to health from an Aboriginal perspective (NAHSWP, 1989). As stated by Anderson (1996): ‘Our identity as human beings remains tied to our land, to our cultural practices, our systems of authority and social control, our intellectual traditions, our concepts of spirituality, and to our systems of resources ownership and exchange. Destroy this relationship and you damage—sometimes irrevocably—individual human beings and their health’. Ongoing access to traditional lands also offers socio-political, economic and environmental benefits (Weir, 2012). Analysis of 2008 Social Survey data found a clear association between cultural attachment and positive socio-economic outcomes and wellbeing (Dockery, 2011).

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, disconnection from Country is considered a form of homelessness. Similarly, many people are less likely to perceive themselves as homeless, regardless of the adequacy of their dwelling, if they are on Country (ABS, 2014a).

Access to traditional lands is not only a determinant of health in remote contexts where Indigenous Australians are more likely to have ownership and control over their Country; it is also a determinant of health for those living in non-remote and urban areas. Research in Victoria has found the role of Country in strengthening self-esteem, self-worth, pride, cultural and spiritual connection and positive states of wellbeing (Kingsley et al, 2013).

Caring for Country means participation in activities on traditional land, with the objective of promoting ecological, spiritual and human health (Berry, HL et al, 2010). In central Arnhem Land, a cross-sectional study of almost 300 Indigenous adults aged 15–54 years found that participation in Caring for Country was associated with better health outcomes including diet, physical activity, mental health and lowered risk of diabetes, kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, after controlling for socio-economic characteristics and health behaviours (Burgess, CP et al, 2009).

Findings

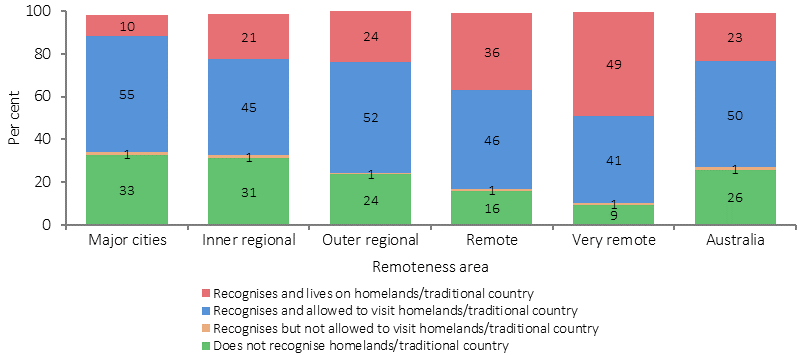

In 2014–15, 74% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults reported that they recognised their homeland or traditional country. Nearly one-quarter (23%) reported they lived on their homelands, 49% did not live on homelands but were allowed to visit, and 1% were not allowed to visit their homelands/traditional country.

Indigenous Australians in the 45–54 year age group were more likely to recognise their homelands than those in the 15–24 year age group (85% compared with 63%). Note that 11% of Indigenous Australians reported they had been removed from their family, and 36% reported that they had relatives removed from their family.

Those who lived in remote areas (89%) were more likely than those in non-remote areas (70%) to recognise homelands/traditional country, and more likely to live on homelands/traditional country (44% compared with 17% respectively). More Indigenous Australians in remote areas identified with a clan, tribal or language group (79%) compared with those in non-remote areas (58%).

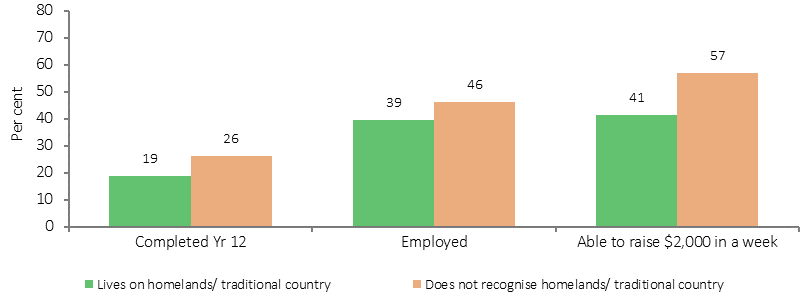

The 2014–15 Social Survey provides opportunities to analyse relationships between access to lands and other factors. The analysis outlined below summarises simple associations found in the data; further multivariate analysis is needed to explore the complex interactions between these issues. Compared with those who do not recognise homelands, those who lived on homelands/traditional country were less likely to have completed Year 12 (19% compared with 26%), to be employed (39% compared with 46%), or be living in households that were able to raise $2,000 in a week (41% compared with 57%). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who lived on homelands were also more likely than those who do not recognise homelands to report problems accessing health services (17% compared with 12%).

In 2014–15, over 50% of Indigenous rangers and Indigenous Protected Areas projects reported an improvement in the health and overall wellbeing of their rangers (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2016).

Figures

Figure 2.14-1

Access to homelands/traditional country, by remoteness area, Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 2.14-2

Selected socio-economic characteristics by whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people recognised/did not recognise homelands/traditional country, 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS

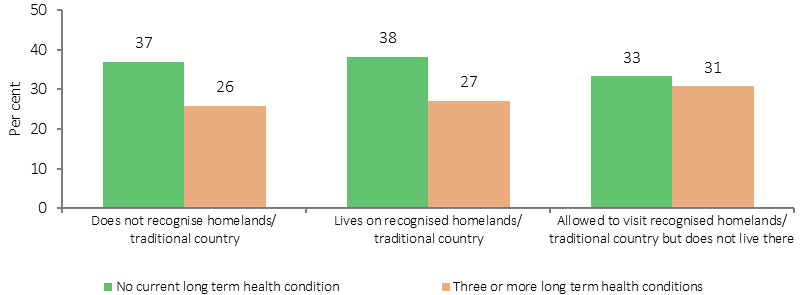

Figure 2.14-3

Long term health conditions by whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people recognised/did not recognise homelands/traditional country, 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS

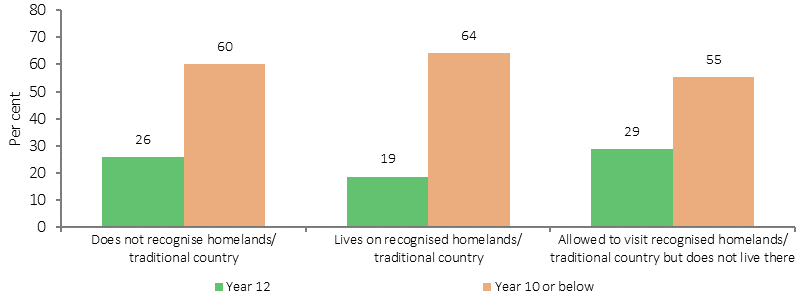

Figure 2.14-4

Highest year of school completed by whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people recognised/did not recognise homelands/traditional country, 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS

Implications

While the evidence suggests there are health benefits in connections to Country and culture, for many people, living on Country is not an option. For those living in non-remote areas, visits may be the only realistic possibility.

Indigenous Australians’ rights and interests in land are formally recognised in around 40% of the land area of Australia. A further 37% of Australia is subject to application for recognition of native title rights.

The Government recognises the importance, to Indigenous Australians, of maintaining connection to land and waters. This connection is the basis of relationships, identities, cultural practices and Indigenous wellbeing at both the individual and community level.

The Australian Government is aiming to resolve all current native title claims within a decade as part of its comprehensive plan set out in the Developing Northern Australia White Paper. The Government will continue to provide $110 million per year over the next four years to support this aspiration.

In addition, the Commonwealth has committed $1 million in additional funding over the next four years for the Aboriginal Land Commissioner to support the resolution of remaining land claims in the Northern Territory.

As part of the Developing Northern Australia White Paper, the Government, in partnership with various state and territory governments and Indigenous organisations, is implementing a number of measures which support Indigenous peoples’ access and use of land. These measures support innovative changes that simplify land use arrangements and attract more investment across northern Australia. The Government has allocated $10.6 million for pilot projects that broaden economic activity and demonstrate the benefits of land reform. The Government also is investing $17 million for township lease negotiations and land administration measures aimed at increasing economic activity on Indigenous land in the Northern Territory, as well as $20.4 million (over four years, ongoing) to build the capacity of native title corporations across Australia.

In December 2015, COAG considered the report of the investigation into Indigenous land administration and use (‘the Investigation’). The Investigation makes recommendations to support Indigenous people to use their rights in land and waters for economic development. These include recommendations that go to supporting native title determination processes, removing legislative barriers to bankable long-term leases, and supporting the capacity and autonomy of Indigenous land owners.

COAG agreed jurisdictions would implement the recommendations of the Investigation’s report, subject to their circumstances and resource constraints. The Commonwealth Minister for Indigenous Affairs is due to report back on implementation of the recommendations after 12 months in late 2016.

South Australia has a Mobile Dialysis Unit which is a specially designed truck that has been fitted with three dialysis chairs and visits remote Aboriginal communities across SA. The Unit allows Aboriginal dialysis patients living in regional or metropolitan centres to visit their home communities. The Unit commenced operating in 2014 and has visited many communities allowing people to return home for significant community events and to spend time on Country with family and friends.