2.22 Overweight and obesity

Page content

Why is it important?

Overweight and obesity is a global health problem (OECD, 2014)(OECD 2014). Being overweight or obese increases the risk of a range of health conditions, including coronary heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, some cancers, respiratory and joint problems, sleep disorders and social problems. The excess burden of obesity in the Indigenous population is estimated to explain 1 to 3 years (9% to 17%) of the life expectancy gap in the NT (Zhao et al, 2013a). High body mass was the second leading risk factor contributing to the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in 2011, accounting for 14% of the gap (AIHW, 2016f). High body mass contributed to 64% of the burden of diabetes for Indigenous Australians, 46% of the chronic kidney disease burden and 39% of the coronary heart disease burden.

Findings

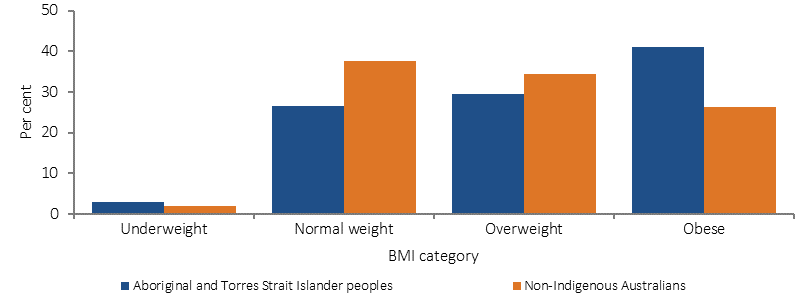

There is no new data for overweight/obesity available from the 2014–15 Social Survey. In 2012–13 the Health Survey included height and weight measurements to allow body mass index (BMI) scores to be calculated. In 2012–13, 66% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over had a BMI score in the overweight or obese range (29% overweight and 37% obese). Indigenous adults were 1.6 times as likely to be obese as non-Indigenous Australians (after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations).

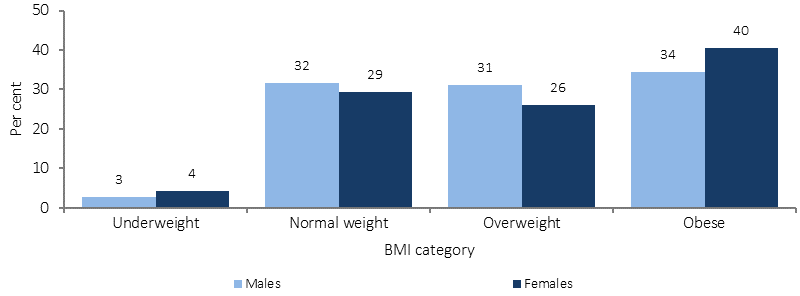

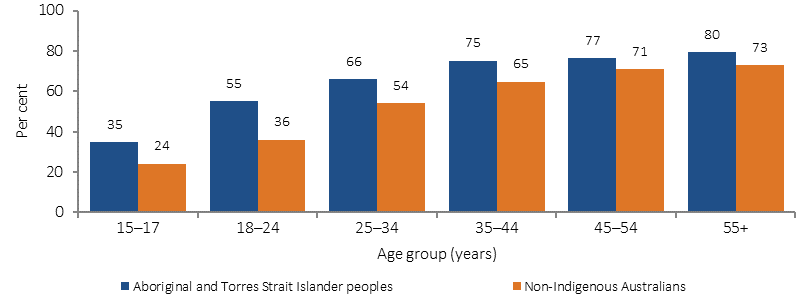

Indigenous obesity rates varied geographically. Obesity was highest in inner regional areas (40%) and lowest in very remote areas (32%). Rates were similar in major cities (37%) and in outer regional and remote areas (38%). By jurisdiction, obesity rates ranged from 41% in NSW to 29% in the NT. Indigenous women had higher rates of obesity (40%) and lower rates of overweight (26%) compared with Indigenous men (34% and 31% respectively). Of those adult Indigenous women who had an underweight or normal measured BMI, 44% had a waist circumference of 80cm or more, indicating increased risk of developing chronic disease. For both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and females, the rates for overweight/obesity increased with age, with 80% of the population aged 55 years and over being overweight or obese. Higher proportions of Torres Strait Islanders were overweight/obese than in the Aboriginal population (73% versus 65%).

The 2012–13 Health Survey showed obesity was strongly associated with chronic disease biomarkers (being obese increased the risk of abnormal test results for nearly every chronic disease tested for in the survey). Indigenous obese adults were 7 times more likely to have diabetes than those of normal weight/ underweight (17% compared with 2%). Those who did not meet the physical activity guidelines were more likely to be obese (44%) than those who met the guidelines (36%).

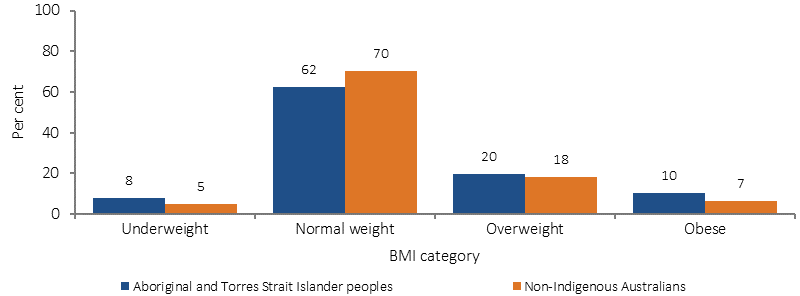

Childhood is a critical period in which inequalities in health determinants such as socio-economic status and overweight/obesity emerge (Jansen et al, 2013; Thurber et al, 2014; Kim et al, 2017). In 2012–13, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 2–14 years were more likely than non-Indigenous children to be underweight (8% compared with 5%); were less likely to be in the normal weight range (62% compared with 70%); and more likely to be overweight or obese (30% compared with 25%). Obesity rates for Indigenous children increased from the age of 5, with the highest rates at 10–14 years of age (12%). High BMI is found to be a predictor of short sleep duration and sleep apnoea for children (Magee et al, 2014; Kassim et al, 2016), which impacts on school performance (measure 2.04) and engagement in physical activity (measure 2.18). It is not possible to compare 2012–13 Health Survey results with previous surveys as the latest results are based on measured BMI rather than self-reported height and weight (as was done before). Research shows rates of overweight/ obesity have increased more rapidly in Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal school-aged children in NSW (Hardy et al, 2014).

In May 2015, national Key Performance Indicators data from 214 Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations, found that 27% of regular clients aged 25 years and over were overweight, and 43% were obese.

Obesity is associated with other health risk factors and social determinants of health. One example is prolonged financial stress, which is a predictor of obesity (Siahpush et al, 2014) (see measure 2.08). Low income is associated with food security problems (Markwick et al, 2014) and subsequent dietary behaviour (see measure 2.19). Evidence also shows that incarceration is associated with weight gain and obesity in Indigenous youth (Haysom et al, 2013) (see measure 2.11).

Figures

Figure 2.22-1

Proportion of persons aged 15 years and over (age-standardised) by BMI category and Indigenous status, 2012–13

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS

Figure 2.22-2

Proportion of Indigenous persons aged 15 years and over by BMI category, by sex, 2012–13

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS

Figure 2.22-3

Proportion of children aged 2–14 years by BMI category and Indigenous status, 2012–13

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS

Figure 2.22-4

Proportion of persons aged 15 years and over who were overweight or obese, by Indigenous status and age, 2012–13

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS

Implications

Given the health risks associated with being obese or overweight, the situation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples requires urgent attention. It is second only to tobacco use in terms of contribution of modifiable risk factors to the health gap experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (AIHW, 2016f).

An evaluation of a school-based health education programme for urban Indigenous youth found promising results in physical activity, breakfast intake and fruit and vegetable consumption (Malseed et al, 2014), all of which are core components of healthy weight management. Likewise, opportunities exist for obesity prevention in young children through practice-nurse brief interventions (Denney-Wilson et al, 2014).

Reversal of obesity is difficult even in the absence of environmental and social barriers. Therefore, early intervention to prevent the onset of excessive weight gain is likely to be the most effective strategy (Thurber et al, 2014). Studies reporting success in reducing obesity have a number of common characteristics, including: a focus on physical activity and diet opposed to diet alone; the ability to accommodate the preferences of participants; a group focus; and choice between a number of physical activities. Programmes must also be culturally acceptable, conveniently located, easily incorporated into the daily schedule and show goal attainment that is realistic and appropriate (Canuto et al, 2011).

The Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023 identifies the importance of addressing the social and cultural determinants of health to accelerate reducing the inequalities that lead to poorer health outcomes, including unhealthy weight and obesity.

In addition, in 2016 the Australian Government released the Healthy Weight Guide which provides information about healthy weight, physical activity and healthy eating; tips and tools to assist with achieving and maintaining a healthy weight; and a registered area where users can record and track their weight and progress. The Healthy Weight Guide has an area dedicated to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In 2014 the Australian Government launched the Healthy Bodies Need Healthy Drinks resource package. This suite of promotional materials encourages school-aged children, their families and communities to choose water instead of high-sugar drinks in an effort to prevent obesity, chronic disease and dental caries. There is international evidence that the consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks leads to weight gain. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children consume higher quantities of soft drink per person compared with non-Indigenous children (Thurber et al, 2014). The odds of consuming sugar-sweetened drinks are significantly higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children whose mothers have lower levels of education, who experience housing instability, who are living in urban areas and who are living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

Move Well Eat Well (primary schools and early childhood settings) in Tasmania aims to improve the policies and practices in these settings to support nutrition and physical activity.