1.04 Respiratory disease

Page content

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience higher mortality and morbidity from respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (including bronchitis and emphysema), pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease than other Australians.

High rates of pneumonia are associated with factors such as respiratory diseases, poor living conditions, malnutrition, smoking and alcohol misuse (Lim et al, 2014; Grau et al, 2014; Janu et al, 2014). Young children and those in older age groups are most at risk. Indigenous children in the NT have rates of radiologically confirmed pneumonia that are among the highest in the world (O'Grady, 2010).

Asthma can impact on physical functioning and attendance at school and work. It commonly coexists with other chronic conditions and low socio-economic status. Deaths due to asthma occur in all age groups, but the risk of dying from asthma increases with age.

COPD is a serious lung disease that mainly affects older people and is associated with and caused by smoking, environmental pollutants and/or childhood infectious diseases (AIHW, 2014c). Currently, 42% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over smoke, 2.7 times the non-Indigenous rate (see measure 2.15). COPD is characterised by chronic obstruction of lung airflow that interferes with breathing. Previous studies have found that among Indigenous Australians aged 55 years and over hospitalised for COPD, cancer is a commonly associated condition (AIHW, 2011b; 2014c).

Findings

Respiratory diseases (excluding acute infections) were responsible for 8% of the total disease burden among Indigenous Australians in 2011 (AIHW, 2016f). Asthma and COPD caused 41% and 38% of this burden respectively. The burden from respiratory diseases in Indigenous Australians occurred at a rate 2.5 times that of non-Indigenous Australians.

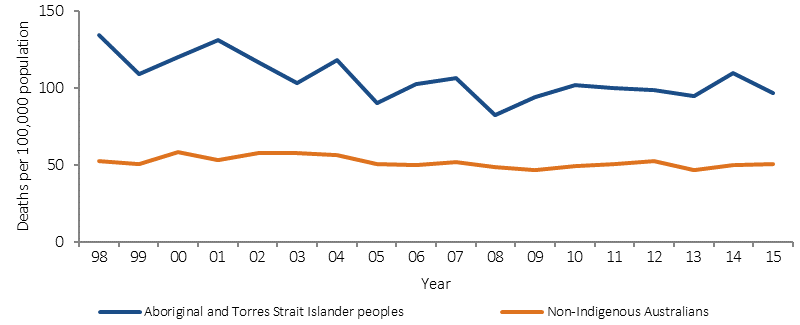

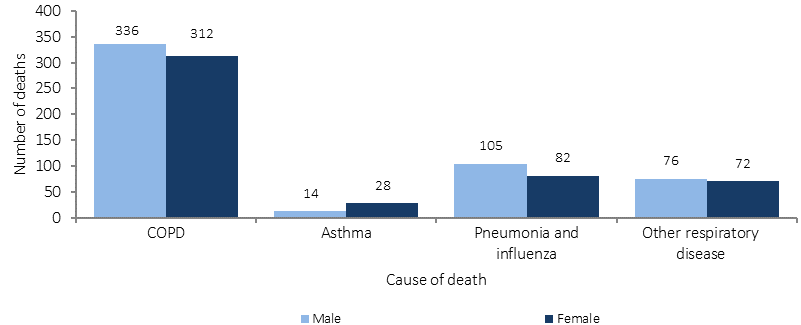

In 2011–15 there were 1,092 respiratory disease deaths among Indigenous Australians in NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined (8% of Indigenous deaths). This was twice the non-Indigenous rate. For respiratory deaths among Indigenous Australians, 59% were attributed to COPD, 17% to pneumonia and influenza and 4% to asthma. There has been a significant decline in respiratory disease mortality rates among Indigenous Australians since 1998.

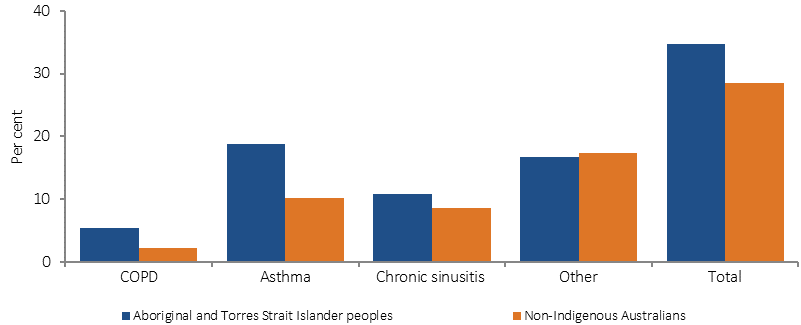

Self-reported data on respiratory diseases is available from the 2012–13 Health Survey. In 2012–13, 31% of Indigenous Australians reported long-term respiratory diseases that had lasted 6 months or more. The most commonly reported respiratory condition was asthma (18%) followed by chronic sinusitis (8%) and COPD (4%). Asthma has increased since 2004–05 from 15% of the Indigenous population to 18% in 2012-13.

Indigenous females reported higher rates of respiratory diseases (34%) than males (28%). Indigenous Australians living in non-remote areas reported higher rates (35%) than those in remote areas (18%). Rates varied by jurisdiction from 13% in the NT to 44% in the ACT. There was also an increase with age, ranging from 21% for 0–14 year olds to 43% in the 45–54 year group.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 2.5 times as likely to report COPD and 1.9 times as likely to report asthma as non-Indigenous Australians in 2012–13.

Although hospitalisation statistics reflect separations from hospital rather than the prevalence or incidence of diseases in the community, they are a measure of the occurrence of conditions requiring acute care. Between July 2013 and June 2015, there were 43,662 hospitalisations for respiratory disease among Indigenous Australians (9.5% of Indigenous hospitalisations excluding dialysis).

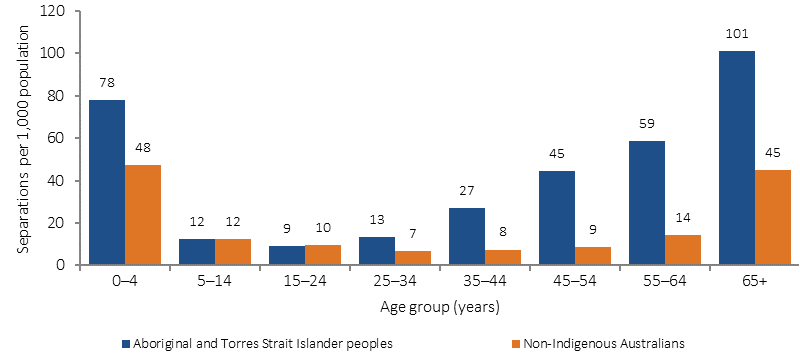

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, the Indigenous hospitalisation rate for respiratory disease was 2.4 times the non-Indigenous rate. The Indigenous hospitalisation rate was highest in the 65 years and over age group (101 per 1,000) and second highest in the 0–4 years group (78 per 1,000).

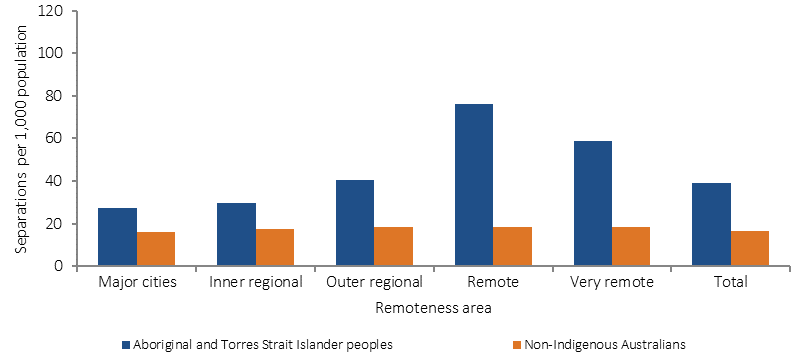

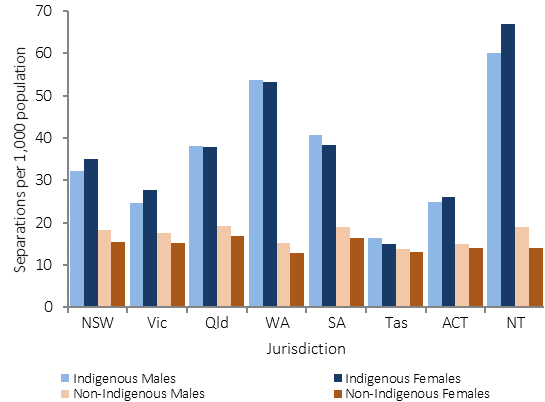

Hospitalisation rates for respiratory diseases were highest in the NT (64 per 1,000) and WA (53 per 1,000). Rates in remote areas were 2.8 times the rates in major cities for Indigenous Australians but rates were similar across areas for non-Indigenous Australians. Since 2004–05, there has been an 18% increase in respiratory disease hospitalisation rates in the six jurisdictions with adequate data for trend reporting (NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined). Rates for Indigenous children aged 0–4 years increased by 24% over the same period.

In the period July 2013 to June 2015, COPD (29%) was the most common type of respiratory disease for which Indigenous Australians were hospitalised. This was followed by pneumonia (21%). The greatest differences between the two populations were for COPD and pneumonia (3.6 and 3.1 times respectively). In the period 2013–15 there were 594 notifications of invasive pneumococcal disease for Indigenous Australians, representing 13% of all cases notified.

Figures

Figure 1.04-1

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for respiratory disease by Indigenous status and remoteness, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.04-2

Age-specific hospitalisation rates for respiratory disease, by Indigenous status, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.04-3

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for respiratory disease, by Indigenous status, sex, and jurisdiction, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.04-4

Proportion reporting respiratory disease (age-standardised), by Indigenous status, 2012–13

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012-13 AATSIHS

Figure 1.04-5

Age-standardised mortality rates for respiratory diseases, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA & NT, 1998 to 2015

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

Figure 1.04-6

Deaths of Indigenous Australians by type of respiratory disease, by sex, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT, 2011–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

Implications

While Indigenous respiratory disease mortality rates have fallen since 1998; self-reported respiratory disease, hospitalisation and mortality rates are still twice as high for Indigenous people. Initiatives addressing smoking (including second-hand smoke), immunisation, living conditions, overcrowding, chronic disease and access to health care are likely to contribute to improvements in respiratory disease (Torzillo & Chang, 2014; Johnston et al, 2010).

A range of studies of respiratory disease services have been undertaken including a study in WA that found implementation of an integrated COPD multidisciplinary community service reduced respiratory hospitalisations in the long-term (Chung et al, 2016). A large pilot study in QLD showed the importance of working with communities and Indigenous staff in the development and delivery of a culturally appropriate and accessible specialist respiratory service (Medlin et al, 2014).

The Indigenous Australians' Health Program (IAHP) focuses on the prevention, early detection and management of chronic disease through expanded access to and coordination of comprehensive primary health care. Activities aimed at helping patients who experience respiratory disease include Tackling Indigenous Smoking and a care coordination and outreach workforce based in AMSs and mainstream services. In addition, GP health assessments for Indigenous Australians are funded under the MBS, which includes follow-on care. Funding is also provided for incentive payments for improved chronic disease management, and for cheaper medicines through the PBS. A new National Asthma Strategy is being developed which includes Indigenous Australians as a priority group.