3.01 Antenatal care

Page content

Why is it important?

Antenatal care involves recording medical history; undertaking regular clinical assessments to identify individual needs; screening for a range of infections and abnormalities; providing support and information; offering social, lifestyle and self-care advice; and providing first-line management and referral if necessary (AHMAC, 2012; WHO, 2007). Regular antenatal care that commences early in pregnancy has been found to have a positive effect on good health outcomes for mothers and babies (Eades, S, 2004; AHMAC, 2012; Arabena et al, 2015). Well-managed discharge processes and programmes that continue after birth have also shown benefits for child health, development and family wellbeing (Sivak et al, 2008).

Antenatal care may be especially important for Indigenous women as they are at higher risk of giving birth to pre-term and low birthweight babies and have greater exposure to other risk factors and complications such as anaemia, poor nutritional status, chronic illness, hypertension, diabetes, genital and urinary tract infections, smoking, and high levels of psychosocial stressors (de Costa & Wenitong, 2009; AHMAC, 2012).

The Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care—Module 1 (AHMAC, 2012) and Module 2 (AHMAC, 2014) provide recommendations to support high-quality antenatal care and contribute to improved outcomes for all mothers and babies. The guidelines take a woman-centred approach and include specific discussion of antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to improve their experience and outcomes of care.

Presentation for antenatal care within the first 10 weeks of gestation is suggested due to the high information needs early in pregnancy and to allow for timely assessment of risk factors. Depending on need, a schedule of 10 visits is recommended for a woman’s first pregnancy, and 7 visits for subsequent uncomplicated pregnancies.

Many factors influence an Indigenous woman’s engagement with, and early presentation for, antenatal care including availability of culturally appropriate services, the frequency (or absence) of local clinics, transport, and educational, socio-economic and financial issues (Arnold, JL et al, 2009; de Costa & Wenitong, 2009).

Findings

Perinatal data show that in 2014, 99% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers accessed antenatal care services at least once during their pregnancy, which is similar to non-Indigenous mothers. However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, on average, accessed services later in the pregnancy and had fewer antenatal care sessions than non-Indigenous mothers.

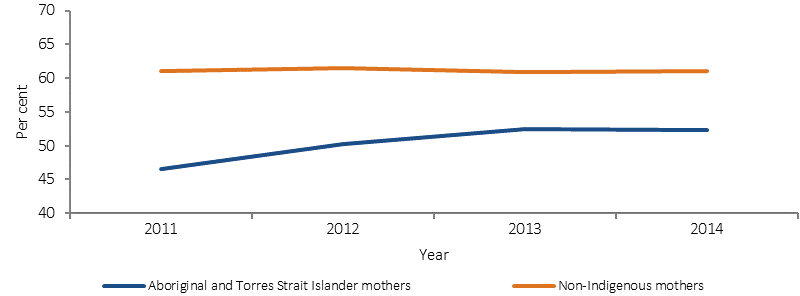

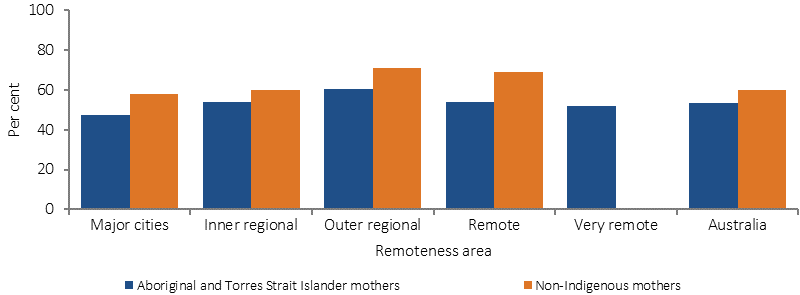

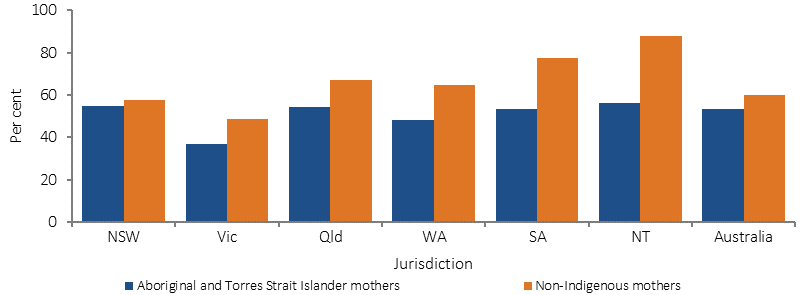

The majority of Indigenous mothers (54% in 2014) attended antenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy and 86% attended five or more times during their pregnancy. From 2011 to 2014, the proportion of Indigenous mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy increased by 13%. However, in 2014 the age-standardised proportion of Indigenous mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester was still lower than for non-Indigenous mothers (by 7 percentage points, 53% compared with 60% respectively). For Indigenous mothers the rate was highest in outer regional areas (60%) and lowest in major cities (47%) (AIHW, 2016y).

The Indigenous rate was lowest in Vic (37%); while both the NT and SA had the largest gaps (31 and 24 percentage points respectively).

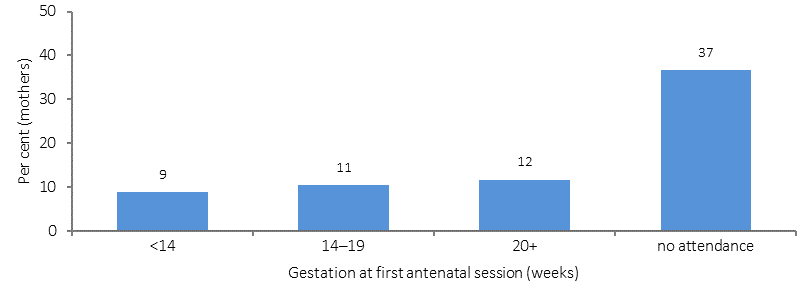

Compared with women who received care in the first trimester, women who received no antenatal care were about 4 times as likely to have a pre-term or low birthweight baby.

In 2014, for women who gave birth at 32 weeks gestation or more, 86% of Indigenous mothers had attended 5 or more antenatal sessions compared with 95% for non-Indigenous mothers.

In the 2014–15 Social Survey, the vast majority (94%) of mothers of Indigenous children aged 0–3 years reported that they had regular pregnancy check-ups.

The national Key Performance Indicators data collection includes items on antenatal care provided by Indigenous primary health care organisations. In May 2015, of the 5,160 Indigenous mothers who were regular clients of these organisations, 37% attended their first antenatal visit in the critical first trimester (note these data report <13 weeks rather than <14 weeks). Attendance rates were highest in remote and inner regional areas (41% and 40% respectively) and lowest in major cities (30%).

Figures

Figure 3.01-1

Age-standardised percentage of mothers who attended at least one antenatal care session during the first trimester, by Indigenous status, Vic, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2011 to 2014

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 3.01-2

Age-standardised percentage of mothers whose first antenatal care session occurred in the first trimester, by Indigenous status and remoteness, 2014

Source: AIHW (unpublished) National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 3.01-3

Age-standardised percentage of mothers whose first antenatal care session occurred in the first trimester, by Indigenous status and jurisdiction, 2014

Note: Australia includes ACT and Tas

Source: AIHW/NPESU analysis of National Perinatal Data Collection

Figure 3.01-4

Relationship for Indigenous mothers between duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care session and low birthweight babies, 2014

Source: AIHW/NPESU analysis of National Perinatal Data Collection

Implications

Continued improvements in the quality of antenatal care received, earlier and more regular attendance for antenatal care, along with programs after birth are required to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and their babies. The features that have been identified for quality primary maternity services in Australia include high quality care that is enabled by evidence-based practice, coordinated according to the woman’s clinical needs and preferences, based on collaborative multidisciplinary approaches, woman-centred, culturally appropriate and accessible at the local level (AHMAC, 2012).

Reviews of the literature have identified the following key success factors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal health programmes to complement the features detailed above: a safe/welcoming environment; outreach and home visiting; flexibility in service delivery and appointment times; access to transport; continuity of care and carer integration with other services (e.g. AMS or hospital); a focus on communication, relationship building and trust; involvement of women in decision making; respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture; respect for privacy, dignity and confidentiality; family involvement and childcare; appropriately trained workforce; Indigenous staff and female staff; informed consent and right of refusal; and tools to measure cultural competency (Dudgeon et al, 2010; Reibel & Walker, 2010; Herceg, 2005; AHMAC, 2012; Bertilone & McEvoy, 2015; Kildea & Van Wagner, 2013; Kildea et al, 2012; Murphy & Best, 2012; Wilson, G, 2009).

Australian governments are investing in a range of initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. These are described in detail in the Policies and Strategies section and briefly below.

The Better Start to Life approach, was allocated Australian Government funding New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services and the Australian Nurse Family Partnership Program, which was also allocated $1.1 million under the Women’s Safety Package to help support families experiencing domestic violence.

The Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme has allocated $12 million for Connected Beginnings, a programme which implements an approach to integrated childcare recommended in Creating Parity—the Forrest Review. The Department of Education has also allocated $30 million over three years to support the program.

In the 2014–15 Budget, the National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) Action Plan was allocated $9.2 million.

National Evidence-Based Antenatal Care Guidelines have been developed to help ensure women are provided consistent, quality, evidence-based maternity care. Advice specific to meeting the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pregnant women is included.

The Pregnancy, Birth and Baby helpline and website, provides a range of support to women, partners and families in relation to pregnancy and parenting.

Community based pregnancy support and hospital antenatal services for young Aboriginal women and their families have continued in Tasmania. In particular, the state-wide Aboriginal Midwifery Outreach Project, with midwives based in Aboriginal health services, provides holistic antenatal and postnatal care and support, including home visits to Aboriginal women and women having Aboriginal babies.

The Koori Maternity Services programs, operating at 14 sites across Victoria, continue to increase the participation of Aboriginal women in antenatal and postnatal care services.

Strategies operating in WA include Collaborative Child Health, a birth to school entry project in the Pilbara region. Wirraka Maya allocated funding to primary prevention in Aboriginal communities, which included an alcohol in pregnancy intervention, and also implemented the ‘0–5 High Risk Program’ across the Pilbara for children aged 0–5 years living within high risk environments.

In SA, the Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (a partnership model between Aboriginal Maternal Infant Care Workers and midwives) supports Indigenous women and their families through pregnancy, childbirth and up to 6 weeks postnatally, improving outcomes for mothers and babies in the programme.