1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisation

Page content

Why is it important?

Hospitalisation rates indicate two main issues: the occurrence in a population of serious acute illnesses and conditions requiring admitted patient hospital treatment; and the access to and use of hospital admitted patient treatment by people with such conditions. Hospitalisation rates for a particular disease do not directly indicate the level of occurrence of that disease in the population. For diseases that usually do not cause an illness that is serious enough to require admission to hospital, a high level of occurrence will not be reflected in a high level of hospitalisations.

Hospitalisation rates are based on the number of hospital episodes rather than on the number of individual people who are hospitalised. A person who has frequent hospitalisations for the same disease is counted multiple times in the hospitalisation rate for that disease. For example, each kidney dialysis treatment is counted as a separate hospital episode, so that each person receiving 3 dialysis treatments per week contributes approximately 150 hospital episodes per year. Therefore, it is especially important to separate hospitalisation rates for dialysis from rates for other conditions. Each hospitalisation involves a principal diagnosis (i.e. the problem that was chiefly responsible for the patient's episode of care) and additional diagnoses where applicable (i.e. conditions or complaints either coexisting or arising during care). This report focuses on the principal diagnosis for each hospitalisation. Analysis of additional diagnoses is available from the AIHW website. Rates of hospitalisation are also impacted by the availability of primary care services (see measure 3.07) and other alternative services.

Findings

During the two years to June 2015, there were an estimated 458,000 hospital separations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (excluding dialysis). After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, Indigenous Australians were hospitalised at 1.3 times the non-Indigenous rate.

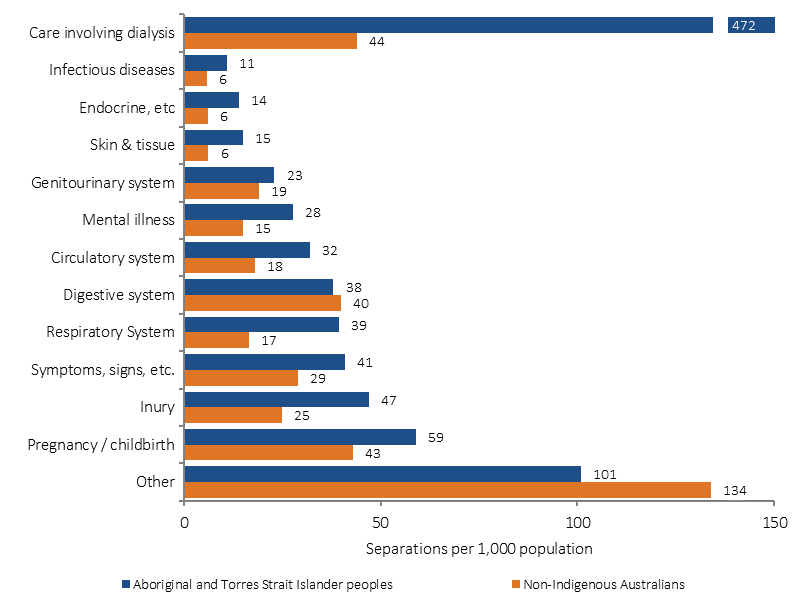

Hospital episodes of care involving dialysis accounted for 46% of all hospitalisations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (compared with 12% for non-Indigenous Australians). The hospitalisation rate for dialysis among Indigenous Australians was 11 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (see measure 1.10). Among Indigenous Australians, injury and poisoning was the second leading cause of hospitalisation (7%), followed by pregnancy and childbirth (6%), diseases of the respiratory system (5%) and diseases of the digestive system (5%).

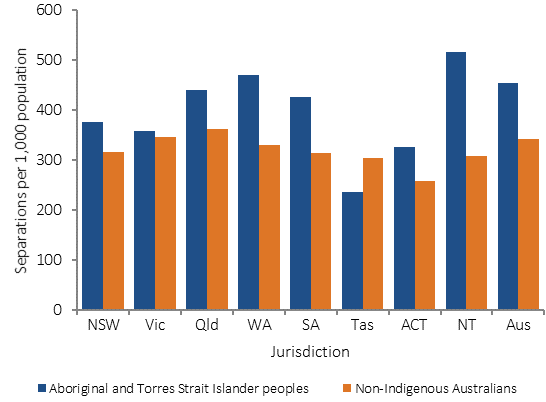

Among Indigenous Australians, the highest hospitalisation rate was in the NT (517 per 1,000 population) followed by WA (470 per 1,000 population). The difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous hospitalisation rates was highest in the NT (209 per 1,000 population) followed by WA (139 per 1,000 population). Hospitalisation rates for Indigenous Australians were highest in remote areas (597 per 1,000), lower in very remote areas (496 per 1,000) and lowest in major cities (356 per 1,000). For non-Indigenous Australians, rates were similar across geographic areas (around 316–344 per 1,000) except in very remote areas where rates were lower (291 per 1,000). The largest gaps between rates for the two populations were in remote and very remote areas.

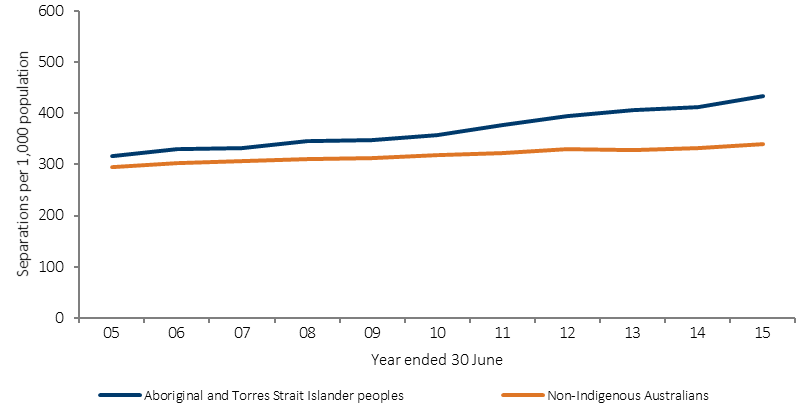

Hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples increased significantly over the period 2004–05 to 2014–15 (NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined). Over this period, rates increased faster for Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians, resulting in an increase in the difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous hospitalisation rates. As a proportion of the increase in the numbers of Indigenous hospitalisations between the period 2004–05 to 2005–06 and the period 2013–14 to 2014–15, 53% was for dialysis. However, after excluding dialysis, 12% of the increase was for injury, followed by 12% for signs, symptoms and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings.

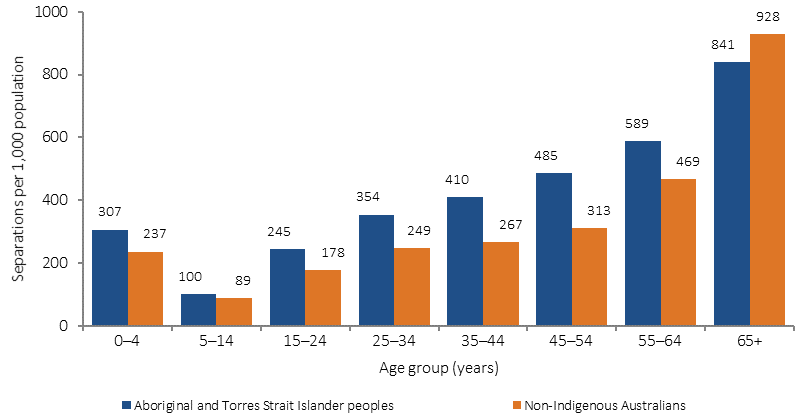

Hospitalisations were higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than for non-Indigenous Australians across all age groups below 65 years. The difference was greatest in the 45–54 year age group (difference of 173 separations per 1,000 population) and smallest among children aged 5–14 years (difference of 11 separations per 1,000 population). Hospitalisation rates for Indigenous Australians were highest in the 65 years and over age group. However, Indigenous rates were lower than non-Indigenous rates in this age group.

Figures

Figure 1.02-1

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates (excluding dialysis) by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA, and the NT, 2004–05 to 2014–15

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.02-2

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates (excluding dialysis) by state/territory and Indigenous status, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.02-3

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates by principal diagnosis and Indigenous status, Australia, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.02-4

Age-specific hospitalisation rates (excluding dialysis) by Indigenous status, Australia, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Implications

In the two-year period to June 2015, there were approximately 393,200 hospital episodes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for dialysis treatment. Dialysis episodes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples reflect the very high number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with kidney failure, and the relatively low number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients who receive kidney transplants (see measure 1.10). Excluding dialysis, the greatest differences between hospitalisation rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are for episodes of care due to injury and for respiratory conditions. The 30% higher overall hospitalisation rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is less than expected given the much greater occurrence of disease and injury and much higher mortality rates in this population (see measure 1.22). Until the incidence of many health problems is reduced, hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will not decrease. Reductions in hospitalisations will eventually occur through concerted action to reduce the incidence and prevalence of the underlying conditions, and in preventing or delaying complications, through primary health care.

State and Territory governments contribute funding for and are responsible for provision of public hospital services in Australia, including services to Indigenous Australians.

The Australian Government Indigenous Australians' Health Program (IAHP) focuses on the prevention, early detection, and management of chronic disease to help keep people out of hospital, through expanded access to and coordination of comprehensive primary health care. Other programs funded by the Australian Government that aim to reduce avoidable hospitalisations include GP health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people under the MBS, which includes follow-on care. Funding is also provided for incentive payments for improved chronic disease management, and for cheaper medicines through the PBS. Hospitalisation rates will be influenced by reforms to the health system, increased rates of self-identification by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and measures that address the social determinants of health.