1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing

Page content

Why is it important?

Social and emotional wellbeing is a holistic concept based on connections to country, culture, community, family, spirit and physical and mental health. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, health is not just the physical wellbeing of the individual but the ‘social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community’ (SHRG, 2004; Gee et al, 2014; Parker, R & Milroy, 2014; Dudgeon et al, 2014a). Social and economic disadvantage is interconnected with historical loss of land (which was the economic and spiritual base for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities); damage to traditional social and political structures and languages; child removals; incarceration rates and inter-generational trauma (NPHP, 2006; Dudgeon et al, 2014b; Zubrick et al, 2014). Experience of discrimination also leads to psychological distress and has a negative impact on health (Paradies & Cunningham, 2008). Indigenous Australians experience higher levels of morbidity and mortality from mental illness, psychological distress, self-harm and suicide than other Australians.

Findings

The 2014–15 Social Survey collected information on a range of topics relevant to social and emotional wellbeing (ABS, 2016e). This survey showed that Indigenous Australians retain strong links to their culture and family connections. In 2014–15, 62% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported they identified with a clan or language group, 74% recognised an area as homelands/traditional country and 63% were involved in cultural events, ceremonies or organisations in the last 12 months. In 2014–15, 92% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported that they could get support in time of crisis and 97% reported that they had been involved in sporting, social or community activities in the last 12 months.

However, in 2014–15, 47% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported that they and/or a relative had been removed from their natural family. Note: this is of those who were able to state whether family members had been removed. Those who were removed or whose relatives were removed from their family were more likely to have high levels of psychological distress (38%) than those not removed (28%).

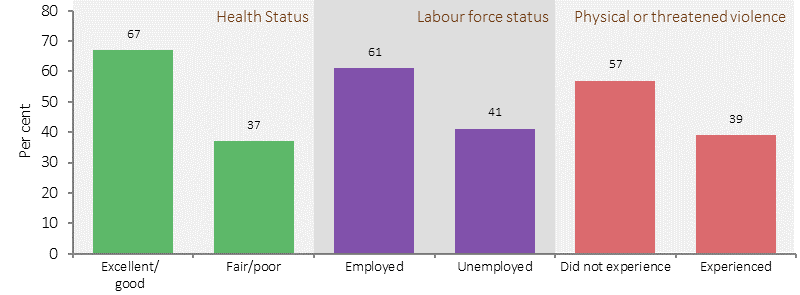

The 2014–15 Social Survey included an overall life satisfaction measure with a scale from 0 ‘not at all satisfied’ to 10 ‘completely satisfied’ (ABS, 2016e)(ABS, 2016). More than half (53%) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported an overall life satisfaction rating of 8 or above (52% in non-remote areas and 58% in remote areas). A high rating of 10 was more common in remote areas (27%) than non-remote areas (14%). A high rating of 8 or above was associated with self-assessed excellent or very good health (67%) compared with 37% of those with fair/poor health; being employed (61%) compared with being unemployed (41%); not experiencing violence in the last 12 months (57%) compared with those who did (39%); being able to get support in a time of crisis compared with those who could not (55% and 38%, respectively).

Based on analysis of the 2008 Social Survey and the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA), 53% of Indigenous Australians reported that they had ‘been a happy person’ all or most of the time in the previous four weeks compared with 61% of non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW, 2014h). Higher levels of education and being employed were associated with higher levels of wellbeing (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). However, there was a weaker link between income and positive wellbeing for Indigenous Australians in remote areas compared with non-remote areas. Further analysis of HILDA results in the period 2001–12 showed that life satisfaction ratings peaked in 2003 for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, but declined significantly after that point for Indigenous Australians only (Manning et al, 2016). In a recent multivariate analysis of data from national health and social surveys of the Indigenous Australian population, conducted between 2002 and 2012–13, employment status and housing tenure were shown to be significantly associated with a range of health and wellbeing outcomes. As education levels have increased for Indigenous Australians, the association of education with health and wellbeing has weakened (Crawford & Biddle, 2017).

Psychological distress

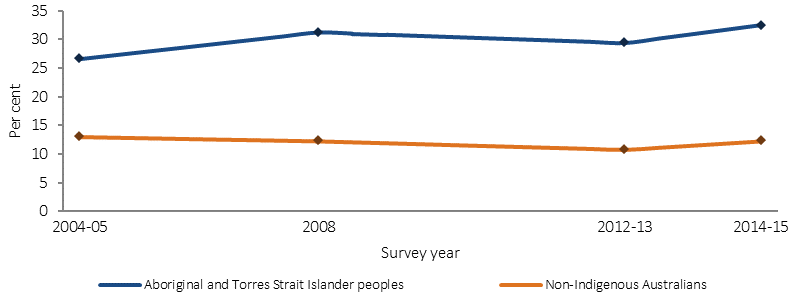

Based on the 2014–15 Social Survey, most (67%) Indigenous adults aged 18 years and over had low/moderate levels of psychological distress and 33% had high/very high levels. There was a significant 6 percentage point increase in those reporting high/very high levels of psychological distress between 2004–05 (27%) and 2014-15.

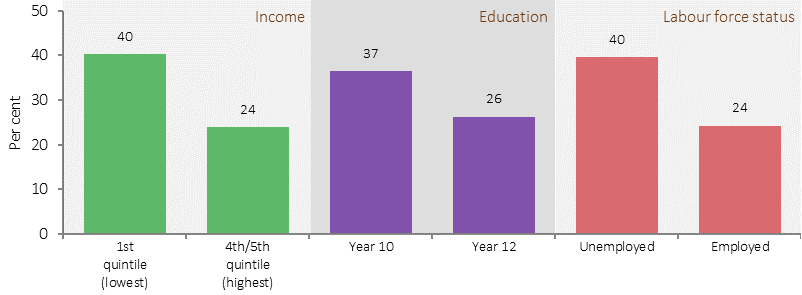

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, Indigenous adults were 2.6 times as likely as non-Indigenous adults to experience high/very high psychological distress. For Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over, females (39%) were significantly more likely than males (26%) to report high/very high levels of psychological distress. There was no difference by remoteness. Those with high/very high psychological distress levels were more likely to have lower income, lower educational attainment and higher unemployment.

Life stressors

In 2014–15, more than two-thirds (68%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples said they had experienced one or more stressors in the last 12 months (ABS, 2016e). The most common stressors reported were the death of a family member or close friend (28%), inability to get a job (18%), serious illness (12%), and mental illness (10%).

Indigenous Australians living in both non-remote and remote areas reported on average 2 stressors. Indigenous Australians living in non-remote areas were more likely to report stressors due to serious illness, mental illness, discrimination and family stressors while those living in remote areas were more likely to report stressors such as the death of a family member or close friend, overcrowding or alcohol problems. Research has shown that parental stress caused by factors such as unemployment and financial problems is associated with emotional or behavioural difficulties in children and decreased utilisation of health services for the child's needs (Ou et al, 2010; Strazdins et al, 2010).

Depression and racism

In 2014–15, 35% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over felt that they had been treated unfairly in the last 12 months because they were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Rates of psychological distress were higher for this group (44%) than for those who reported that they had not been treated badly (27%). Research in the NT has found a significant association between interpersonal racism and depression among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. Lack of control, stress, negative social connections and reactions to racism such as feeling ashamed or powerless were each identified in the relationship between racism and depression (Paradies & Cunningham, 2012). A study of 755 Aboriginal Victorians also found an association between reported racism and psychological distress (Kelaher et al, 2014).

Social and emotional wellbeing of children

In 2014–15, 67% of Indigenous children aged 4–14 years were reported to have experienced one or more stressors in the last 12 months, with death of family/friend the most commonly reported stressor (25%), followed by being scared or upset by an argument or someone’s behaviour and/or trouble keeping up with school work (both 23%) (ABS, 2016e). In addition, 40% of Indigenous children aged 4–14 years had been bullied at school and 9% had been treated unfairly at school because they were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) showed that 23% of Indigenous children were at high risk of clinically significant emotional and behavioural difficulties (Department of Families, 2012). Factors impacting on surveyed children’s social and emotional difficulties scores, were a close family member having been arrested, been in jail or had problems with the police; the children being cared for by someone else for at least a week as opposed to remaining constantly with their regular carers; and children being scared by other people’s behaviour. These intra-family factors were more significant than many commonly assumed social factors, such as illness, housing problems and money worries (Department of Families, 2013; 2015).

Mental health conditions

Mental health and substance use disorders combined were the leading cause of total disease burden for Indigenous Australians, representing 19% of the burden; and 14% of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in 2011 (AIHW, 2016f). Anxiety disorders represented 23% of the total burden from mental and substance use disorders followed by alcohol use disorders (22%), depressive disorders (19%), schizophrenia (8%) and drug use disorders (6%). Non-fatal burden predominated for mental health and substance use (97%); burden was highest in younger age groups (44 years and under); and higher for males (56%) than for females (44%).

Mental health related conditions accounted for 3% of deaths among Indigenous Australians over the period 2011–15 in NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined. Of these deaths 64% were for organic mental disorders (injury or non-psychiatric illness affecting the brain) and 23% were for mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use. After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, Indigenous Australians died from mental health-related conditions at a rate 1.1 times the non-Indigenous rate.

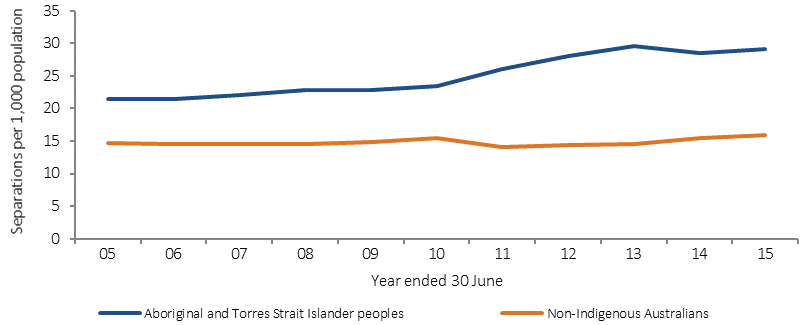

In the period July 2013 to June 2015, mental health related conditions were the principal reason for 7% of hospitalisations (excluding dialysis) for Indigenous Australians. Indigenous men were hospitalised for mental health related conditions at 2.1 times the rate of non-Indigenous males, and Indigenous females at 1.5 times the rate for non-Indigenous females. Between 2004 – 05 and 2014–15, there was a 56% increase in hospitalisations for mental health related conditions among Indigenous females, and a 36% increase for Indigenous males in the six jurisdictions with adequate data for trend reporting (NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined). Rates among non-Indigenous Australians remained static over this period, resulting in a 142% increase in the difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous rates.

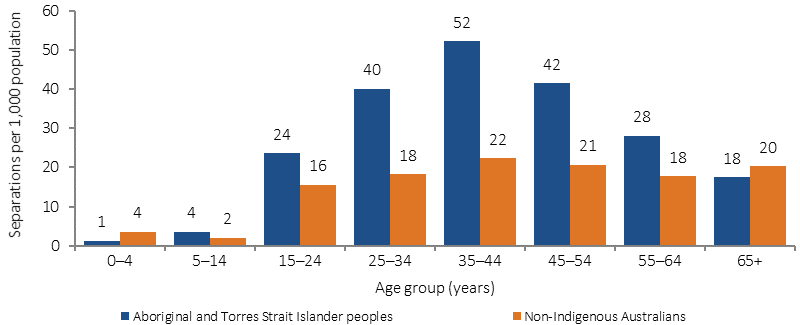

The most common reasons for mental health related hospitalisations were mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (38% of episodes), schizophrenia (22%), neurotic, stress-related disorders (15%), and mood disorders (14%). Indigenous hospitalisation rates for mental health related issues were highest in the 25–54 year age groups. Rates were lowest in very remote (23 per 1,000 population) and inner regional areas (24 per 1,000 population) and were highest in remote areas (33 per 1,000 population). Rates varied between jurisdictions. The highest rate was in SA (44 per 1,000).

In 2014–15, 29% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported having a long-term mental health condition (ABS, 2016). Of those aged 18 years and over reporting a mental health condition, the main types of conditions were: depression (72%); anxiety (65%); behavioural or emotional problems (25%); and harmful use of drugs or alcohol (17%). Mental health conditions were less likely to have been reported by Indigenous males (25%) than females (34%); and young people (22%) than those in older age groups (ranging from 30% to 35%). Indigenous Australians with a mental health condition were more likely to be a daily smoker (46%) and to have used substances in the last 12 months (39%) than were people with no long-term health conditions (39% and 29% respectively). Those with a mental health condition were more likely to report experiencing one or more stressors (84%) compared with those had no long-term health conditions (60%). Those with a mental health condition were less likely to have had daily face-to-face contact with family or friends outside their household (36%) than those with no long-term health conditions (52%). They were more likely to have experienced physical violence in the last 12 months (20%) than were people with other long-term health conditions (9%) or no long-term health condition (12%). Those with a mental health condition were more likely to have experienced problems accessing health services (23%) than were people with other long-term health conditions (13%) or no long-term health conditions (10%).

Around 11% of all problems managed by GPs among Indigenous patients were mental health related (GP survey data 2010–15). Depression and anxiety were the leading problems managed for both Indigenous and other Australian patients. After adjusting for differences in the age profile of the two populations, GPs managed mental health related problems for Indigenous patients at 1.2 times the rate for other Australians. Rates of tobacco, alcohol and drug abuse problems for Indigenous patients were 2–3 times the rates for other Australians.

Suicide

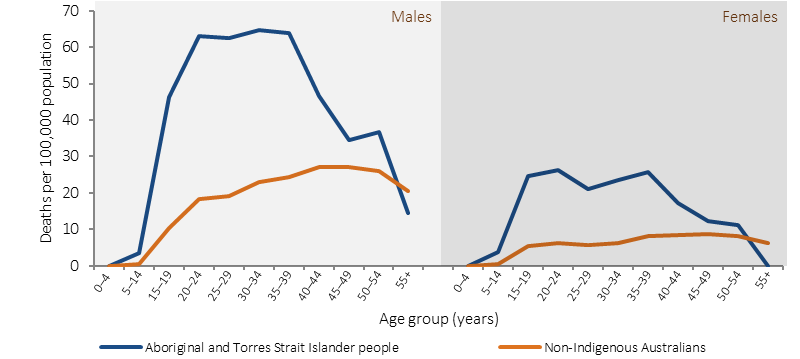

For the period 2011–15, among Indigenous Australians in the jurisdictions with adequate data quality (NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined), there were 690 suicides (on average 138 suicides per year). This accounted for approximately 5% of deaths among Indigenous Australians at a rate of 23 per 100,000. Indigenous males accounted for 71% of suicides in that population. After adjusting for differences in the age profile of the two populations, the Indigenous suicide rate was twice the rate for non-Indigenous Australians. Rates for Indigenous males were highest among those aged 30–34 years (65 per 100,000 population), while rates for non-Indigenous males were highest among those aged 40–44 and 45–49 years (both 27 per 100,000). Rates for Indigenous females were highest among those aged 20–24 and 35–39 years (both 26 per 100,000), while for non-Indigenous females rates were highest among those aged 45–49 years (8.7 per 100,000). During 2011–15, the majority (87%) of Indigenous suicides occurred before 45 years of age. This pattern is different among non-Indigenous Australians, with 50% of suicides occurring at less than 45 years of age. After the age of 54, the suicide rates for Indigenous Australians are lower than those for non-Indigenous Australians. A study in WA found that Aboriginal mothers were 3.5 times as likely to commit suicide as non-Indigenous mothers (Fairthorne et al, 2016).

There was a 32% increase in Indigenous suicide rates from 1998 to 2015 (NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT combined). For non-Indigenous Australians there was a 34% decline from 1998 to 2006 and a 22% increase from 2006 to 2015. WA had the highest Indigenous suicide rate in 2015 (41 per 100,000). Kimberley had the highest Indigenous suicide rate (61 per 100,000) of all IAS Regions and was 3 times the national Indigenous suicide rate in 2009–13. Research in the NT has shown that the Indigenous suicide rate increased significantly between 1981 and 2002 (Measey et al, 2006). More recent data from the NT shows no significant change between 2001 and 2015.

Between July 2013 and June 2015 there were 4,365 hospitalisations among Indigenous Australians for intentional self-harm, representing 1% of Indigenous hospitalisations over this period. Rates were higher for Indigenous females (3.8 per 1,000 population) compared with males (2.5 per 1,000), and were higher in remote areas (3.9 per 1,000) compared with other areas (3.3 per 1,000 in major cities, 2.9 per 1,000 in regional areas and 2.8 per 1,000 in very remote areas). After adjusting for differences in population age structures, Indigenous Australians were hospitalised for self-harm at 2.7 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

In 2001–02, as part of the WAACHS, 16% of young people aged 12–17 years reported suicidal thoughts (20% of girls compared with 12% of boys). The proportion of Aboriginal children who reported suicidal thoughts was significantly higher among those who smoked regularly, used cannabis, drank to excess, were exposed to some form of family violence, or who had a friend who had attempted suicide. A large longitudinal study in New Zealand found that young suicide attempters were significantly more likely to have persistent mental health problems (e.g. depression, substance dependence) in middle age when compared to non-attempters. They were also more likely to have physical health problems (e.g. metabolic syndrome); engage in more violence (e.g. violent crime, intimate partner abuse); and needed more social support (e.g., long-term welfare receipt). Furthermore, they reported being lonelier and less satisfied with their lives (Goldman-Mellor et al, 2014).

Figures

Figure 1.18-1

Proportion of people aged 18 years and over reporting high/very high levels of psychological distress (age-standardised), by Indigenous status, 2004–05, 2008, 2012–13 and 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of the 2012–13 AATSIHS and 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 1.18-2

Proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reporting high life satisfaction ratings, by selected characteristics, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of the 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 1.18-3

Proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reporting high/very high levels of psychological distress, by selected social factors, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of the 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 1.18-4

Mortality from suicide rates per 100,000, by Indigenous status, sex and age group, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT, 2011–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of National Mortality Database

Figure 1.18-5

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for mental health related conditions, by Indigenous status, 2004–05 t0 2014–15

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.18-6

Age-specific hospitalisation rates for mental health related conditions, by Indigenous status, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Implications

The policy responses to social and emotional wellbeing need to be multidimensional and involve a wide range of stakeholders. Strategies that build on the strengths, resilience and endurance within Indigenous communities and recognise the important historical and cultural diversity within communities are recommended (SHRG, 2004; Dudgeon et al, 2014a). Recent suicide prevention studies have identified the need to focus on protective factors, such as community connectedness, strengthening the individual and rebuilding family, as well as culturally based programmes(Tighe & McKay, 2012; Dudgeon et al, 2012; AIHW & AIFS, 2013; Clifford et al, 2012; Cox et al, 2014; Ridani et al, 2015).

The Healing Foundation funding agreement (2015–18) allocates $14 million for healing programs. This includes community healing activities, men’s healing projects, and healing projects for members of the Stolen Generations and their families. Of the 6,300 people who participated in Healing projects in 2014–15, 73% of children and young people reported an improvement in social and emotional wellbeing, 85% of Stolen Generations members reported having an increased sense of belonging and connection to culture and 85% of participants reported that they can now better manage the impacts of trauma. An additional $3.6 million has been allocated for trauma-informed Indigenous healing education and workforce development, and capacity building and knowledge creation for service providers of healing programs.

The Indigenous Advancement Strategy—Safety and Wellbeing programme provides funding for strategies to enhance community safety and support Indigenous wellbeing. In 2015–16 this included funding of $40 million for social and emotional wellbeing services and workforce support. This included Link-Up services to provide counselling, family tracing and reunion services to members of the Stolen Generations and two Indigenous suicide prevention projects run by the University of Western Australia. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Evaluation Project has identified success factors for suicide prevention and developed a suite of community tools (Dudgeon et al, 2016). The National Critical Response Project has been allocated $10 million over three years from 2016–17 to help determine the immediate needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities who have experienced traumatic events such as suicide and improve critical response services and local community capacity to meet these needs. It commenced in January 2017 and builds on the pilot project in WA. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Advisory Group is providing advice to Government on strategic and practical actions to prevent suicide and improve the mental health and social and emotional wellbeing.

Funding for Indigenous specific suicide prevention activity is an ongoing component of Commonwealth suicide prevention investment, as part of the new direction in suicide prevention outlined in the Government’s response to the National Mental Health Commission’s Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Approximately $5.6 million per annum is allocated to Primary Health Networks (PHNs) for the delivery of culturally appropriate suicide prevention services for Indigenous Australians, with approximately $0.7 million per annum to be allocated for a National Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention.

In addition, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander chapter in the Fifth National Mental Health Plan and a revised National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing are being developed.

Various state/territory initiatives are being undertaken, including the multi-award winning Alive and Kicking Goals project in the Kimberley, which is wholly owned and led by young Aboriginal women and men. The project aims to reduce the high suicide rate among Indigenous youth through peer education workshops, one-on-one mentoring, and counselling.

Through SA Health brokerage funding, access to Traditional Healers is available at no cost to Aboriginal patients through referrals from clinicians and health practitioners. Traditional Healers play an important role in the healing process for Aboriginal people and influence and support the positive management of Aboriginal people’s emotional, spiritual and physical wellbeing. The Traditional Healers programme supports healers to continue practising an important aspect of Aboriginal culture.