3.10 Access to mental health services

Page content

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience higher rates of mental health issues than other Australians with deaths from suicide twice as high; hospitalisation rates for intentional self-harm 2.7 times as high; and rates of high/very high psychological distress 2.6 times as high as for other Australians (see measure 1.18). While Indigenous Australians use mental health services at higher rates than other Australians, it is hard to assess whether this use is as high as the underlying need.

Social, historical and economic disadvantage contribute to high rates of physical and mental health problems, high adult mortality, high suicide rates, child removals and incarceration rates, which in turn lead to higher rates of grief, loss and trauma (see measure 1.18). Most mental health services address mental health conditions once they have emerged rather than addressing the underlying causes of distress. Even so, early access to effective services can help diminish the effects of these problems and help restore people’s emotional and social wellbeing.

Mental health care may be provided by specialised mental health care services (e.g. private psychiatrists, and specialised hospital, residential or community services), or by general health care services that supply mental health related care (e.g. GPs and Indigenous primary health care organisations).

Findings

In the 2012–13 Health Survey, 27% of Indigenous Australian adults with high/very high levels of psychological distress had seen a health professional about their distress in the previous 4 weeks. Rates were higher for females (30%), and those living in non-remote areas (29%).

The latest available data on Medicare-subsidised mental health care services, (provided by consultant psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, GPs and allied health professionals) are from 2014–15. In that year, 10% of Indigenous Australians accessed Medicare-subsidised clinical mental health care services, as did 9% of non-Indigenous Australians (SCRGSP, 2017).

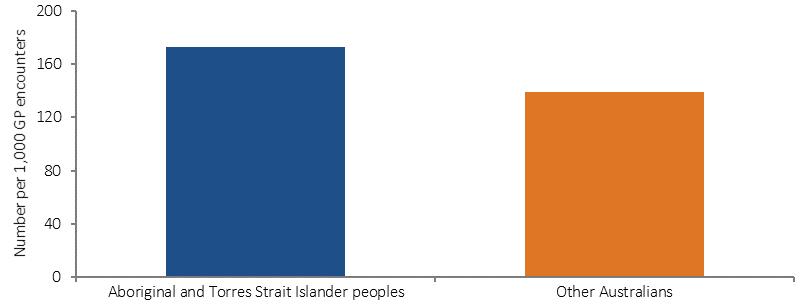

Based on GP survey data (2010–15), 11% of all problems managed by GPs among Indigenous patients were related to mental health. Depression (47 per 1,000 encounters) and anxiety (23 per 1,000 encounters) were the main mental health related problems managed. After adjusting for differences in the age profiles of the two populations, GPs managed mental health problems for Indigenous Australians at 1.2 times the rate for other Australians.

Most of the 203 Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care (PHC) organisations provided care in relation to social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) and mental health issues. As at 31 May 2015, these organisations employed 440 FTE SEWB staff (49% Indigenous). In 2014–15, these staff provided 189,900 client contacts. Depression (76%), anxiety/stress (71%), grief and loss issues (70%), family/relationship issues (63%) and family/community violence (56%) were the most common SEWB related issues managed in terms of staff time and organisational resources (AIHW, 2016o).

In 2014–15, there were 97 organisations funded by the Commonwealth to provide SEWB or Link Up counselling services to Indigenous Australians (82 of which were also funded for PHC and included above). Within these organisations, 221 counsellors provided about 100,150 client contacts to over 21,100 clients (an average of 4–5 contacts for each client) (AIHW, 2016o).

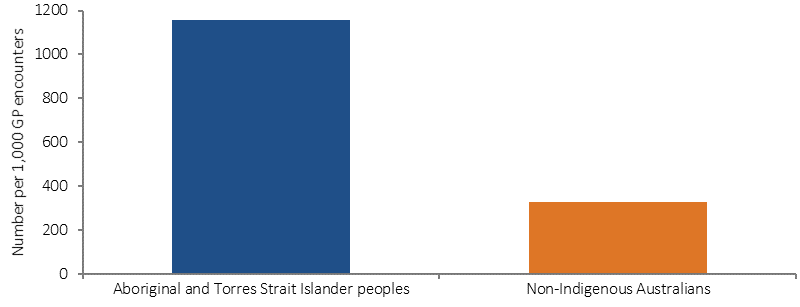

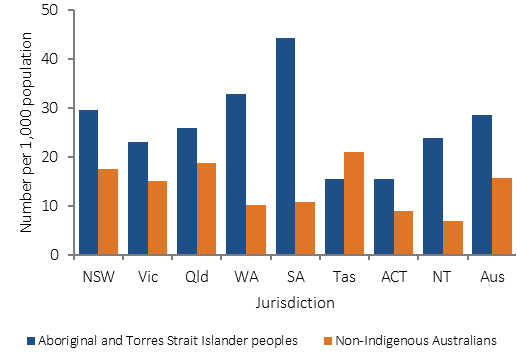

State/territory-based specialised community mental health services reported 744,900 service contacts for Indigenous clients in 2014–15 (10% of client contacts). Rates for Indigenous Australians were 4 times the rates for non-Indigenous Australians and were higher across all age groups, particularly those aged 25–44 years. Community mental health care contact rates for Indigenous Australians were highest in the ACT (2,604 per 1,000) and lowest in Tas (293 per 1,000). The rate of residential mental health care episodes in the same period was 62 per 100,000 for Indigenous Australians—1.9 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Access to specialist psychiatry in rural and remote Australia is particularly problematic (Hunter, E, 2007). In 2014, for clinical psychologists, there were 31 FTE per 100,000 people in remote/very remote areas compared with 102 per 100,000 in major cities.

In 2015–16, Indigenous Australians were less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to have claimed through Medicare for psychologist care (133 compared with 200 per 1,000) and also psychiatric care (52 compared with 97 per 1,000). In addition, Indigenous Australians utilised the Access to Allied Psychological Services programme at 3.5 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW, 2016k).

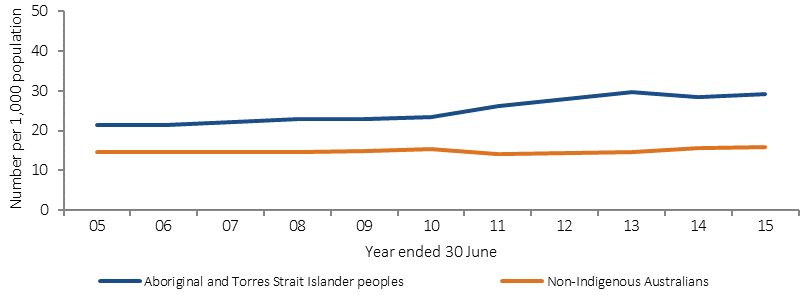

In the two years to June 2015, the hospitalisation rate for mental health issues for Indigenous males was 2.1 times the rate for non-Indigenous males, and the rate for Indigenous females was 1.5 times the rate for non-Indigenous females. Rates were highest among those aged 35–44 years (52 per 1,000 population) which was 2.3 times the non-Indigenous rate.

Between 2004–05 and 2014–15 (for NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT), hospitalisation rates for mental health related conditions significantly increased for Indigenous Australians—by 56% for females, 36% for males and 46% overall.

Hospitalisations for mental health care can be divided into two main categories: ambulatory-equivalent (comparable to care provided by community mental health care services) and admitted patient care. In the two years to June 2015, ambulatory-equivalent separation rates were lower for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians where separations involved specialised psychiatric care (rate ratio of 0.3) and 3 times the rate for separations without specialised psychiatric care. For admitted patient mental health care, separation rates for Indigenous Australians were twice as high with specialised psychiatric care and 3.2 times as high without, compared with non-Indigenous patients.

The rate of available psychiatric beds in public psychiatric hospitals ranged from 9.5 per 100,000 in major cities to 1.3 per 100,000 in outer regional areas and none in remote and very remote areas. For mental health care provided in hospitals, the average length of stay was 10 days for Indigenous patients and 12 days for non-Indigenous Australians. In 2013–15, 5% of all emergency department presentations for Indigenous patients were mental health related, as were 3% for other patients (AIHW, 2016j).

Barriers to accessing mental health services include perceived potential for unwarranted intervention from government organisations, long wait times (more than one year), lack of inter-sectoral collaboration and the need for culturally competent approaches including in diagnosis (Williamson et al, 2010; McGough et al, 2017).

In a Qld study (Hepworth et al, 2015), culturally safe mental health services were integrated into primary health care by including a psychologist and social worker as core members of the primary health team. This resulted in additional client services and referrals. Key themes identified for increasing access were: responsiveness to community needs; trusted relationships; and shared cultural background and understanding.

In 2014–15, Indigenous Australians with psychiatric disability used both residential and non-residential disability support services at more than twice the rate of non-Indigenous Australians.

In 2014–15, the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Specialist Homelessness Services clients with a current mental health issue was more than 6 times that of non-Indigenous Australians (1,451 and 227 per 100,000 population respectively) (AIHW, 2017b).

Figures

Figure 3.10-1

Age-standardised mental health related problems managed by GPs per 1,000 encounters, by Indigenous status of the patient, April 2010–March 2015

Source: University of Sydney analysis of BEACH data

Figure 3.10-2

Age-standardised community mental health care service contacts per 1,000 population, by Indigenous status, 2014–15

Source: AIHW analysis of National Community Mental Health Care Database

Figure 3.10-3

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for mental health related conditions, by Indigenous status, 2004–05 to 2014–15

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 3.10-4

Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for mental health related conditions, by Indigenous status and jurisdiction, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Implications

These findings suggest that Indigenous Australians are accessing primary care level mental health services more readily than specialist services, particularly in comparison to non-Indigenous Australians.

In response to the Mental Health Review in November 2015, the Australian Government committed $85 million over three years to increase culturally sensitive, integrated mental health services specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The funding is being provided to Primary Health Networks to plan, commission and implement mental health services joining up closely related services such as SEWB, suicide prevention, and alcohol and other drug treatment.

The funding complements other initiatives announced under the Government’s mental health reform package which are also accessible to Indigenous Australians. These include integrated team care packages tailored to individual needs, suicide prevention activities focused on local needs, coordinated services for children and youth to achieve better mental health promotion, and prevention and early intervention.

Improving the mental health system and outcomes for people with mental illness can only be done in partnership with consumers, carers, mental health stakeholders and state and territory governments. The Commonwealth is committed to continued consultation and engagement as reforms are implemented.

Commonwealth and state and territory governments are developing the Fifth National Mental Health Plan, which includes information specific to meeting the needs of Indigenous Australians. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework is also being renewed to better acknowledge the importance of culture and identity to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous Australians.

Other mental health care and suicide prevention initiatives are detailed in measure 1.18 and the Policies and Strategies section.