2.01 Housing

Page content

Why is it important?

Housing circumstances including overcrowding, tenure type and homelessness both directly and indirectly influence health outcomes (Andersen et al, 2016). The effects of overcrowding occur in combination with other environmental health factors such as unsafe, unclean and poor quality housing infrastructure (see measure 2.02); exposure to toxins and allergens such as smoking indoors (see measure 2.03); as well as increased risk of injury within the home (Bailie, RS & Wayte, 2006; Brackertz, 2016; Nganampa Health Council et al, 1987).

There are complex relationships between housing circumstances, health and socio-economic factors such as education, income and employment (Thomson, H et al, 2013). Overcrowding, insecure housing tenure, and homelessness adversely impact on school attendance and attainment (Brackertz, 2016; Biddle, 2014a); and housing tenure and affordability have been found to have negative impacts on childrens’ physical health, learning outcomes and social and emotional wellbeing (Dockery et al, 2013). Biddle (2011) found structural problems and missing facilities (measure 2.02) had a greater association with wellbeing outcomes than overcrowding and tenure type.

Homelessness is linked with experiences of domestic violence, alcohol and drug problems, financial hardship and unmet need for public housing (Graham, D et al, 2014; Memmott et al, 2012).

Findings

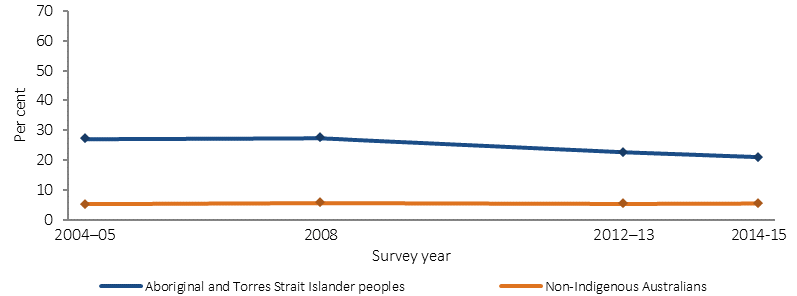

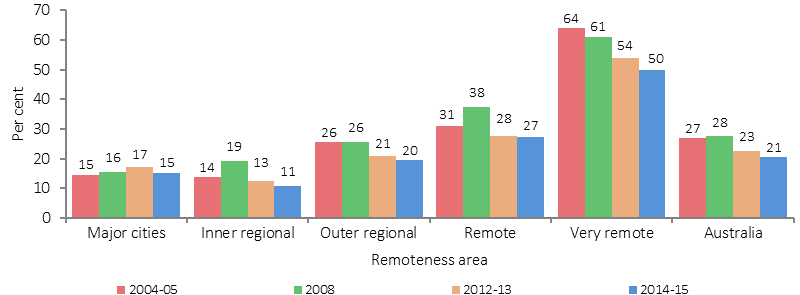

The 2014–15 Social Survey collected data on a variety of housing characteristics, including overcrowding. Households requiring at least one additional bedroom are defined as overcrowded according to the Canadian National Occupancy Standard. In 2014–15, 21% of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons were living in overcrowded households compared with 6% of non-Indigenous Australians. A large number of Indigenous Australians in both non-remote areas (82,100) and remote areas (59,400) experienced overcrowding, however it was more common in remote areas; 41% of Indigenous Australians in remote areas lived in overcrowded households, compared with 15% in major cities. In 2014–15, overcrowding was higher in the NT (53%) than any other state or territory (at least double the rate of overcrowding in any other jurisdiction). The next highest proportion was WA (25%). Of those living in remote areas, NT had a higher proportion of overcrowding (59%) than those living in remote areas in other states and territories (43% in SA, 34% in WA and 31% in Qld). Nationally, between 2008 and 2014–15, the proportion of Indigenous Australians living in overcrowded households declined by 6.8 percentage points (from 27.5% to 20.7%) and the gap narrowed as non-Indigenous rates remained steady at around 6%.

In 2014–15, 7% of Indigenous adults reported overcrowding as a stressor, down from 21% in 2002. This change was greatest in very remote areas.

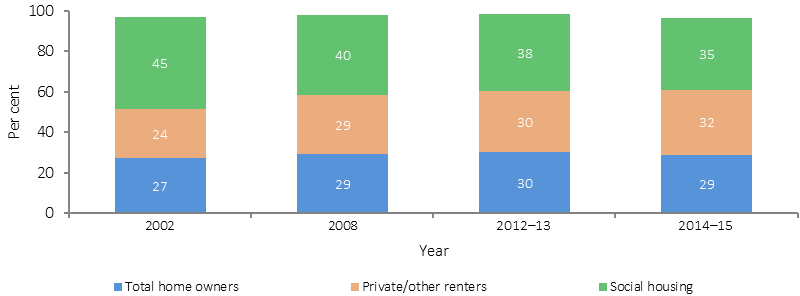

In 2014–15, 29% of Indigenous adults lived in homes that were owned or being purchased by a household member (referred to here as home owners). This comprised 10% who owned their homes outright and 19% with a mortgage. A further 35% lived in a property rented through social housing (provided by state/territory governments and community sectors to assist people who are unable to access private rentals); and 32% lived in private rentals. In contrast, 69% of non-Indigenous adults were home owners. Since 2002, the rate of Indigenous home ownership has remained stable, while renting through private or other arrangements has increased by 8 percentage points. Renting through social housing has declined between 2002 and 2014–15 (from 45% to 35%).

Housing tenure patterns are influenced by a range of factors including socio-economic status and Indigenous land arrangements in some remote areas (where there is communal tenancy arrangements). In 2014–15, home ownership by Indigenous adults was higher in non-remote areas (34%) than remote areas (12%) reflecting the barriers to home ownership in remote areas. In remote areas, the largest category of housing was rental through social housing (68%), compared with 26% in non-remote areas. Indigenous home ownership was highest in Tasmania (53%) and lowest in the NT (11%).

In 2014–15, Indigenous Australians were more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have experienced homelessness (29% compared with 13%). In 2014–15, 41% of Indigenous Australians had experienced not having a permanent place to live. The main reasons were family/friend/relationship problems (17%) and tight housing/rental market/not enough housing (7%).

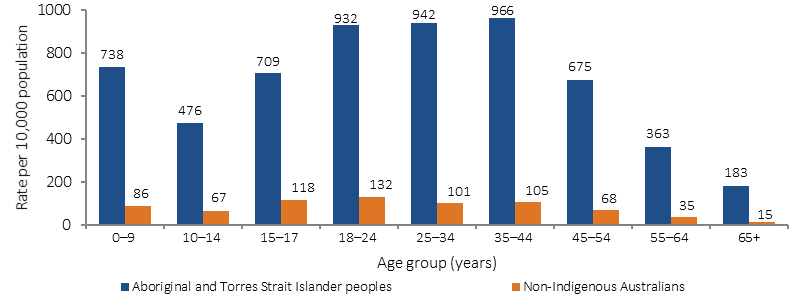

In 2011, Indigenous Australians accounted for 28% of the homeless population (based on the ABS definition of homelessness). Three-quarters of Indigenous homelessness is due to living in severely crowded dwellings while the remainder includes people living in supported accommodation for the homeless (12%); people in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out (6%); and people staying temporarily in other households (4%). In 2011, 42% of Indigenous homeless people were under 18 years (AIHW, 2014i). In 2014–15, 24% of those accessing specialist homelessness services were Indigenous Australians. The rate of service use for Indigenous clients was 8.7 times the non-Indigenous rate (693 compared with 80 per 10,000). The majority of Indigenous clients were women (62%) and almost a quarter (23%) of all Indigenous clients were children aged 0–9 years. Domestic/family violence was the main reason (24%) for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous clients seeking specialist homelessness services. Indigenous clients (34%) were more likely than non-Indigenous clients (24%) to be presenting as a single person with children. Over a third (36%) of Indigenous clients were living in short term temporary accommodation prior to accessing homelessness support, and 21% of Indigenous males were living without shelter prior to accessing support.

Figures

Figure 2.01-1

Proportion of persons living in overcrowded households, by Indigenous status, 2004–05, 2008, 2012–13 and 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS and 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 2.01-2

Proportion of Indigenous Australians living in overcrowded households, by remoteness, 2004–05, 2008, 2012–13 and 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS and 2014–15 NATSISS

Figure 2.01-3

Use of specialist homelessness services, by Indigenous status, and age (crude rate per 10,000 population), 2014–15

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection

Figure 2.01-4

Proportion of Indigenous persons 18 years and over, by tenure type, 2002, 2008, 2012–13 and 2014–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS and 2014–15 NATSISS

Implications

While there have been improvements in overcrowding and home ownership for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households, outcomes for Indigenous Australians remain lower than those for non-Indigenous Australians. The National Affordable Housing Agreement (NAHA) (AIHW, 2014e) aims to ensure that all Australians have access to affordable, safe and sustainable housing that contributes to social and economic participation. Two of the six NAHA outcomes focus specifically on Indigenous Australians: that Indigenous Australians have the same housing opportunities (homelessness services, housing rental, housing purchase and access to housing through an efficient and responsive housing market) as other Australians; and that Indigenous Australians have improved housing amenity and reduced overcrowding.

The NAHA is supported by the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (NPAH) and the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH). Specific NPAH initiatives aimed at addressing Indigenous homelessness include youth facilities, domestic and family violence support and outreach to rough sleepers.

The NPARIH was designed to help address significant overcrowding, homelessness, poor housing condition and severe housing shortages in remote Indigenous communities and committed $5.5 billion over ten years to achieve this. The NPARIH is expected to deliver up to 4,200 new houses by 2018 and has exceeded its target of rebuilding or refurbishing around 4,876 existing houses in remote Indigenous communities by 2014. The Australian Government provides direct support for home ownership through financial literacy support and assisted loans through Indigenous Business Australia.

The NPARIH was replaced by the National Partnership on Remote Housing (NPRH) on 1 July 2016. The NPRH provides $774 million from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018 to help maximise the Commonwealth investment in remote Indigenous housing and ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have access to safe and adequate housing. The NPRH will continue to deliver new houses and refurbishments but will also focus on the achievement of reform. Under the NPRH, the Australian Government in partnership with state and territory governments, is:

- improving property and tenancy management delivery so houses last longer

- increasing employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians

- encouraging higher levels of engagement of Indigenous businesses in the delivery of housing and housing services

- removing barriers standing in the way of home ownership opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, particularly those from remote communities.

The NPRH includes a commitment to undertake a review of investment in remote housing. The review commenced in 2016 and is required to be completed at least 12 months prior to the expiry of the NPRH. The review will inform future government policy directions for remote housing when the NPRH concludes.