1.08 Cancer

Page content

Why is it important?

Cancer is a group of diseases in which abnormal cells proliferate and spread. These cells can form a malignant tumour that can invade and damage the area around it and spread to other parts of the body through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system. If the spread of these tumours is not controlled, they may result in death. The effectiveness of treatment and survival rates can vary between different cancers and patients (AIHW, 2017a).

Risk factors for high fatality cancers remain prevalent in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, including smoking, risky drinking and poor diet (Condon et al, 2003; AIHW & Cancer Australia, 2013). Indigenous Australians have a higher incidence of fatal, screen-detectable and preventable cancers and are diagnosed at more advanced stages, and often with more complex comorbidities (Cunningham et al, 2008). Compared with non-Indigenous Australians diagnosed with the same cancer, Indigenous Australians are doubly disadvantaged because they are usually diagnosed later with more advanced disease, are less likely to have treatment, and often have to wait longer for surgery than non-Indigenous patients (Hall, SE et al, 2004; Valery et al, 2006).

Findings

Cancer was responsible for 9% of the Indigenous burden of disease and 9% of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in 2011 (AIHW, 2016f). Indigenous Australians experienced 1.7 times the burden due to cancer than non-Indigenous Australians; 2.4 times for lung cancer. Lung (24%), bowel (8%), liver (7%), breast (7%) and mouth and pharyngeal (6%) cancers accounted for half (51%) of the cancer burden among Indigenous Australians. The biggest risk factor was tobacco use (39%) and 97% of the cancer burden was due to early death. Between 2003 and 2011 there was a 6% increase in burden due to cancer for Indigenous Australians, mainly due to deaths from liver and lung cancer.

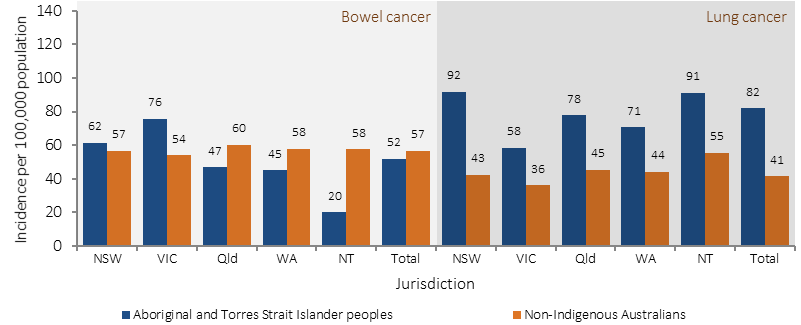

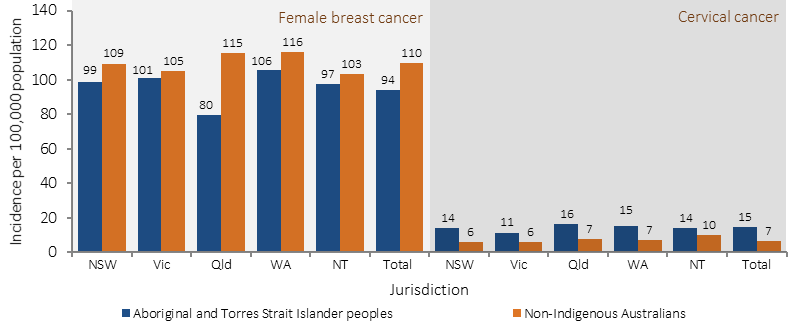

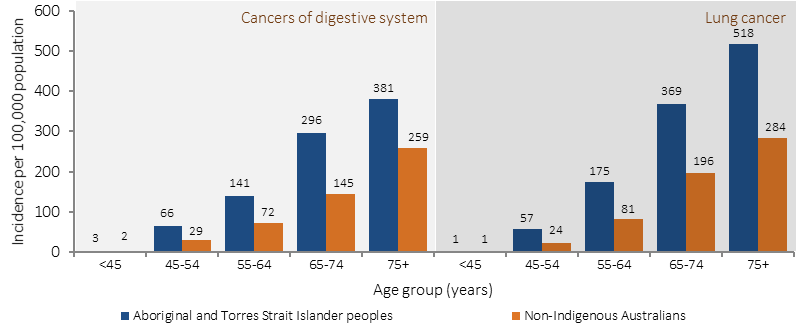

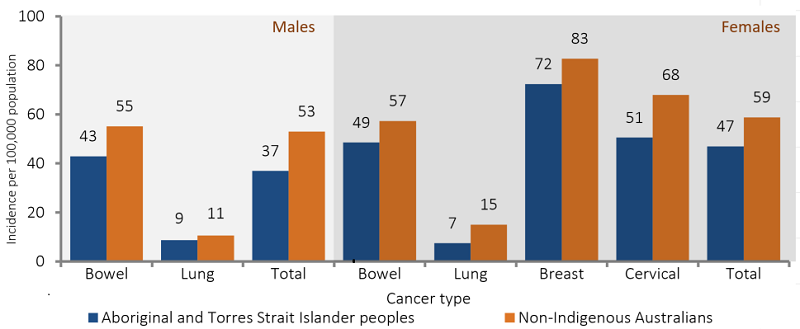

In 2008–12, cancer incidence was slightly higher for Indigenous Australians (484 per 100,000) than for non-Indigenous Australians (439 per 100,000) (age-standardised) in the jurisdictions with data of adequate quality (NSW, Vic, Qld, WA and the NT combined). For Indigenous Australians, rates for lung cancer, digestive system cancer (excluding bowel) and cervical cancer were higher and rates for bowel cancer and breast cancer in females were lower compared with non-Indigenous Australians (age-standardised). Among Indigenous Australians, incidence rates were higher in younger age groups than for non-Indigenous Australians. Higher rates of cancer incidence were evident from 45 years onwards. In 2004–12, the 5-year crude cancer survival rate for Indigenous Australians was lower for both Indigenous males (37%) and females (47%) compared with non-Indigenous males (53%) and females (59%). A study of cancer registry data in NSW found a large number of cases with missing Indigenous status. Once imputed, an additional 12–13% of Indigenous cancer cases were identified (Morrell et al, 2012).

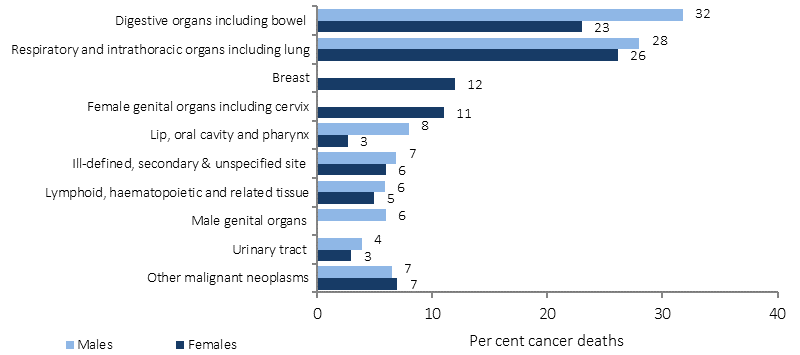

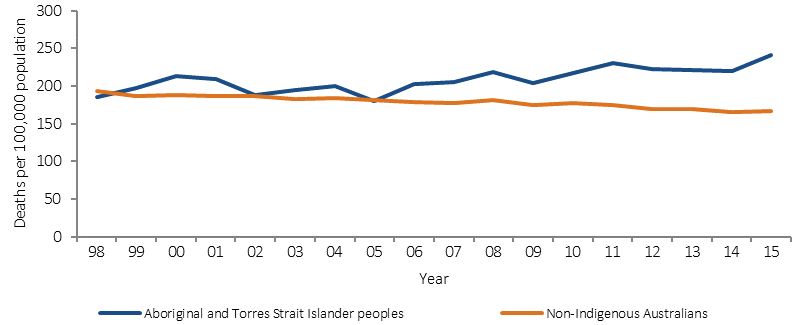

Cancer was the second leading cause of death among Indigenous Australians, accounting for 21% of deaths during the period 2011–15, in NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined. Over this period, cancers of the digestive organs and respiratory organs (including lung) were the most common causes of cancer death among Indigenous Australians (28% and 27% respectively). In 2011–15, after adjusting for differing population age structures, Indigenous Australians were 1.4 times as likely to die from cancer as non-Indigenous Australians. Cancer was the third leading cause of the gap in death rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (15% of the gap). The largest gaps between the two populations were in cancers of the respiratory organs, particularly bronchus and lung cancer, followed by cancers of the digestive organs. Over the period 1998 to 2015, there has been a significant increase in cancer death rates for Indigenous Australians (21%) and a significant decline for non-Indigenous Australians (13%); therefore the gap in cancer deaths between the two populations has widened.

Research suggests that survival rates among non-Indigenous patients are up to 50% greater than those for Indigenous patients within the first 12 months of diagnosis, dropping to a similar survival rate 2 years after diagnosis. There was no evidence that the rate of five-year survival varied by remoteness or socio-economic status for Indigenous Australians (Cramb, 2012). Analysis of 1991–2006 data found that Indigenous women had, after adjusting for diagnostic period and sociodemographic factors, a risk of death from breast cancer 68% higher than other women with breast cancer (Cancer Australia, 2012). Another recent review also found an overall pattern of poorer breast cancer survival for Indigenous women and variations along the continuum of care (Dasgupta et al, 2017). A study on cancer survival in children found that Indigenous children were 1.6 times as likely to die within 5 years of diagnosis as other children and this remained significant following adjustment for socio-economic status and stage at diagnosis (Valery et al, 2011).

The rate of cancer management among Indigenous patients was slightly lower than that for other Australian patients—21 and 27 per 1,000 GP encounters respectively in 2010–15 (age-adjusted).

Figures

Figure 1.08-1

Proportion of deaths by cancer type, Indigenous Australians, by sex, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT, 2011–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of ABS Mortality Database

Figure 1.08-2

Age-standardised mortality rates, cancer, by Indigenous status, 1998 to 2015

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of ABS Mortality Database

Figure 1.08-3

Age-standardised incidence of bowel and lung cancer by state and territory and Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA and the NT, 2008-2012

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2013

Figure 1.08-4

Age-standardised incidence of breast and cervical cancer in females by state and territory and Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA and the NT, 2008-2012

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2013

Figure 1.08-5

Incidence of digestive system (excluding bowel) and lung cancer (age-specific rates per 100,000 population), by Indigenous status and age, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA and NT combined, 2008-2012

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2013

Figure 1.08-6

Five-year crude survival for selected cancers by Indigenous status and sex, WA Vic, Qld, NSW and the NT, 2004-2012

Source: AIHW Australian Cancer Database 2013

Implications

The lower survival rate for Indigenous Australians from some cancers may be partly explained by factors such as lower likelihood of receiving treatment, later diagnoses, comorbidities, and greater likelihood of being diagnosed with cancers with poorer survival (Cunningham et al, 2008; Supramaniam et al, 2011; Moore et al, 2014; Shahid et al, 2016). Evidence suggests that improvements in cancer care for Indigenous Australians are required; including in cancer diagnosis, treatment, and health support services so they are more accessible and acceptable to Indigenous Australians (Condon et al, 2014; Meiklejohn et al, 2016). The CanDAD project is an approach whereby Aboriginal communities are working with policy makers, service providers and researchers to change the way Indigenous cancer data are collected and utilised (Brown, A et al, 2016).

Cancer Australia aims to minimise the impact of cancer, address disparities and improve outcomes for people affected by cancer. Cancer Australia's work is underpinned by a model for engaging Indigenous communities including: evidence translation, community engagement, collaboration and capacity building, message repetition and sustainability. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework 2015 provides a shared agenda for improving Indigenous cancer outcomes in Australia (Cancer Australia, 2015; Zorbas & Elston, 2016).

The Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP) focuses on the prevention, early detection and management of chronic disease, including cancer. Cancer prevention under the IAHP includes the Tackling Indigenous Smoking Program, which aims to reduce to reduce smoking rates (see measure 2.15). The IAHP also funds the National Bowel Cancer Screening pilot project, which aims to increase bowel cancer screening rates for Indigenous Australians.

The HPV Vaccination Program includes specific communication strategies for Indigenous communities such as distribution of tailored resources to schools, as well as targeted public relations activities and social media engagement. BreastScreen Australia and the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program include culturally specific advertising and stakeholder engagement. State and Territory governments provide a range of programmes. For example, in Victoria, the Strengthening Clinical Care and Pathways project aims to increase cancer treatment in public hospitals.