1.11 Oral Health

Page content

Why is it important?

Oral health refers to the health of tissues of the mouth: muscle, bone, teeth, and gums. The two most frequently occurring oral diseases are tooth decay (termed ‘caries’) and gum (periodontal) disease. If not treated in a timely manner, these can cause discomfort and tooth loss, impacting a person's ability to eat, speak, and socialise without discomfort or embarrassment (Williams, S et al, 2011). Additionally, oral diseases can exacerbate other chronic diseases (Jamieson et al, 2010a) and have been found to be associated with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, stroke and pre-term low birthweight (Williams, S et al, 2011; Roberts-Thomson et al, 2008).

Caries experience is measured by the average number of decayed, missing and filled infant/deciduous or adult/ permanent teeth. The number of teeth with caries reflects untreated dental disease, while the number of missing and filled teeth reflects the history of dental health problems and treatment. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are more likely than other Australians to have multiple caries, have lost all their teeth, and/or to have gum disease (Jamieson et al, 2010b). They are less likely to have received preventative dental care and more likely to have untreated dental disease and be hospitalised for dental conditions (Jamieson et al, 2010a; Kruger & Tennant, 2015).

Tooth decay can largely be prevented by diet (for example reducing intake of processed sugary foods/drinks), fluoridation of water supplies(Lalloo et al, 2015), appropriate use of fluoridated toothpaste, good oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups. The same risk factors apply to periodontal diseases as well as smoking, diabetes, stress, and substance use (particularly inhalant use). Lower levels of education and income and sub-standard living conditions are associated with oral diseases (Lalloo et al, 2016). In addition to oral hygiene and dental care, tooth loss is associated with increased age and trauma (Jamieson et al, 2010a; Williams, S et al, 2011).

Findings

Based on self-reported Social Survey data, 28% of Indigenous children aged less than 15 years had teeth or gum problems in 2014–15. The most common types of problems were with cavities or dental decay (12%), fillings due to dental decay (11%), needing braces/plate/retainer (6%) and having teeth pulled out due to dental decay (5%).

Among Indigenous children with reported teeth or gum problems, 56% experienced the problem/s for at least 12 months. Around 29% had their last dental check less than 3 months ago. Eight per cent of Indigenous children with reported teeth or gum problems had never been to a dentist. In 2014–15, 6% of Indigenous children were reported as needing to go to the dentist in the previous 12 months but didn’t. The main reasons given by parents were cost (28%), followed by waiting time being too long or service not being available at the time required (18%).

Looking at preventative care, in 2014–15, 82% of Indigenous children aged under 15 years reported brushing their teeth daily; almost half (49%) last had a dental consultation within the previous 12 months and 31% reported having never seen a dentist. Of those who saw a dentist, 39% attended a school dental clinic (55% in remote areas), 25% a government dental clinic (including hospital) and 22% a private clinic (including specialists).

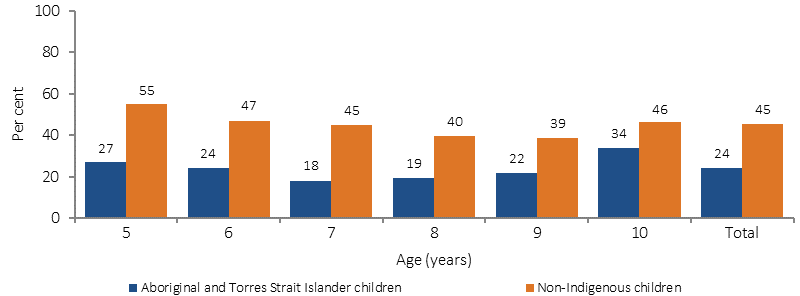

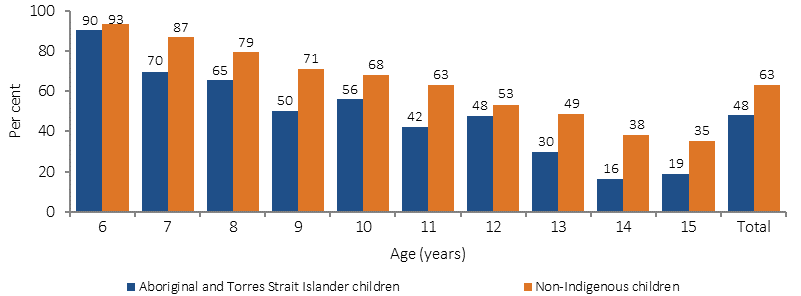

In the 2010 Child Dental Health Survey, for the states with reliable data (Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT), the mean number of decayed or missing teeth among Indigenous children was almost twice that for non-Indigenous children in all age groups. By 14–15 years of age, Indigenous children had, on average, twice as many decayed teeth, 2.8 times the number of missing teeth and more filled teeth than non-Indigenous children. Indigenous children aged 5–10 years were less likely to have no decayed, missing or filled teeth (24%) than non-Indigenous children (45%). For those aged 6–15 years, 48% of Indigenous children had no decayed, missing or filled permanent teeth compared with 63% of non-Indigenous children.

In 2015, nearly 45,400 Indigenous children received dental services under the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (representing 20% of those eligible for these services). In comparison, 35% of eligible non-Indigenous children had received these services.

Between August 2007 and December 2015 more than 25,915 dental services were provided to over 10,939 Indigenous children in the NT under the National Partnership Agreement on Northern Territory Remote Aboriginal Investment (NTRAI), formerly Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory. The proportion of children treated for at least one dental problem was 41%, mostly for untreated tooth decay. Trend data to June 2012 shows that for children who received two or more courses of dental care, there was a 12% decline in the proportion with oral health problems (AIHW, 2012c). The proportion of dental service recipients with experience of tooth decay decreased for most age groups between 2009 and 2015. The greatest decrease was found in those aged 1-3 years old (from 73% to 42%) (AIHW, 2017c).

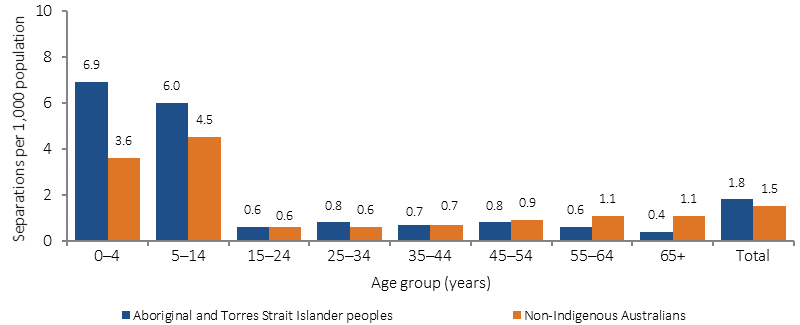

In the two years to June 2015, Indigenous children aged 0–4 years were hospitalised for dental conditions at twice the rate of non-Indigenous children (6.9 per 1,000 compared with 3.6 per 1,000). This indicates poor access to, and a large unmet need for, dental care in this age group. Hospitalisation rates for dental problems declined after 14 years of age. Data on hospital dental procedures involving general anaesthesia show the highest rates were for Indigenous children in the 5–9 years age group (12 per 1,000) followed by 0–4 year-olds (8 per 1,000)—nearly twice the non-Indigenous rate (5 per 1,000). For non-Indigenous Australians, rates were highest for 15–24 year olds (17 per 1,000) compared with 4 per 1,000 for Indigenous Australians in this age group.

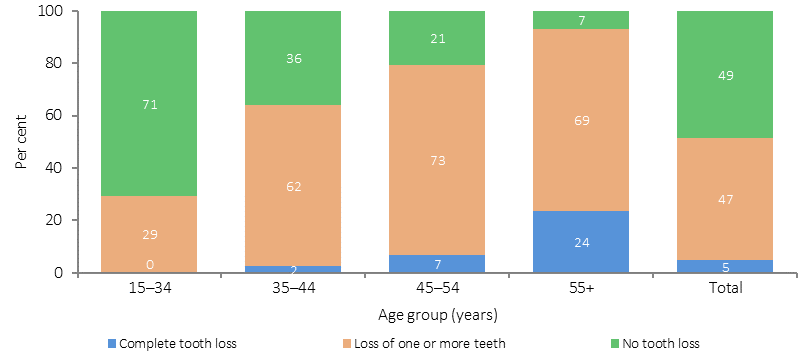

The 2012–13 Health Survey collected data on tooth loss, with 5% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reporting complete tooth loss and a further 47% reporting having lost at least one tooth (excluding wisdom teeth). Rates of complete tooth loss were highest for those aged 55 years and over living in non-remote areas (26%). The proportion was higher for those with: Year 9 or below as the highest Year of schooling (7 times those with Year 12); lowest income (7 times those with the highest income); diabetes (6 times those without); and heart/ circulatory problems (4 times those without).

In 2012–13, of those who had seen a dentist, 33% visited private dentists, 30% a government dental clinic, and 16% a dentist at an Aboriginal Medical Service. Around half (51%) waited less than one week to see a public dentist (non-remote areas). Nearly 14% had never seen a dentist. Nearly half (46%) of Indigenous Australians reported that they brushed their teeth 2 or more times a day and a further 35% reported that they brushed their teeth once a day.

In 2012–13, around 21% of Indigenous Australians reported that they didn’t go to a dentist when they needed to in the previous 12 months. Reasons included: cost (43%), waiting time too long or not available at time required (20%) and disliking professional/feeling embarrassed or afraid (19%).

Figures

Figure 1.11-1

Status of tooth loss by age group, Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over, 2012–13

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of 2012–13 AATSIHS

Figure 1.11-2

Age-specific hospitalisation rates for dental problems, by Indigenous status, Australia, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 1.11-3

Proportion of children aged 5–10 years with no decayed, missing or filled deciduous teeth, by age and Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2010

Source: AIHW analysis of Child Dental Health Survey

Figure 1.11-4

Proportion of children aged 6–15 years with no decayed, missing or filled permanent teeth, by age and Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2010

Source: AIHW analysis of Child Dental Health Survey

Implications

Implications

Available data indicate that dental health is worse for Indigenous Australians than for other Australians, for both children and adults. Barriers to good oral health include cost of services (see measure 3.14), healthy diets on limited budgets (see measure 2.19), attending services for pain not prevention, insufficient education about oral health and preventing disease, public dental services not meeting demand, lack of fluoridation in some water supplies, and cultural competency issues with some service providers (see measure 3.08) (Dyson et al, 2014; Durey et al, 2016; Johnson et al, 2014).

Prevalence estimates for oral health conditions for Indigenous Australians are based on out-of-date and incomplete surveys—further data development is a priority for this performance measure.

Under the National Partnership Agreement on Adult Public Dental Services (2015), states and territories were provided additional funding for adult public dental services for concession card holders.

Funding for oral health in the NT will continue under the NTRAI. The NTRAI aims to provide oral health services for Aboriginal children under 16 years in 75% of communities across the NT, with at least 50% of all services being preventative. The NTRAI also includes workforce training under the Healthy Smiles Oral Health initiative. In addition to the NTRAI, funding is provided through the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP) to support oral health services, health promotion and workforce training in six NT Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations.

Under the former Health and Hospitals Fund, $2.8 million is being provided to the WA Department of Health, to construct a four-chair dental clinic on the grounds of the Narrogin Regional Hospital.

Under the Victorian Government’s Dental Health Program, Indigenous Australians have priority access to dental services delivered through hospitals, clinics and three dental vans that visit Aboriginal communities. Prevention initiatives for high risk groups such as Aboriginal people include Bigger Better Smiles, and Smiles 4 Miles.

The goal of Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives: Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024 is to improve health and wellbeing across the Australian population by improving oral health status and reducing the burden of poor oral health. The Plan identifies Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a priority population and provides strategies to improve oral health outcomes and key performance indicators.