3.07 Selected potentially preventable hospital admissions

Page content

Why is it important?

Analysis of the conditions for which people are admitted to hospital reveals that, in many cases, the hospital admission could have been prevented through timely and effective care outside of hospital (Li, SQ et al, 2009).

Hospitalisations for conditions that can be effectively treated in a non-hospital setting are referred to as ‘potentially preventable admissions’. These include conditions for which hospitalisation could potentially be avoided through effective preventive measures or early diagnosis and treatment in primary health care (Page et al, 2007). The list of conditions for which hospitalisation is potentially preventable is subject to debate (Li, SQ et al, 2009) and is reviewed from time to time in Australia to reflect advances in health care.

Potentially preventable conditions are usually grouped into three categories:

- vaccine-preventable conditions—including invasive pneumococcal disease, influenza, tetanus, measles and others

- potentially preventable acute conditions—including cellulitis (skin infections), urinary tract infection, convulsions/epilepsy, dental conditions, ear nose and throat infections

- potentially preventable chronic conditions—including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes complications, congestive heart failure, angina, asthma, iron deficiency and hypertension.

Systematic differences in hospitalisation rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians could indicate gaps in the provision of population health interventions (such as immunisation), primary care services (such as early interventions to detect and treat chronic disease), and continuing care support (such as care planning for people with chronic illnesses, e.g. congestive heart failure). Higher hospitalisation rates can also reflect appropriate referral mechanisms and access to hospital care. Among Indigenous Australians, there is also a higher prevalence for the underlying diseases, and Indigenous Australians are more likely to live in remote areas where non-hospital alternatives are limited (Gibson & Segal, 2009; Li, SQ et al, 2009).

A recent study of Indigenous residents living in remote NT communities found that those who utilised primary health care at medium/high levels were less likely to be admitted to hospital (and to die) than those in the low utilisation group (Zhao et al, 2014). Higher levels of primary care utilisation for renal disease reduced avoidable hospitalisations by 82–85% and for ischaemic heart disease the reduction was 63–78%.

Findings

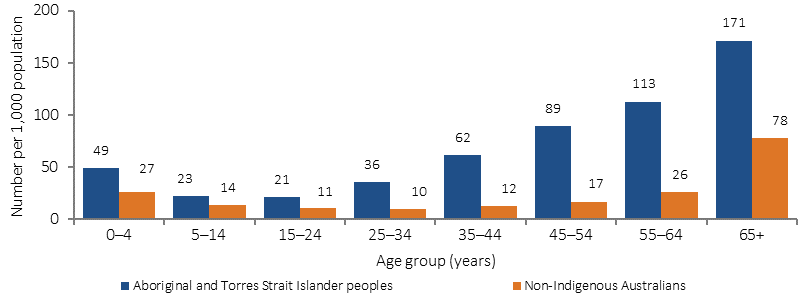

In the two-year period from July 2013 to June 2015, rates for potentially preventable hospital admissions were 3 times as high for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as rates for non-Indigenous Australians. Potentially preventable hospital admissions (excluding those for dialysis) accounted for 15% of all hospital admissions for Indigenous Australians. Differences in hospitalisation rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians were particularly striking for older age groups.

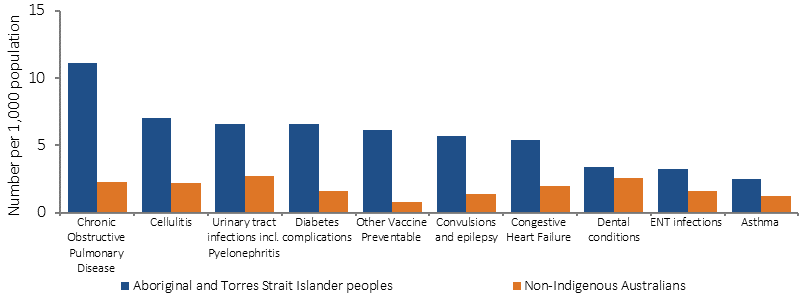

For Indigenous Australians, vaccine-preventable conditions accounted for around 11% of all selected potentially preventable hospital admissions, acute conditions for 51% of admissions and chronic conditions for 40% of admissions. Cellulitis was the leading cause of Indigenous potentially preventable hospitalisations (12%), with rates 3.2 times as high as non-Indigenous Australians. Other significant conditions included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (which had the highest rates after standardising for age), convulsions/epilepsy, urinary tract infections, and diabetes complications. For children, the most common conditions were ear, nose and throat infections and dental conditions, while for adults chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was the most prevalent.

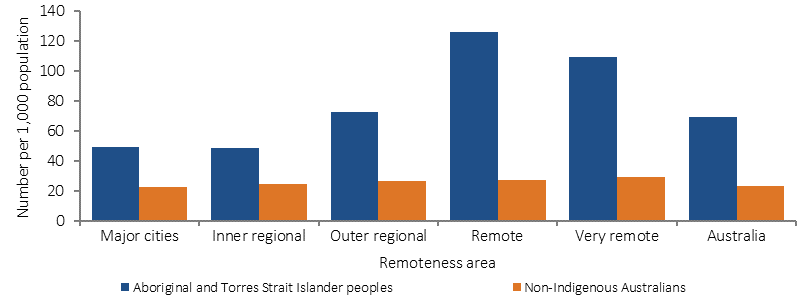

Compared with non-Indigenous Australians, hospitalisation rates for selected potentially preventable conditions were 4.6 times as high for Indigenous Australians living in remote areas, 3.7 times as high in very remote areas, 2.7 times as high in outer regional areas, 2.2 times as high in major cities and 2.0 times as high in inner regional areas. Potentially preventable hospitalisations rates for Indigenous Australians were highest in remote areas (126 per 1,000) and very remote areas (109 per 1,000) and lowest in inner regional areas and major cities (both 49 per 1,000).

Indigenous potentially preventable hospitalisation rates for both chronic and acute conditions have been fairly stable between 2010–11 and 2014–15. Due to changes in coding from 2013–14, time-series data cannot be used for rates of vaccine-preventable hospitalisations under this performance measure (due to an apparent rise in Hepatitis B).

Figures

Figure 3.07-1

Potentially preventable hospital admissions (age-standardised rates), by Indigenous status and remoteness, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW Analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 3.07-2

Potentially preventable hospital admissions, by Indigenous status and age group, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW Analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Figure 3.07-3

Top 10 potentially preventable hospital admissions (age-standardised rates), by Indigenous status, July 2013–June 2015

Source: AIHW Analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

Implications

The most common conditions within the acute group included cellulitis (skin infections); convulsions/epilepsy; urinary tract infections; dental conditions; ear, nose and throat infections. Dental care access issues have been discussed elsewhere in this report (see measures 1.11 and 3.14). The majority of hospitalisations for ear, nose and throat infections occurred in the 0–14 year age group. Rates were 2.5 times the non-Indigenous rate for infants (less than 1 year old) and 1.6 times the non-Indigenous rate for children aged 1–14 years. Analysis of data on ear/hearing problems for this age group found self-reported prevalence rates 2.9 times as high as rates for non-Indigenous children, yet GP consultations are at similar rates (see measure 1.15).

Hospitalisation rates for potentially preventable chronic conditions were 3.2 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians. The major conditions within the chronic group were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes complications, congestive heart failure, and asthma. These high rates reflect the higher rate of chronic conditions in the population and the need to strengthen services that intervene earlier in the disease process, including prevention, early detection, and improved chronic disease management (Li, SQ et al, 2009).

A number of studies have found that improving patient provider communication and collaboration makes it easier for people to navigate, understand and use information and services to take care of their health e.g. matching information to the patient’s needs and abilities, recognising the importance of asking questions, shared decision making, and providing a range of avenues for communication (Øvretveit, 2012; Hernandez et al, 2012).Changes in hospitalisation rates for vaccine-preventable conditions are linked to population immunisation rates (see measure 3.02).

Since 1 July 2014, the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme has aimed to assist in reducing avoidable hospitalisations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by preventing and managing chronic disease and communicable disease through expanded access to and coordination of comprehensive primary health care. Achieving the objectives of this programme will be influenced and supported by the successful implementation of other Indigenous specific initiatives including early childhood reforms, broader health system changes, improvements in identification of Indigenous patients and measures to address the underlying social determinants of poor health.

State and territory governments deliver services and community initiatives for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, designed to encourage healthy lifestyles, prevent chronic disease and improve chronic disease management. These activities are set out in strategic plans with a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, for example the Western Australia Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing Framework 2015–2030 and the ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2016–2020. The ACT plan specifically seeks to improve access to health and health care services. This includes continued support for Winnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Health Service to deliver primary health services, Gugan Gulwan Youth Aboriginal Corporation to provide health and support services for young people and an additional funding commitment in 2016–17 to support additional specialist outreach programs and extension of selected existing programs.