2.20 Breastfeeding practices

Page content

Why is it important?

Breastfeeding is one of the most important human behaviours for the survival, growth, development and health of infants and young children. Early initiation (within the first hour after birth) and exclusive breastfeeding during the first month is associated with a reduced risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality (Khan et al, 2015). Breast milk is uniquely suited to the needs of newborns, providing nutrients readily absorbed by their digestive system and conferring both active and passive immunity. The National Health and Medical Research Council recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and that ideally breastfeeding continue until 12 months of age and beyond if the mother and child wish (NHMRC, 2013b).

Breastfeeding offers protection against many conditions, including sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), diarrhoea, respiratory infections, middle ear infections and the development of diabetes in later life (Annamalay et al, 2012; Horta et al, 2015).

Breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of obesity later in childhood, and also provides health benefits for mothers including reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancer in premenopausal women (NHMRC, 2013b). Breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of otitis media in infants (Bowatte et al, 2015).For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants living in poor housing conditions (see measure 2.02), breastfeeding offers additional protection where hygiene practices required for sterilising bottles may not be easily achieved or maintained.

However, excessive alcohol consumption, substance use or smoking during lactation potentially pose risks to the baby and further research is needed on these relationships (Haastrup et al, 2014).

Findings

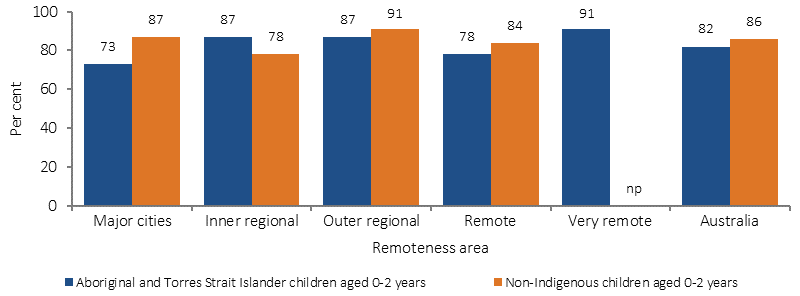

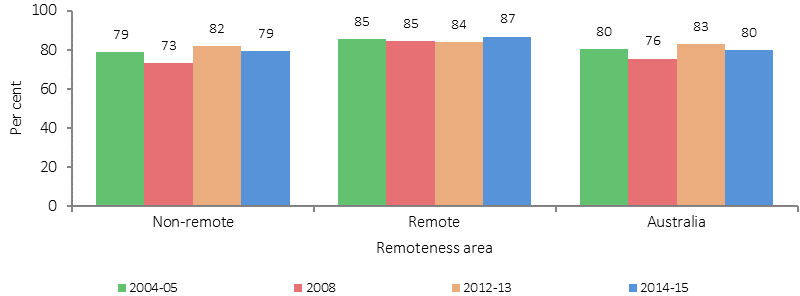

New findings from the 2014–15 Social Survey show that 80% of Indigenous children aged 0–3 years have been breastfed. There has been no significant change in breastfeeding rates for Indigenous children aged 0–3 years between 2004–05 (80%) and 2014–15 (80%). Trends over time in Indigenous breastfeeding rates have ranged from 76% in 2008 to 83% in 2012–13. There is comparable data between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children for those aged 0–2 years. For this age group, 82% of Indigenous children have been breastfed compared with 86% of non-Indigenous children. Indigenous infants aged 0–2 years were 1.2 times as likely as non-Indigenous infants to have never been breastfed (18% compared with 14%).

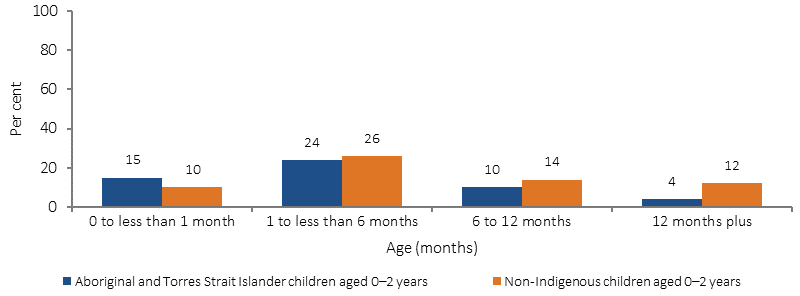

Of those children aged 0–2 years who had been breastfed, Indigenous infants were more likely than non-Indigenous infants to have been breastfed for less than one month (15% compared with 10%). Likewise, Indigenous infants were less likely than non-Indigenous infants to have been breastfed for 12 months or more (4% compared with 12%).

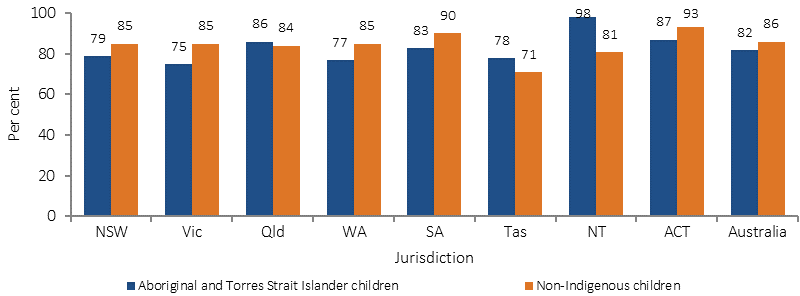

The proportion of Indigenous infants aged 0–2 years who had been breastfed ranged from 98% in the NT to 75% in Victoria. In the NT the Indigenous breastfeeding rate was higher than the non-Indigenous rate (98% compared with 81%).In other jurisdictions the Indigenous rate was similar or lower than the non-Indigenous rate. For example, in Qld the proportion of Indigenous infants who had been breastfed (86%) was on par with the non-Indigenous rate (84%). In major cities, the Indigenous breast feeding rate was 73% compared with 91% in very remote areas.

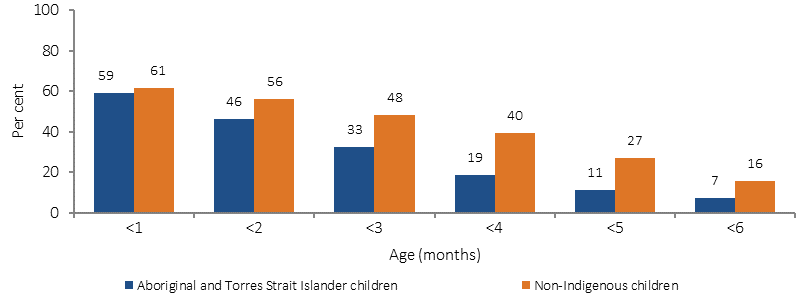

It is not possible to derive exclusive breastfeeding rates from the 2014–15 Social Survey results. In 2010, the Australian National Infant Feeding Survey found comparative rates of exclusive breastfeeding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children aged less than 1 month of age (59% of Indigenous children and 61% of non-Indigenous children). As infants increased in age the proportions of exclusive breastfeeding declined for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, but the Indigenous decline was steeper than the non-Indigenous one. By the recommended age of up to 6 months, only 7% of Indigenous infants were exclusively breastfed compared with 16% of non-Indigenous infants. The Infant Feeding Survey found that almost a third (31%) of Indigenous infants had received soft, semi-solid or solid food by the age of 3 months, compared with 9% of non-Indigenous infants of the same age. By age 5 months similar proportions of Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants had commenced weaning (70%).

For Indigenous infants the main reason given for ceasing breastfeeding was ‘not producing any/adequate milk supply’ (24%), followed by ‘felt it was time’ (17%) and ‘baby not satisfied’ (15%); a non-Indigenous comparison is not available. Maternal and paternal/family smoking is negatively associated with breastfeeding outcomes. Smoking affects the mother’s supply of milk, while exposure to passive smoking is also a factor in reduced duration of exclusive breastfeeding (Baheiraei et al, 2014; NHMRC, 2013b). In the 2014–15 Social Survey, 54% of Indigenous infants aged 0–3 years were living with a current daily smoker and 8% lived in a household with a daily smoker who smoked at home indoors (see measure 2.03).

Figures

Figure 2.20-1

Children aged 0–2 years who were breastfed, by Indigenous status and remoteness, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS, 2014–15 NHS

Figure 2.20-2

Breastfeeding duration for children aged 0–2 years, by Indigenous status, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS, 2014–15 NHS

Figure 2.20-3

Children aged 0–2 years ever breastfed, by state/territory and Indigenous status, 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis 2014–15 NATSISS, 2014–15 NHS

Figure 2.20-4

Exclusive breastfeeding duration to each month of age, by Indigenous status, 2010

Source: 2010 Infant Feeding Survey

Figure 2.20-5

Infants breastfed aged 0-3 years, by remoteness, Indigenous Australians, 2002, 2004-05, 2008, 2012-13 and 2014–15

Source: AIHW and ABS analysis of 2014–15 NATSISS

Implications

Opportunities to promote breastfeeding in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities exist in educational settings and within the health sector, particularly in antenatal and postnatal care. The Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy 2010–2015 was endorsed by Health Ministers in 2009. The strategy aims to protect, promote, support and monitor breastfeeding in Australia, and recognises the importance of breastfeeding support especially for priority groups. The Commonwealth is progressing work for renewing the breastfeeding strategy through the Council of Australian Government’s Health Council.

The strategy recognises the contribution of the New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services initiative for supporting breastfeeding and parenting skills which provides services at 136 sites across the country (see measure 3.01).

The More Targeted Approach campaign is aimed at reducing smoking prevalence among high-risk and hard-to-reach groups. Materials featuring Indigenous women have been included in the Quit For You, Quit For Two component, targeting pregnant women and their partners.

The Department of Health has coordinated the development of National Evidence-Based Antenatal Care Guidelines on behalf of all Australian governments. The Guidelines were developed for health professionals, with input from the Working Group for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Antenatal Care to provide culturally appropriate guidance and information, to provide high-quality, evidence-based maternity care. The Guidelines will be updated by mid-2017.

The Australian Government provides funding for the Australian Breastfeeding Association to support the National Breastfeeding Helpline which offers a free call 24-hour service across all of Australia.

In Tasmania, the Tasmanian Breastfeeding Coalition protects, promotes and supports breastfeeding through actions based on the Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy. The Tasmanian Food and Nutrition Policy remains a relevant framework to guide action and investment for breastfeeding promotion and support.