1.16 Eye health

Page content

Why is it important?

The partial or full loss of vision is the loss of a critical sensory function that has impacts across all dimensions of life. Vision loss and/or eye disease can lead to linguistic, social and learning difficulties and behavioural problems during schooling years, which can then lead to poor education outcomes and employment prospects. Visual impairment can affect health-related quality of life and independent living (West, SK et al, 2002) and the family dynamic (Alshehri, 2016).

Indigenous Australians experience higher rates of cataract, diabetic retinopathy and trachoma compared with non-Indigenous Australians.

Blindness from cataract is now rare due to a highly effective surgical procedure but remains a major cause of vision loss among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Taylor, HR et al, 2015).

Without treatment, diabetic retinopathy can progress to blindness. Although diabetic retinopathy often has no early symptoms, early diagnosis and treatment can prevent up to 98% of vision loss (Taylor, HR et al, 2015). The NHMRC recommends that Indigenous Australians with diabetes should have an eye examination at diagnosis and every year thereafter (Australian Diabetes Society, 2008).

Trachoma in Australia is found almost exclusively in remote and very remote Indigenous populations, with endemic areas in WA, SA and the NT. Trachoma is associated with living in an arid dusty environment; poor waste disposal and high number of flies; lack of hand and face washing; overcrowding and low socio-economic status (NTSRU, 2017). Clean faces have been shown to have a protective effect (Warren & Birrell, 2016), but findings for swimming pools are inconclusive for eye conditions (Hendrickx et al, 2015).

Findings

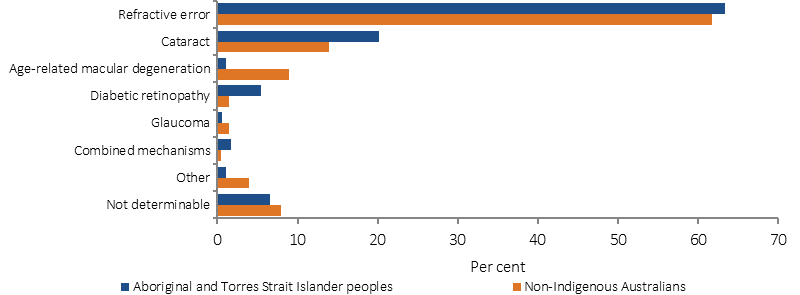

The 2016 National Eye Health Survey (Foreman et al, 2016) measured eye health in Indigenous Australians aged 40 years and over and non-Indigenous Australians aged over 50 years old. This was the first nationwide Australian population based eye health survey which involved clinical examination. In 2016, 11% of Indigenous Australians aged 40 years and over had Vision Impairment (VI) and 0.3% were blind. After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations, the Indigenous rate of VI was 3 times the non-Indigenous rate. The Indigenous rate for blindness was also 3 times the non-Indigenous rate. An estimated 453,000 Australians were living with VI or blindness, including 18,300 Indigenous Australians aged 40 years or older. Of those with VI, the most common cause for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians were uncorrected refractive error, including long and short sightedness (63% and 62%), cataract (20% and 14%), diabetic retinopathy (5.5% and 1.5%), age-related macular degeneration (1% and 9%) and glaucoma (0.6% and 1.5%). The major cause of blindness was cataract (40%) in Indigenous Australians and age-related macular degeneration in non-Indigenous Australians (71%).

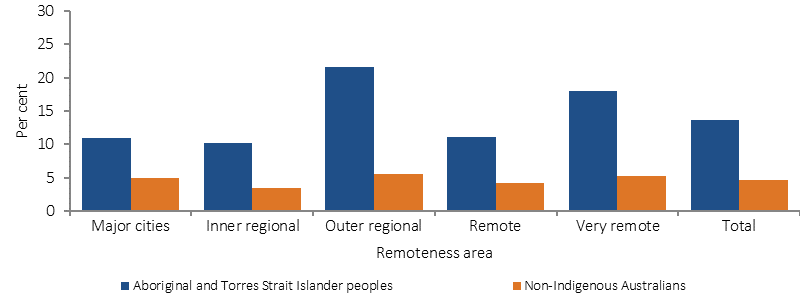

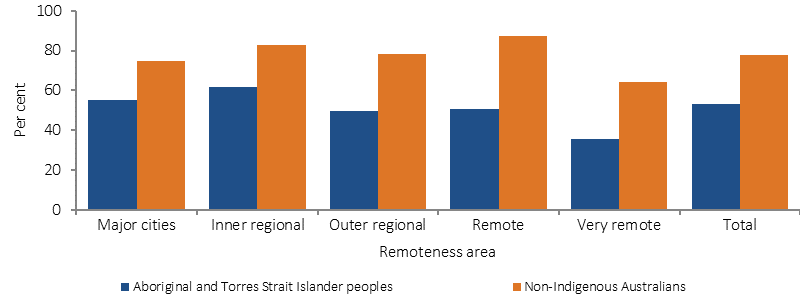

In 2016, the prevalence of VI increased markedly with age in both groups and was almost 2 times higher in 50–59 year old Indigenous Australians and almost 4 times higher in 60–69 year olds compared with non-Indigenous Australians. The Indigenous rate was highest in outer regional areas (17%). For non-Indigenous Australians the rate did not differ significantly by remoteness. Half of those found to have an eye condition were previously undiagnosed (57% for Indigenous Australians and 52% for non-Indigenous Australians). Indigenous Australians with self-reported diabetes had lower rates of recommended diabetes eye checks than non-Indigenous Australians (53% compared with 78%), particularly in very remote areas (35% compared with 64% respectively).

In 2016, for those who needed cataract surgery, Indigenous Australians had a lower coverage rate than non-Indigenous Australians (61% compared with 88%). The treatment rate for refractive error was also lower for Indigenous Australians (83% compared with 94%).

For children the most recent self-reported data on eye health comes from the 2014–15 Social Survey. In 2014–15, 10% of Indigenous children aged 0–14 years were reported to have eye or sight problems, up from 7% in 2008 (ABS, 2016). The main eye or sight problems were long sightedness (5%) and short sightedness (3%). Treatment was received by 89% of Indigenous children with eyesight problems with common treatments including glasses/contact lenses (71%) and eye checks with specialists (27%). A high proportion (90%) of those living in non-remote areas received treatment and 68% received treatment in remote areas.

In the 2012–13 Health Survey across all age groups, one-third (33%) of Indigenous Australians reported eye or sight problems. In 2012–13, 79% of Indigenous Australians with eyesight problems wore glasses/contact lenses.

In 2015–16, around 63,800 Medicare health assessments (which included eye checks) were undertaken with Indigenous children aged 0–14 years, representing around 26% of children in this age group. In 2015–16 there were also around 103,600 health checks undertaken with Indigenous Australians aged 15–54 years and around 29,400 for those aged 55 years and over.

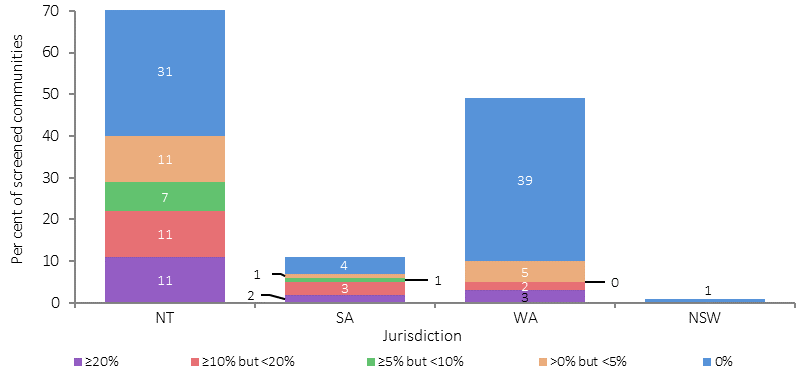

In 2015 the National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit reported the prevalence of active trachoma in children aged 5–9 years was 4.6% in 131 screened at-risk communities (including 67 screened in 2015 and 64 with data carried forward from previous years) in NSW, WA, SA and the NT combined. Prevalence was 7% in SA, 4.8% in the NT, 2.6% in WA and 0% in NSW. Around 30% of communities had endemic trachoma and 57% of communities had no trachoma detected (NTSRU, 2017). Of the cases detected, 99% received treatment in 2015. Health promotion activities were reported in 94 communities. The study also screened for clean faces, with 81% of children overall having clean faces.

Based on GP survey data, eye problems accounted for 1% of all problems managed by GPs at encounters with Indigenous patients during 2010–15. The rate of encounters for total eye problems was similar for Indigenous and other patients. For cataracts, the Indigenous rate was 3.5 times the non-Indigenous rate.

In 2014–15, 68% of Australian Government-funded Indigenous primary health services provided access to optometrists on site and 45% off site, while 35% provided access to ophthalmologists on site and 73% off site.

In the two years to June 2015, there were 6,523 hospitalisations of Indigenous Australians for diseases of the eye (mainly cataracts). The hospitalisation rate was lower for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians (ratio of 0.8). Between 2004–05 and 2014–15, the Indigenous hospitalisation rate for eye disease increased by 160% (from 5.4 per 1,000 to 10.7 per 1,000) in NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined. These rates reflect hospitalisations rather than the extent of the problem in the community.

In 2014–15 the cataract surgery rate for Indigenous Australians was 7.5 per 1,000 compared with 9.0 per 1,000 for other Australians (AIHW, 2016u). In 2015–16, the public hospital median wait time for cataract surgery was 140 days for Indigenous patients compared with 92 days for other patients (the gap has increased by 19 days since 2013–14) (AIHW, 2016x).

Figures

Figure 1.16-1

Main causes of bilateral vision impairment, by Indigenous status, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey, 2016

Figure 1.16-2

Age-standardised bilateral vision impairment by Indigenous status by remoteness, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey, 2016

Figure 1.16-3

Adherence rates to the National Health and Medical Research Council diabetic eye examination guidelines, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey, 2016

Figure 1.16-4

Number of screened at-risk communities(a) according to level of trachoma prevalence in 5–9 year old children, by jurisdiction, 2015

(a) Including 67 communities screened in 2015 and 64 with data carried forward from previous years.

Source: National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit, 2016

Implications

Eye health can be affected by diseases such as diabetes (see measure 1.09) as well as environmental factors linked to higher rates of infection and cross-infection, geographic isolation, economic disadvantage and barriers to health care, which can limit the opportunities for detection and treatment. The 2015 Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision Summary reported that 94% of vision loss in the Indigenous population is preventable or treatable but 35% of Indigenous adults have never had an eye exam (Taylor, HR et al, 2015). A key strategy to close the gap is to ensure those with diabetes undergo annual eye screening, and receive timely treatment (Tapp et al, 2015).

The Australian Government is providing around $51 million over the period 2013–14 to 2018–19 to improve the eye health of Indigenous Australians. Around $16.6 million of this has been allocated to continue national efforts to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem by 2020. Australia is a signatory to the WHO’s Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. The WHO SAFE strategy is being implemented to eliminate trachoma. The Strategy includes surgery (to correct trichiasis), antibiotic treatment, facial cleanliness and environmental improvements (such as fly control, sewerage/rubbish removal, house maintenance). The remaining funding is being used to address a range of activities including improved access to clinical services, streamlining of care pathways, provision of training for health professionals, supply of equipment and trachoma health promotion activities.

Approximately $25.4 million is being provided from 2013–14 to 2016–17 to support the Visiting Optometrists Scheme (VOS), which improves access to optometry services for people living in rural and remote locations. In 2015–16, around 18,979 Indigenous patients (out of 39,112 total including non-Indigenous) were seen through the VOS. The Rural Health Outreach Fund (RHOF) provides outreach initiatives aimed at supporting people living in rural and remote locations to access health care including eye health. In 2015–16, 5,317 Indigenous patients (out of 27,240) were seen by ophthalmologists through the RHOF and a further 3,948 Indigenous patients (out of 9,436) were seen by other eye health professionals.

From November 2016 an MBS rebate will be available for retinal photography screening for patients with diabetes. Indigenous Australians will be eligible for screening annually. To complement this initiative, funding has been provided to purchase retinal cameras and train staff to use the equipment.

There are a range of Indigenous eye health programs delivered by state and territory governments including an Indigenous Diabetes Eye and Screening van in regional QLD, the Outback Vision van in WA and the Collaborative Child Health project in the Pilbara region, WA. Also, the Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation in the NT coordinates eye specialist visits and runs regional clinics (AHAC, 2015). The Victorian Aboriginal Spectacle Subsidy Scheme provided 4,200 spectacles and an increase in eye services in the first 3 years (Napper et al, 2015). For more information, see the Policies and Strategies section.